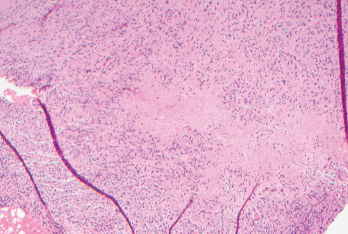

Figure 1. Biopsies of the small bowel mesenteric and serosal nodules demonstrated necrotizing granulomatous inflammation.

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is a common primary immunodeficiency disease, with an estimated incidence of one per 25,000–50,000 individuals.1 The classic presentation includes frequent bacterial infections, secondary to dysfunctional B cell differentiation, impaired immunoglobulin production and diminished antibody response. The clinical presentation may be heterogenous and may include granulomatous disease as an uncommon manifestation. Granulomatous disease has an estimated incidence of 8–22% among CVID patients.2

Here, we describe a patient who presented with small bowel obstruction and was later discovered to have multiple mesenteric and small bowel serosal lesions on exploratory laparoscopy. Biopsies revealed necrotizing granulomas. The patient was eventually diagnosed with CVID following an extensive workup, and his symptoms resolved with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy.

Case Report

A 65-year-old man admitted for abdominal pain with hypotension was found to have small bowel obstruction. Imaging revealed soft tissue density mesenteric masses suspicious for carcinoid tumors. The patient was managed conservatively and was referred to surgical oncology for further evaluation.

The patient had a complex past medical history notable for atrial flutter, for which he underwent cardiac ablation; interstitial lung disease with associated pulmonary nodules, likely secondary to occupational exposure to coal dust and asbestos, as well as smoking; and a pancreatic head mass, which was incidentally discovered on surveillance imaging for his pulmonary nodules. Multiple fine needle aspirations of the pancreatic mass were nondiagnostic, and the mass eventually disappeared on imaging over the course of several months.

The patient underwent exploratory laparoscopy, which showed multiple mesenteric and small bowel serosal lesions. Biopsies of the lesions were negative for malignancy but showed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation (see Figure 1). The patient was subsequently referred to an infectious diseases specialist for further evaluation.

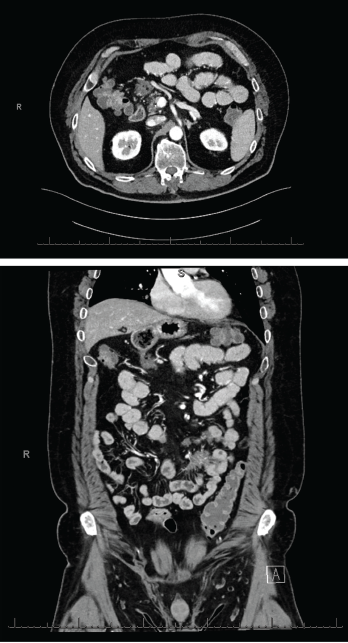

Figures 2 & 3 A CT enterography showed infiltrating soft tissue masses within the mesentery in a predominantly perienteric distribution.

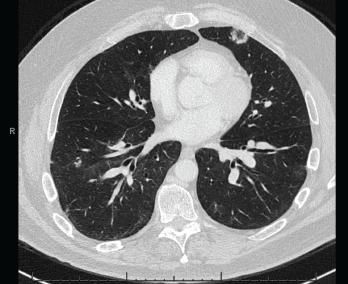

An extensive infectious evaluation was unrevealing (see Table 1). Follow-up computerized tomography (CT) enterography showed similar soft tissue density infiltrating masses within the mesentery (see Figures 2 and 3). A CT scan of the chest showed multifocal, multilobar, subsegmental-sized opacities of unclear etiology (see Figure 4). These findings increased suspicion for an autoimmune etiology of his condition. The patient was referred to a rheumatologist to be evaluated for sarcoidosis, vasculitis and other rheumatic diseases.

At his rheumatology evaluation, the patient noted an unintentional 20 lb. weight loss over the previous year, which had since stabilized, and development of vitiligo. He also described nocturnal wheezing with exertional shortness of breath that had started more than 10 years before; those symptoms were treated with montelukast and a mometasone inhaler without clear benefit. The patient denied eye inflammation, chronic sinusitis, frequent infections, rash or joint pain. The physical exam was notable for vitiligo on his fingers, but was otherwise unremarkable.

The patient did not have anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). Inflammatory markers, angiotensin-converting enzyme and serum IgG4 were within normal limits. Immunoglobulin levels were decreased, with an IgG of 411 mg/dL, IgA of 49 mg/dL and IgM of 10 mg/dL. His CD19 B cell count was low, at 34 cells/μL, and his CD4+ T cell count was also low, at 350 cells/μL (see Table 1). These findings led to the diagnosis of CVID.

The patient was referred to an immunologist and initiated on 500 mg/kg IVIG every two weeks for two doses, followed by 500 mg/kg every four weeks. He was also treated with prophylactic sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim (800 mg and 160 mg, respectively, daily), which was stopped several months into IVIG therapy.

A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis, conducted three months after the patient was started on IVIG, showed resolution of the soft tissue density mesenteric masses. A CT scan of the chest, without contrast, showed a decrease in the multifocal, multilobar opacities, which were thought to represent granulomatous-lymphocytic interstitial lung disease (GLILD) in the setting of CVID.

Ten months following initiation of IVIG, the patient appeared clinically well. However, a repeat CT scan of the chest showed continued pulmonary disease, with interim resolution of several old pulmonary nodules, alongside the development of multiple new nodules. A pulmonary function test showed mild restrictive disease, with decreased diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) compared with 10 months before (forced vital capacity [FVC] 72%, compared with 78%; forced expiratory volume in one second [FEV1] 73%, compared with 79%; FEV1/FVC 75%, compared with 75%; and DLCO 91%, compared with 85%).

The patient underwent a bronchoscopy with endobronchial ultrasound and biopsy, as well as bronchoalveolar lavage. The biopsy showed reactive-appearing lymph node tissue and rare non-necrotizing granulomas. Acid-fast bacilli and Grocott methenamine silver stains were negative for mycobacterial or fungal infections.

The uncommon presentation of granulomatous disease among CVID patients, as well as the consideration of alternative or overlapping infectious, autoimmune or malignant etiologies, poses a diagnostic & treatment challenge.

Figure 4. A CT scan of the chest without contrast showed multifocal, multilobar, subsegmental-sized opacities, which were nodules in some locations and more ill-defined lesions in others.

These findings were felt to be consistent with GLILD. IVIG was continued. Immunosuppression would be considered if the patient became symptomatic or if radiographic disease progressed.

Two years after the diagnosis of CVID, the patient remains clinically well and has not required immunosuppressive agents.

Discussion

Granulomatous disease is a rare manifestation of CVID. Necrotizing granulomatous inflammation is even less common.3–6 Further, clinical presentation with abdominal masses is highly unusual.7 The most commonly involved sites in CVID are the lungs, lymph nodes and spleen.2 The pathogenesis of CVID-associated granulomas remains unclear, although decreased switched memory B cells, increased CD8+ T cells and impaired CD4+ T cell response have been associated with granulomatous disease.2,8

Possible alternative or coexisting diagnoses, including infection, autoimmune disease and malignancy, complicate the diagnosis and treatment of CVID. The presence of concurrent pulmonary and abdominal granulomatous disease with necrotizing granulomas initially raised suspicion for mycobacterial infection, which classically presents with necrotizing granulomas.9

Other bacterial, fungal and viral etiologies, including Bartonella, Brucella, Nocardia, Tropheryma whipplei, Aspergillus, Coccidioides, Cryptococcus, Histoplasma and human immunodeficiency virus, were also considered.9,10 However, the lack of infectious symptoms and the extensive diagnostic evaluation did not support an infectious etiology in our patient.

Among autoimmune diseases, sarcoidosis, vasculitis and connective tissue disease were considered as potential diagnoses. Sarcoidosis affects the lungs and intrathoracic lymph nodes in over 90% of patients, though the disease may manifest in other organs as well. Sarcoidosis classically presents with noncaseating granulomas, along with mediastinal and hilar adenopathy, the latter of which was absent in our patient.11 Elevated angiotensin-converting enzyme level and hypergammaglobulinemia, which are reported with sarcoidosis, were absent as well.12

Table 1: Laboratory Tests

| Test | Result | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| Quantiferon-TB Gold | Negative | Negative |

| Coccidioides antibody, IgG by ELISA | 0.1 | ≤0.9 |

| Coccidioides antibody, IgM by ELISA | 0 | ≤0.9 |

| Coccidioides immitis antibody, precipitin | Negative | Negative |

| Brucella antibody total by agglutination | <1:20 | <1:20 |

| Bartonella species by PCR | Negative | Negative |

| Bartonella henselae antibody, IgG | <1:64 | <1:64 |

| Tropheryma whipplei by PCR | Negative | Negative |

| Histoplasma antigen, serum | Negative | Negative |

| Histoplasma antigen EIA, urine | Negative | Negative |

| Histoplasma mycelia antibody by CF | <1:8 | <1:8 |

| Histoplasma yeast antibody by CF | <1:8 | <1:8 |

| Histoplasma antibody by ID | Negative | Negative |

| Aspergillus galactomannan antigen | Negative | Negative |

| (1,3)-beta-D-glucan | Negative | Negative |

| Cryptococcal antigen, LFA | Negative | Negative |

| Human immunodeficiency virus-1,2 combination antigen/antibody | Negative | Negative |

| Hepatitis C antibody | Negative | Negative |

| C-reactive protein | 0.4 mg/dL | 0.0–0.8 mg/dL |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 1 mm/hr | 0–10 mm/hr |

| Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, IgG | <1:20 | <1:20 |

| Myeloperoxidase antibody, IgG | 0 AU/mL | 0–19 AU/mL |

| Serine proteinase 3 antibody, IgG | 0 AU/mL | 0–19 AU/mL |

| Rheumatoid factor | <10 IU/mL | 0–14 IU/mL |

| Cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, IgG | 2 units | 0–19 units |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme | 30 U/L | 9–67 U/L |

| Serum IgG4 | 4 mg/dL | 1–123 mg/dL |

| CD19 B cell | 34 cells/μL | 74–510 cells/μL |

| CD4+ T cell | 350 cells/μL | 490–1,600 cells/μL |

| CD8+ T cell | 158 cells/μL | 150–1,050 cells/μL |

| Total protein | 6.70 g/dL | 6.00–8.30 g/dL |

| Albumin | 4.40 g/dL | 3.75–5.01 g/dL |

| Alpha-1 globulin | 0.32 g/dL | 0.19–0.46 g/dL |

| Alpha-2 globulin | 0.84 g/dL | 0.48–1.05 g/dL |

| Beta globulin | 0.73 g/dL | 0.48–1.10 g/dL |

| Gamma globulin | 0.42 g/dL | 0.62–1.51 g/dL |

| M-spike | Not observed | Not observed |

| IgG | 411 mg/dL | 768–1,632 mg/dL |

| IgA | 49 mg/dL | 68–498 mg/dL |

| IgM | 10 mg/dL | 35–263 mg/dL |

The presence of pulmonary nodules on imaging and non-necrotizing granulomas on lung lymph node biopsy in the setting of hypogammaglobulinemia pointed toward GLILD instead.13

Further, the lack of characteristic symptoms, along with negative serologies, did not support other autoimmune causes, such as vasculitis (particularly ANCA-associated vasculitis) or other autoimmune diseases, such as associated rheumatoid nodule, granuloma annulare or necrobiosis lipoidica.14

Malignancy was a concern, with lymphoma, carcinoid tumors and metastatic disease of highest suspicion given the initial aggressive manifestation and presence of necrotizing granulomas. CVID patients are also at increased risk for developing malignancy, at an estimated incidence rate of 15%.1 However, the multiple negative biopsy results and marked response to IVIG excluded malignancy as the underlying process.

CVID remains the most likely diagnosis for our patient. Although IVIG is the mainstay of treatment for CVID, no established guidelines exist for the treatment of associated granulomatous disease. IVIG has not demonstrated consistent efficacy in treating granulomatous disease, though this treatment modality did appear to have a significant impact in treating our patient’s abdominal disease.2

Immunosuppressive therapy has shown positive results in treating granulomatous disease, although more investigation is needed. Chief among immunosuppressive agents are corticosteroids. Additional corticosteroid-sparing agents, including cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab and infliximab, are used to avoid prolonged steroid use or to induce complete remission.15–17

Conclusion

The uncommon presentation of granulomatous disease among CVID patients, as well as the consideration of alternative or overlapping infectious, autoimmune or malignant etiologies, poses a diagnostic and treatment challenge. Given the potential for poor outcomes—including infection, unnecessary procedures and progression of disease—with delayed recognition, misdiagnosis or inappropriate treatment, consideration of an immunodeficiency disease is of high importance when approaching a patient with granulomatous disease.

Vania Lin, MD, MPH, is an internal medicine resident at the University of Nevada, Reno, School of Medicine. She plans to pursue a fellowship in rheumatology.

Vania Lin, MD, MPH, is an internal medicine resident at the University of Nevada, Reno, School of Medicine. She plans to pursue a fellowship in rheumatology.

Robert Odrobina, MD, is an assistant professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. His main clinical interests include infections in immunocompromised hosts, especially after bone marrow and solid organ transplantation.

Robert Odrobina, MD, is an assistant professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. His main clinical interests include infections in immunocompromised hosts, especially after bone marrow and solid organ transplantation.

Maria A. Pletneva, MD, PhD, is a gastrointestinal pathologist in the Department of Pathology at the University of Utah.

Maria A. Pletneva, MD, PhD, is a gastrointestinal pathologist in the Department of Pathology at the University of Utah.

Dorota Lebiedz-Odrobina, MD, RhMSUS, is an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine and rheumatology fellowship program director at the University of Utah.

Dorota Lebiedz-Odrobina, MD, RhMSUS, is an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine and rheumatology fellowship program director at the University of Utah.

References

- Tam JS, Routes JM. Common variable immunodeficiency. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2013 Jul-Aug;27(4):260–265.

- Ardeniz O, Cunningham-Rundles C. Granulomatous disease in common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Immunol. 2009 Nov;133(2):198–207.

- Hatab AZ, Ballas ZK. Caseating granulomatous disease in common variable immunodeficiency treated with infliximab. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005 Nov;116(5):1161–1162.

- Pierson JC, Camisa C, Lawlor KB, et al. Cutaneous and visceral granulomas in common variable immunodeficiency. Cutis. 1993 Oct;52(4):221–222.

- Plana Pla A, Bassas-Vila J, Roure S, et al. Necrotizing and sarcoidal granulomas in the skin and synovial membrane, associated with common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015 Jun;40(4):379–382.

- Torrelo A, Mediero IG, Zambrano A. Caseating cutaneous granulomas in a child with common variable immunodeficiency. Pediatr Dermatol. 1995 Jun;12(2):170–173.

- Wang J, Rodriguez-Davalos M, Levi G, et al. Common variable immunodeficiency presenting with a large abdominal mass. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005 Jun;115(6):1318–1320.

- Mechanic LJ, Dikman S, Cunningham-Rundles C. Granulomatous disease in common variable immunodeficiency. Ann Intern Med. 1997 Oct;127(8 Pt 1):613–617.

- Zumla A, James DG. Granulomatous infections: Etiology and classification. Clin Infect Dis. 1996 Jul;23(1):146–158.

- James DG. A clinicopathological classification of granulomatous disorders. Postgrad Med J. 2000 Aug;76(898):457–465.

- Ungprasert P, Ryu JH, Matteson EL. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of sarcoidosis. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2019 Aug 2;3(3):358–375.

- Heinle R, Chang C. Diagnostic criteria for sarcoidosis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014 Apr–May;13(4–5):383–387.

- Rao N, Mackinnon AC, Routes JM. Granulomatous and lymphocytic interstitial lung disease: A spectrum of pulmonary histopathologic lesions in common variable immunodeficiency–histologic and immunohistochemical analyses of 16 cases. Hum Pathol. 2015 Sep;46(9):1306–1314.

- Shah KK, Pritt BS, Alexander MP. Histopathologic review of granulomatous inflammation. J Clin Tuberc Mycobact Dis. 2017 Feb 10;7:1–12.

- Park JH, Levinson AI. Granulomatous-lymphocytic interstitial lung disease (GLILD) in common variable immunodeficiency (CVID). Clin Immunol. 2010 Feb;134(2):97–103.

- Chase NM, Verbsky JW, Hintermeyer MK, et al. Use of combination chemotherapy for treatment of granulomatous and lymphocytic interstitial lung disease (GLILD) in patients with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID). J Clin Immunol. 2013 Jan;33(1):30–39.

- Boursiquot J-N, Gérard L, Malphettes M, et al. Granulomatous disease in CVID: Retrospective analysis of clinical characteristics and treatment efficacy in a cohort of 59 patients. J Clin Immunol. 2013 Jan;33(1):84–95.