In medicine, as in advertising, pictures can be worth a thousand words. From arthritis to vasculitis, imaging studies have been variably employed to aid in the diagnosis, treatment, risk stratification and prognostication of patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal disorders. The same holds true with the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM), in which the clinical utility is high, despite the absence of imaging as a diagnostic variable in the latest European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)/ACR classification criteria.1

In medicine, as in advertising, pictures can be worth a thousand words. From arthritis to vasculitis, imaging studies have been variably employed to aid in the diagnosis, treatment, risk stratification and prognostication of patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal disorders. The same holds true with the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM), in which the clinical utility is high, despite the absence of imaging as a diagnostic variable in the latest European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)/ACR classification criteria.1

These criteria—intended for research classification purposes and not diagnosis—took into account the availability of specific tests, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the gold standard imaging modality for muscle, is not available in all regions. Nevertheless, imaging remains of particular importance in IIM because it provides an assessment of structural abnormalities in muscle tissue, which can help confirm the presence of disease, delineate the type and pattern of its involvement and, ultimately, help guide treatment.

MRI: Myositis Routine Imaging?

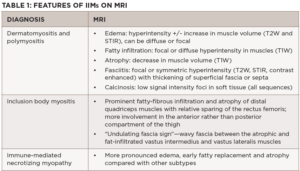

MRI provides excellent soft tissue resolution and contrast, allowing for the evaluation of the extent and distribution of edema, fatty/fibrous replacement and atrophy, and is the main workhorse when it comes to muscle imaging. It is useful for diagnostic purposes to confirm muscle involvement in a patient with suspected disease and can pinpoint potentially high-yield sites for muscle biopsy, albeit not in real time. In some instances, it can help differentiate among the IIM subgroups based on muscles involved and distinguish them from common mimics (see Table 1).

The MRI myositis protocol involves T1-weighted imaging (T1W) and fluid-sensitive T2W with fat suppression or short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequence in the axial and coronal planes.2,3 Gadolinium contrast is not required unless fasciitis, focal myositis or a cystic or solid mass lesion are of primary concern.4 In IIM-affected muscle, T2W and STIR hyperintensities depict edema and increased water content characteristic of active muscle inflammation or necrosis in the acute phase (see Figure 1B). T1W hyperintensities delineate fatty replacement which is a marker of damage and chronicity (see Figure 1A). Calcinosis can be detected on all sequences as signal voids (see Table 1).

A whole-body MRI would be ideal in that it can yield precise patterns of preferential muscle involvement or sparing, making it possible to detect disease-specific muscle signatures or fingerprints. Clinically, however, it is time consuming and cost inefficient. Thus, an MRI of the thigh or of the upper extremity is typically employed, and generally sufficient, for the evaluation of IIMs. In the same vein, while higher magnetic strengths may yield crisper images, the 1.5 Tesla (1.5T) MRI does not appear to fare worse than the 3.0T for the purposes of MSK imaging.5