Every human is a sexual being. Patients need confidence in talking to both their partner and their healthcare provider about sexual concerns. Sexual dysfunction is frequently one of the first manifestations of physical illness, but is often not inquired about on routine review of systems.1 For example, a rheumatology review of systems allows for the unique ability to inquire about potentially sensitive issues such as vaginal dryness or pelvic girdle mobility. Yet sexual concerns are generally overlooked.

Case #1: Martha

As a rheumatology healthcare provider myself, I was caught off guard by a patient. During the end of a routine encounter with a 54-year-old patient with ankylosing spondylitis, Martha said she had one last question.

“I am having trouble opening my legs wide enough to have intercourse with my husband,” she said. Martha admitted that her disease state was affecting her ability to respond sexually and comfortably to her husband in the way to which she was accustomed.

I looked at her quizzically and paused. She said, “Oh, I have embarrassed you, I am sorry.” I looked at her and shook my head, replying, “You didn’t embarrass me; I just don’t know the answer to your problem.”

Over the course of her disease, Martha’s sacroiliac joints had fused. This common phenomenon in ankylosing spondylitis was the root of her problem. Later that week, I spoke to an osteopathic physician from Michigan State University who specialized in osteopathic manipulative medicine (OMM). He agreed to treat her.

At her three-month checkup, Martha had improved her pelvic range of motion and had resumed intercourse with less restriction. She understood that it would require an adherence to exercise and compliance with her medication to maintain her flexibility.

Martha’s dilemma made me wonder how rheumatologic diseases affect intimacy. The more I read, the more I realized that every single chronic illness can change a person’s role in his or her relationship and can, if not treated, adversely affect his or her sexual health. Rheumatology healthcare providers have the unique opportunity to counsel patients who suffer from chronic pain and myriad physical limitations that can have profound effects on intimacy.

It has been estimated that about two-thirds of people with hip osteoarthritis (OA) and a similar number of women with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) experience sexual dysfunction. Nearly one-fifth of respondents to a survey about arthritis and sexuality said they were unable to engage in sexual intercourse due to limitations from arthritis.2

Despite all of this information, many healthcare providers lack the training and self-confidence needed to address their patients’ sexual concerns. A study of orthopedic hip surgeons revealed that 80% reported that they rarely or never discuss sexual activity with their patients.3 Communication is essential to alleviate these issues. The next case study indicates this point.

Case #2: George

George is a 65-year-old retired factory worker who resembles the Marlboro Man. A 40-plus-pack-year smoker, he has both RA and OA and a history of prostate cancer. During a routine visit, I told George about my upcoming lecture for patients about intimacy and arthritis. He nodded in acknowledgment but did not press for more information. I tried again, more directly this time. “Many patients with arthritis have sexual concerns. Are you having any?” He responded without looking at me, “Since my prostate surgery, nothing much worked anymore, so, I just stopped touching my wife.”

Confused, I clarified: “Since your prostate surgery you stopped touching your wife altogether?” “Yep,” he said, “she has been kind of sad about it.”

“You no longer hug or kiss her?” I inquired.

“Why should I? If I hug her or kiss her she will just get excited and then I won’t be able to satisfy her anymore,” George replied.

I looked George in the eye and assured him that was not the case. “Most women like the hugging and kissing better. Everyone needs some type of physical contact to stay healthy,” I said. “That may be all the intimacy Betty needs to be satisfied. Have you talked to her about this?”

I left him with that idea. On his follow-up visits, I continued to keep the lines of communication open. George reported that his relationship has improved with his wife and he is back to showing her affection.

Educating patients on intimacy should include the following:

- The definition of sexuality;

- Physical anatomy;

- Sexual physiology; and

- The fact that sexuality does not necessarily equate to intercourse.

Patients often need reassurance about what should be considered normal when it comes to sexual concerns. In a society where most couples work full- or part-time, children are engaged in multiple activities, and the time that couples spend alone and focused on one another is dwindling, sexual encounters have to be planned. Those who have a chronic illness or disability require even more planning. In the book, The Ultimate Guide to Sex and Disability, the authors discuss the complexities of relationships when one partner is wheelchair bound. The authors describe a patient’s options including having a caregiver prepare them for a sexual encounter versus having their partner get them undressed and positioned. These are real concerns that deserve discussion.

Communication of sexual desires is often difficult even among lifelong partners. A couple married for 10 years fell into the busy norm of family life. With two children under age two and three jobs between them, they were very busy. Nightly, after the kids were in bed and the wife was finally winding down to get some work done, her husband would come in kiss her good night and ask if she was tired. The wife, frequently exhausted from working and being a mom, would reply “yes.” Three months into this nightly ritual the wife realized the question her husband was really asking was whether or not she was interested in sex. Her honest answer sent him out of the bedroom feeling frustrated and her longing for some intimacy. How do I know how this couple felt? That busy mother and wife was me!

After 10 years of marriage, this couple’s communication issue illustrates a lack of a clearly defined ‘mating call.’ I subsequently started to include the idea of the ‘mating call’ in all of my discussions with my patients. Individuals must figure out how they feel most comfortable sending the message (using a mating call) to their spouse that they are still interested in intimacy.

Traci Cox’s book, Supersex for Life, discusses bedroom sabotage and how to maintain intimacy even in longstanding relationships. I have recommended this to couples with great success. Her simplistic, honest approach to rekindling intimacy can serve as a great resource to patients.

Case #3: Ana

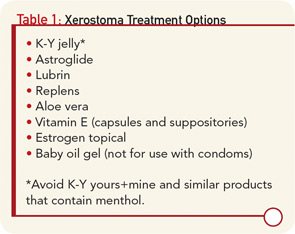

Ana is a 43-year-old patient with Sjogren’s syndrome who reported increasing incontinence, urinary tract infections, and dyspareunia. She had vaginal dryness and was not currently using any estrogen products. We discussed the fact that her lack of estrogen and vaginal atrophy could result in dyspareunia. Ana was given a prescription for an estrogen-containing vaginal cream with instructions to apply a pea-sized amount every other day over the internal labial area. We recommended that she perform a series of Kegel exercises at every stoplight on her way to and from work and before she got into bed at night in order to increase the blood flow to her pelvic floor muscles. We also discussed various lubricants including vitamin E suppositories, Replens, Astroglide, and baby oil gel—assuming that her partner was not using condoms. (See Table 1) Ana was encouraged to avoid any lubricants containing menthol, which could further burn her delicate vaginal tissues. On Ana’s return visit, she reported less dyspareunia and no urinary tract infections.

Fear of pain during intercourse is another common issue that warrants addressing. Pain, concerns of pain, and disease-related fatigue will decrease libido. The partner of the person who has arthritis needs reassurance since he or she may feel more guilt for being responsible for increasing pain during sex. Change in health status of patients may create a change in the role that individual plays at home and can lead to issues with self-esteem and anxiety.2

Anxiety is a universal phenomenon after any change in health status, including myocardial infarction (MI).4 Although the risk of heart attack during sexual activity is quite low, anxiety has been found to be a contributor for an increased risk of repeat MI. In one study, only 4% of patients received sexual guidance from healthcare providers during their hospital stay following an acute MI.3

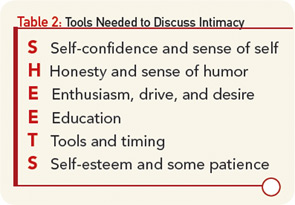

We do our patients a service by asking simple questions such as, “How has your (disease state) affected your sexuality and intimate relationships?” Table 2 (at left) includes the mnemonic and tools that both healthcare providers and patients need to facilitate communication. With consideration and compassion, we can help our patients through this difficult discussion and improve their quality of life.

Iris Zink is a nurse practitioner at the Beals Institute in Lansing, Mich.

Top 10 Myths of Sexuality

Thanks to the constant messages portrayed in the media, many myths about sex exist. These myths often need to be dispelled in order for people to be comfortable and confident in their intimate interactions with their partner. Here are the top 10 myths to consider when addressing intimacy questions with your patients.

- Sex always equals intercourse.

- The goal of sex is orgasm.

- General health does not affect sexual health.

- Use of sexual aids is not sexy.

- Good sex just happens.

- Disabled people are not sexual.

- There comes a time when sex is not important.

- My health and physical changes no longer make me sexy.

- I am who I am sexually because of my parts.

- There is nothing more I could possibly learn about sex.

References

- Clayton A, Ramamurthy S. The impact of physical illness on sexual dysfunction. Adv Psychosom Med. 2008;29:70-88.

- Newman AM. Arthritis and sexuality. Nurs Clin North Am. 2007;42:621-630.

- Rosenbaum TY. Musculoskeletal pain and sexual function in women. J Sex Med. 2010;7:645-653.

- Mosack V, Steinke EE. Trends in sexual concerns after myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009:24:162-170.