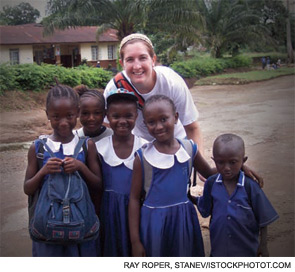

In October 2009, the two of us—an adult rheumatologist and a pediatric rheumatologist, both lupus researchers at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston—embarked on a trip to western Africa. Our initial interest in going to the Republic of Sierra Leone stemmed from research that is currently underway at MUSC involving a special group of people, the African American Gullah community. We wanted to go to the home of the Gullahs in Africa to explore an important issue in the study of lupus—the relationship between genes and environment in pathogenesis. Although our trip made us think differently about lupus, its impact was far greater, giving us a lasting and sobering view of the obstacles of global research and, more importantly, global healthcare. The longer we were there, the more the purpose of the trip changed.

Sierra Leone was a center for transatlantic human trade until 1792, when Freetown, Sierra Leone’s capital, was founded by the Sierra Leone Company as a home for formerly enslaved African Americans. The Gullah people, who currently inhabit the coasts of South Carolina and Georgia, are direct descendents of the slaves who labored on the rice plantations, and their language reflects significant influences from Sierra Leone. The connection between the Gullah people and the people of Sierra Leone is a very special one. The rice plantation zone of coastal South Carolina and Georgia was the only place in the Americas where Sierra Leonean slaves came together in a large enough number and over a long enough period of time to leave a significant linguistic and cultural impact. The people of Sierra Leone look to the Gullah of South Carolina and Georgia as a kindred people sharing many common elements of speech, custom, culture, and cuisine.1

The investigative team at MUSC is currently studying lupus in African Americans from the Sea Island communities of South Carolina and Georgia. The main purpose of the study is to identify and characterize genes as well as factors from the environment that result in the development of systemic lupus erythematosus. The initial findings from the study revealed that lupus in the African American Gullah community is similar in its presentation to that in other African American populations. However, familial prevalence is twice that of other African American cohorts, suggesting a prominent genetic influence on overall disease. In contrast to the situation in the Sea Island communities, lupus is reportedly rare in West Africa where the Gullah originated. The question thus arose as to whether this prevalence gradient results from underdiagnosis of lupus in Africa or the presence of environmental factors in the United States that play a strong role in promoting the expression of this disease. Genetically, the Gullah are very similar to West Africans, with minimal Caucasian or Native American admixture, suggesting that differences in lupus prevalence between the regions is unlikely genetic in origin.

Health Dangers, War Aftereffects

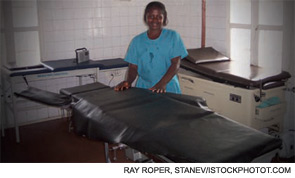

Darius Maggi, MD, a retired obstetrician/gynecologist from Texas, began traveling to Sierra Leone seven years ago to provide medical care to repair obstetric fistulas. He shortly thereafter set up an organization called the West Africa Fistula Foundation that works to improve the lives of women with obstetric fistulas. According to the foundation, in Sierra Leone, one in eight women die during childbirth and, throughout Africa, two to three million women suffer from obstetric fistulas as a result of labor complications. There are very few, if any, Caesarian sections, and many women labor in their villages for days. This situation is improving in most of West Africa, but not in Sierra Leone. Dr. Maggi invited us to travel to Sierra Leone during one of his trips to the region so we could obtain serum and screen for lupus in the Sierra Leonian women seen at the Bo Government Hospital.

Sierra Leone is a country in West Africa similar in size and population to the state of South Carolina. The two largest ethnic groups are the Mende and Temne tribes. English is the official language, and Krio is a language derived from English and several African languages and native to the Sierra Leone people. Krio is widely spoken in all parts of Sierra Leone. Sierra Leone is most widely known in this country for the brutal civil war that began in 1991 and officially ended in 2002, as is depicted in the movie “Blood Diamond,” which took place in Bo. The people of Sierra Leone suffered greatly during this war, which enlisted boy soldiers as combatants and resulted in thousands of deaths and limb mutilations. Each Sierra Leonian has a unique and frightening war story. The war was devastating, especially in Bo.

One of the healthcare providers at the Bo Government Hospital described how he had escaped from the rebels and hid in a church. He proceeded to peek through a window, only to watch his friends and loved ones butchered. The people have never really recovered from the significant devastation that this war caused, which essentially destroyed the country’s entire infrastructure. The region is abundant in natural resources, including oil and diamonds. There is rich soil ripe for growing. Yet, this country continues to fall behind the rest of the world. Though the war has ended, the country continues to suffer from endemic corruption and is the lowest-ranked country on the Human Development Index and the seventh lowest on the Human Poverty Index.2 The life expectancy is 42 years,3 and 30% of children do not live past the age of five.

Desperate Conditions

Once we started our work, we quickly realized that the people of Bo had many more compelling needs than the investigation of whether lupus was present in this region. As we made our way from Freetown to Bo, we found that most of the roads were unpaved and were passable only with a four wheel–drive vehicle. The hospital had a hand-pump well for water, but the water from the well was contaminated. There was no running water in the hospital, and a limited generator supplied electricity a few hours a day. On the pediatric ward, Dr. Ruth saw many children with intestinal perforations from typhoid, and we both saw children die from such infections, because there is no surgeon in Bo. These children would certainly never have died in the United States, where resources are abundant.

Almost all of the adults and children are chronically infected with malaria, and all have parasites. Many children came into the clinic severely anemic from malaria, requiring blood transfusions that had to be provided by family members because there is no blood bank. The hospital has no medicine. If a patient needs medicine, the family has to go to town and buy it. The people, for the most part, do not have any money to pay for medicine. The town of Bo has almost 300,000 people and only three doctors, none of whom are surgeons. The Bo hospital is over 400 beds, with one doctor and three providers with military medic training. The entire country of four million people is served by 30 doctors. There are no medical facilities in the entire country with “modern” diagnostic or surgical equipment. In the vast majority of the country, including Bo, there is no electricity, running water, or sanitation.

Building Hope

We were astounded by the poverty and the lack of basic necessities, such as water, roads, and sanitation. It was difficult to know how to go about helping these genuinely kind people that had already been through so much. To start, we plan to return to Bo with a larger multidimensional medical team in the fall of 2011, and possibly sooner, to help with the installation of a clean water system. We are in the process of funding a water filtration system to put on the well at the Bo Government Hospital to make the water drinkable. Donations to help fund this effort to provide drinkable water for the hospital and surrounding community can be made to Water Missions International (www.watermissions.org), designating your gift to the Bo, Sierra Leone project. Dr. Maggi is in the planning stages of building a hospital in Bo with a modern operating suite. The purpose of this hospital would be to help train Sierra Leonians to take care of their own people. Donations to help Dr. Maggi’s effort in providing care to women with obstetric fistulas can be made to www.westafricafistulafoundation.org.

In summary, the voyage that began as a trip to help answer research questions on lupus became much more. Many living in Sierra Leone live in mud huts or have no shelter, and no one has clean water to drink or to wash in. There are multiple aid organizations in the country doing what they can, but there is no coordination of their efforts. Although vaccines are available for the children through the World Health Organization and the Gates Foundation, the problem is getting them to the children because there is no transportation from the villages to healthcare workers. The people of Sierra Leone do not have the basic human necessities that we take for granted in this country. It is clear that, to improve global research in medicine, we all need to work together to find ways to help these impoverished countries enjoy a brighter future.

Dr. Ruth is assistant professor of pediatrics in the pediatric rheumatology division at the MUSC. Dr. Gilkeson is professor of medicine and microbiology and immunology at the MUSC.

References

- Opala JA. The Gullah: Rice, Slavery and the Sierra Leone-American Connection. 1987. Freetown, Sierra Leone: United States Information Service.

- Tam-Baryoh D. Corruption in Sierra Leone: Who will guard the guards? Worldpress.org. January 15, 2002.

- Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook. Available online at www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html. Updated January 15, 2010. Accessed February 3, 2010.