Preparing to write my final “Rheumination,” I have had the same sense of anxiety, tension, and even dread that TV screenwriters must have felt as they composed the last episode of Cheers, Seinfeld, or Friends. The temptation is great to be memorable but nevertheless stay true to the character of the show. The Rheumatologist (TR) is a limited circulation publication, not a TV franchise, however, and we do not expect a boost in ratings as readers flock to the newsstand to snatch a copy to learn more about my latest meandering—both literal and figurative.

Unlike the anticipated happenings of final episodes of TV shows, for this column there will be no great revelations to keep readers glued to the page and discover some shocking info about past or future. Rest assured, dear reader, when I retire as editor of TR, I will still attend in clinic and run a lab, continuing with gusto and fascination to study what happens when you annihilate Jurkat T cells by necrosis or apoptosis. Just as there is great satisfaction in exploring the life of cells, so there is in exploring the death of cells. After all, life and death go together, just like love and marriage and a horse and carriage. As Frank Sinatra crooned in Sammy Cahn’s memorable lyrics, you can’t have one without the other.

Nevertheless, a last column is a special occasion and I will start by giving thanks (lots of it!) to the leadership of the ACR for giving me the unique opportunity to create a new publication; to a succession of outstanding ACR presidents who recognized the importance of communicating with members and used TR so effectively in their illuminating and informative columns; to the fantastic staff of the ACR who contributed enormously to TR’s success by developing terrific content relevant to today’s rheumatology practice; to the editorial board, who provided insights, encouragement advice, articles, and commentaries; and to the many authors who submitted articles whose quality rivaled—and even surpassed—that of those in top peer-reviewed journals.

I want to especially acknowledge the great team at Wiley that has a love of medical publication and a deep commitment to the highest standards of journalistic excellence. Dawn Antoline, the Wiley editor of TR, is a brilliant editor who is smart and thoughtful and handles a complicated job with great poise and aplomb. The other key member of the TR team is Lil Estep, who is an inspired and visionary art director. I don’t know how she does it, but Lil is a wizard with PhotoShop and has a keen sense of beauty. She is also very funny. As of the writing of this column, I had never met Lil in person, but our conference calls have always been a rollicking good time and one of the high points of my editorship. Often, my goal in suggesting an illustration for an article is to hear Lil shout gleefully, “I love it!” Dawn and Lil have been incredible and I will miss working with such talented and creative people. I have enjoyed every minute of it.

While it is always difficult to leave a venture you helped create, I am happy to turn the editorial duties over to Simon Helfgott, MD, from the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Simon is a very distinguished rheumatologist who is an outstanding scholar. I wish him great success and know that he will do a terrific job.

Windy City Musings

How will I conclude this final installment of the life and times of an academic rheumatologist who searches for fame, fortune, and funding (grants, of course) while traveling the high seas and flying the friendly skies?

If my recollection is correct, the last line of the final episode of Cheers was Sam Malone saying, “Have a good life,” to the departing figure of Diane Chambers as she walked up the stairs of the Boston bar made famous by its joyful but dysfunctional inhabitants. While I could end here with a similar statement, “Have a good practice” simply does not cut it. Such a finale has no pizzazz, no emotional oom-pah-pah.

Since I like to write about my travels, my hope was to describe the ACR meeting in Chicago, since there would much exciting science to recount as well as the exhilaration that always comes when the world’s rheumatologists assemble in America. Unfortunately, in journalism there are deadlines and there is no way that I could write about the meeting in time for the December issue. By circumstance, however, I was in Chicago in early October and I can at least give you my impression of the great city just before winter blasts in.

I went to Chicago for a meeting of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Arthritis, Connective Tissue, and Skin Sciences Study Section, which goes by the abbreviation of ACTS. I try to be a good citizen so, when asked by a program official in the review branch to lend a senior voice to the grants evaluation process, I had a hard time saying no. After all, the NIH has been good to me (not as good as I would have liked) and I have been the principal investigator on RO1, R21, T32, and program project grants. (What do you think I have been doing all these years, writing for GQ?) I therefore signed up for a four-year stint. I actually like reviewing grants, although two days in a dark conference room in a Holiday Inn somewhere in the great wasteland of Montgomery County is not exactly Shangri-La.

I arrived in Chicago on a delightfully cool and crisp Sunday afternoon just as the Monsters of the Midway were bashing heads with the Carolina Panthers out at Soldier Field. After I checked into the hotel, I decided to amble around downtown to take in the sights and sounds and imagine the look of the city when the streets would overflow with rheumatologists instead of Bears fans wearing blue and orange jerseys emblazoned with “Payton 34” and “Urlacher 54.”

I started with a stroll down Michigan Avenue, which is known as the Magnificent Mile and is truly one of great boulevards around, leagues ahead of Ninth Street in Durham (my home town) and a strong rival to New York’s Fifth Avenue. New York and Chicago are different places, however. New York is a great world city while Chicago is a great American city. Michigan Avenue emits a distinct blend of openness, rawness, and rowdiness that is prototypically American, even if it lacks the glamour and sophistication of Fifth Avenue.

My path around the city on that Sunday afternoon was a bit circuitous because I wanted to get a better sense of the real Chicago, and I crisscrossed Michigan Avenue several times. The downtown of Chicago is in transition, and giant high-rise apartment buildings ascend from land that was once the site of department stores and factories. Rents downtown must be absolutely stratospheric, but hey, from the 34th floor, you can look out your window and gaze at the lake shimmering in the glow of the silver-white moon.

While Michigan Avenue has much to justify its moniker as magnificent—Ralph Lauren, Ferragamo, and Niemann Marcus—just off to the side on Wabash and Rush, the mile is less than magnificent. Walking along the street, I saw a tired looking man wearing a black nylon parka and a baseball cap that said Comcast. In one hand he held a cup for money. In the other, he had a sign that said, “I am homeless and have a 6 year old child. Please help.” Attached to the sign was a photo of a child, who looked quite miserable. On Wells Avenue, another man slumped in a wheelchair, his left leg encased in an external fixation device that some orthopedist had dutifully assembled from shiny metal parts.

Big cities always have beggars, panhandlers, and homeless people who populate the same terrain as the high-end stores that feature the latest fashions from Paris and Milan. People from cities usually avoid those asking for money or, eyes averted, quickly pass by even if they could spare a quarter or a dollar (and often a lot more). The culture says to turn a blind eye to street people in need and I have been taught to do that myself.

Sometimes, however, the blind eye sees, and just down from the street from Barneys, I saw a man shuffling slowly along the street, his eyes muddy and dead. My eyes were drawn to his feet, which were bare; he walked on pieces of cardboard secured with twine. The man’s toes were bloody and crusted with scabs. Had he been a patient in the nearby Northwestern Hospital, his ward team would have called in a squadron of consultants, most certainly a rheumatologist who would wonder about vasculitis and recommend an antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody test and maybe an angiogram. The man with the bloody feet was not a patient, however, but just another passerby making his way in the shadow of soaring building of glistening glass and steel.

Pizza and Science

After my walk, I settled in at Lou Malnati’s restaurant, drinking a Stella while I waited for my sausage and pepperoni pizza amidst the roar of the crowd and sonic blasts from the big screen TV, whose vivid colors exploded above the bar like bolts of lightning. The atmosphere was feverish and the room howled with the aroma of hops and spice.

Since a deep-dish pizza takes 30 minutes to bake, I used the time to think about the deliberations of the study section that would take place over the next two days. Sadly, these are the times that try academicians’ souls. Funding rates are likely to be well less than 10% and the pressure on applicants is fierce, necessitating snazzy proposals popping with novelty and glitzy with cutting-edge technology.

“Translation” is the buzz-word now, but giving this pursuit top priority for funding can sometimes be a buzz saw, cutting down imaginative ideas and fundamental discovery research whose connection to disease seems remote at best. At its best, science is about knowledge for its own sake, although good things almost always happen when science is done right. We just can’t predict where those good things will turn up. Lest I remind you, the Nobel Prize for medicine this year was awarded to an investigator, Jules Hoffman, whose discovery of Toll-like receptors came from a study of how fruit flies fend off infection. Who knew flies got disease? I thought flies transmitted disease.

Biology is complicated, however, and not every protein, RNA, or metabolite that shows up as a blip in an “omics” profile will make a good biomarker or target of therapy. There is much randomness, serendipity, and luck in the journey from bench to bedside. Please remember that anti–tumor necrosis factor started out as a drug for sepsis and that allopurinol was invented as a way to increase blood levels of 6-mercaptopurine to treat malignancy. Furthermore, some of the key insights into gout—a common disease of older people—came from the investigations of rare genetic diseases of children. The study of Lesch-Nyhan syndrome helped elucidate purine metabolism while the study of conditions like Muckle-Wells syndrome demonstrated how inflammasome triggering can lead to interleukin (IL)-1 production. Fortunately, for children with autoinflammatory diseases, anikinra (IL-Ra) is available as a treatment; although IL1-Ra was conceived initially as a sepsis drug, it got its first approval for rheumatoid arthritis.

My pizza finally arrived, and this bubbling cauldron of molten mozzarella and tomato embedded with chunks of peppery meat was a culinary hit. Whatever it lacked in finesse, it made up in flavor, and the tiramisu for dessert was quite creditable. After my dinner, I walked back to my hotel. The wind had picked up and the air pulsed with the stroboscope lights of evening traffic and the whoosh and whine of speeding cars. Every so often, in the distance, I could hear a Bears’ fan bellowing still another exultant whoop over the victory on the gridiron. The mood of the city seemed upbeat.

A Somber Note on the Magnificent Mile

On New York’s Fifth Avenue, St. Patrick’s Cathedral stands as a majestic Gothic monument that looks as if it were plucked from Chartres or Beauvais and resettled in Gotham. The Magnificent Mile has no such formidable edifice, but there is jewel of a church—a miniature Gothic—called the Fourth Presbyterian Church right across from the John Hancock Center. I never knew that Presbyterian churches were called something other than the first. Here in Chicago was the fourth. Where are the second and third?

In front of the church there was a small grassy area enclosed by a black wrought-iron fence and shaded by a gracious oak tree, leaves still in place despite swirling winds of autumn. My eyes were immediately drawn to a display in this area. Suspended on grooved and rusted iron rods six or seven feet high, the kind used in construction to reinforce concrete, were tens of tee shirts—pink, grey, red, some striped, many with lettering or logos. At first I thought the tee shirts looked like flags or flowers in bloom, a celebration of some kind, but my impression changed quickly when I read the sign that accompanied the exhibit.

As the sign indicated, the display had 77 tee shirts, one each for the 77 children who were killed in the Chicago school system during the 2010–2011 school year. Under the words “Stop the Violence. Invest in Life.” were the names and ages of each child who died. There were Jesus, Joi, Vincent, Kubira, Darnell, and 72 others. The youngest had been 13. Suddenly, I thought of a horrible scene in which the heads of slain soldiers sit on spikes amidst the desolation of a smoking battlefield.

The world has always been a strange place, uncertain on how to strike the balance between violence and life. For those of us in medicine, however, the value of life is always paramount and that is why it is wonderful calling. When it comes to the individual, we want to invest in life and stop the violence, whether from illness, poverty, or the horrible destruction of shoot-outs in the playgrounds and hallways of inner-city schools. I hope that, when you were in Chicago, you were able to see this moving exhibit and reflect on its powerful message.

A Final Farewell

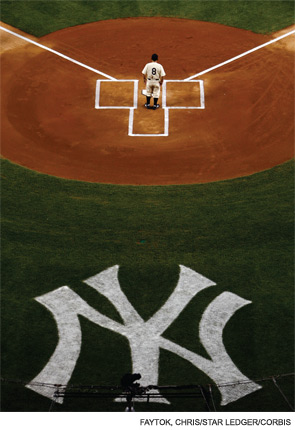

The clock is ticking and it is now time to conclude this “Rheumination.” Not surprisingly, I am again feeling angst as I try to scale the high cliffs of memorable words. Instead of scouring my mind for some profound ideas or bon mots, however, I have decided to fire up Google for help and go to one my favorite places to find wisdom: sports. Being a loyal fan of New York Yankees—despite them breaking my heart by losing to Detroit in Game 5 at the Stadium—I will end this “Rheumination” with a quote from a great philosopher and Hall of Famer from the Bronx Bombers, Yogi Berra. In one of his most famous quotes, Berra said, “You can observe a lot just by watching.”

For five years, I have been watching rheumatology and recording my observations on these pages. I have watched in many places around the world, observed an incredible amount, and had a wonderful time trying to share my experiences with you, my dear readers. To paraphrase another great Yankee who had a bad break in life, I have had a great break in editing TR, and often feel I am the luckiest rheumatologist on earth.

So, dear readers in America and around the world, adios, adjø, au revoir, auf wiedersehen, shalom, sayonara, zai jian, and y’all come down to Durham and see us some time.

Dr. Pisetsky is physician editor of The Rheumatologist and professor of medicine and immunology at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C.