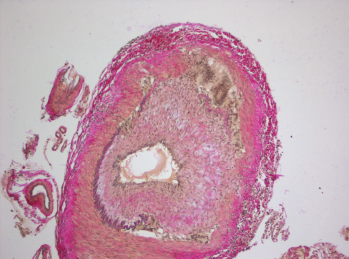

Histopathology of giant cell arteritis in a temporal artery.

wikimedia.org

A recent study, conducted by the Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium and funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), examined whether the addition of abatacept, a drug that affects T cell activation, to standard prednisone treatment could reduce the risk of relapse in patients with giant cell arteritis (GCA).1 Although abatacept has been approved by the FDA to treat rheumatoid and juvenile idiopathic arthritis, there had been no prior experience with its use as a treatment option for GCA.

Carol Langford, MD, MHS, of the Center for Vasculitis Care and Research at Cleveland Clinic, and the study’s lead investigator, discussed the reasons why the study of abatacept was pursued in GCA: “Abatacept inhibits T cell activation, which is thought to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of GCA,” Dr. Langford says. “Because of this mechanism, its favorable safety profile in rheumatoid arthritis and the unmet need for additional treatment options in GCA, abatacept was an interesting drug to investigate.”

Nature & Treatment of GCA

According to Dr. Langford, GCA is an inflammatory disease typically seen in older adults that affects the large blood vessels, leading to a narrowing or blocking of the vessels, which interrupts blood flow. When this affects branches of the internal or external carotid artery, this can manifest with headaches, jaw or tongue claudication, scalp tenderness or cranial ischemic complications, such as vision loss, scalp infarction or strokes.

GCA can also be associated with thoracic aortic aneurysms, according to Dr. Langford, which can occur primarily or as a late manifestation of disease. The condition is commonly associated with polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), an inflammatory disorder that causes aching and stiffness along the shoulder and hip girdle. PMR can occur as an isolated entity or as part of the clinical spectrum of GCA.

Although no uniformly applied treatment protocols exist for GCA, Dr. Langford says an initial dose of prednisone equivalent to 40–60 mg/day is commonly used, with higher doses being considered for cranial ischemic complications.

Glucocorticoids relieve symptoms and, importantly, can prevent blindness, but Dr. Langford says relapses are common in GCA patients, which lead to prolonged glucocorticoid exposure.

“Relapses in GCA are a concern not only because of the potential for disease-related organ damage, but also due to the need for prolonged glucocorticoid treatment,” Dr. Langford says, adding that side effects of glucocorticoids can include infection; osteoporosis; diabetes; cataracts; glaucoma; fluid retention, causing swelling in the lower legs; high blood pressure; problems with mood, memory, behavior and other psychological effects; and weight gain, with fat deposits in the abdomen, the face and the back of the neck.

In one study of 125 patients with GCA, adverse events associated with glucocorticoids were seen in 86% of patients, with two or more events occurring in 58%.2 The development of adverse glucocorticoid side effects was associated with age and higher cumulative glucocorticoid dose.

This is a concern because GCA is a disease of older people. The average age of onset for the disease is 72, and almost all people with the disease are older than 50.3

“Prednisone is effective, but associated with significant potential side effects, and it does not prevent relapses,” says Dr. Langford. “It has, therefore, been a high priority to identify effective therapeutic options that are safer than glucocorticoids to treat GCA.”

Potential to Reduce Relapses

In this randomized and blinded multicenter study, Dr. Langford and her colleagues set out to examine the efficacy and safety of abatacept combined with prednisone compared with prednisone alone for the treatment of GCA.1 The 49 patients enrolled in the clinical trial at 11 academic centers had newly diagnosed or relapsing GCA and were treated with abatacept 10 mg/kg intravenously on Days 1, 15 and 29 and at Week 8, together with prednisone administered daily according to a standardized dosage and tapering schedule. The 41 patients who were in remission at Week 12 were then randomized to continue abatacept or be switched to placebo IV once a month. Prednisone was stopped at Week 28.

At study completion, which was 12 months after the last patient was randomized, 10 patients treated with abatacept had relapsed and 10 stayed in remission, whereas 14 patients randomized to placebo had relapsed, and seven had stayed in remission. The relapse-free survival rate at 12 months was, therefore, 48% for those receiving abatacept and 31% for those receiving placebo (P=0.049). In addition, a longer median duration of remission was seen in those receiving abatacept compared with those receiving placebo (median duration 9.9 months vs. 3.9 months; P=0.023).

Side Effect Risk

Although assessing effectiveness was the primary endpoint of this study, it was not the only outcome that was examined. Dr. Langford says, “Although abatacept had low rate of toxicity in other disease settings, examining safety in GCA was a high priority in this trial.”

There was no difference in the frequency or severity of adverse events between the treatment arms of abatacept and placebo, including the rate of serious adverse events. Infection was of concern, and it was of note that there was no statistically significant difference in the frequency of infections between the two randomized groups.

Study Conclusions

Overall, “patients who achieved remission and were randomized to continue abatacept had a significantly higher rate of relapse-free survival compared with those who were randomized to placebo,” Dr. Langford says. “The difference between groups is clinically meaningful to patients with GCA and corresponds to a prolonged duration of remission, during which time they would not be exposed to glucocorticoids and their potential toxicities that impact quality of life.”

Dr. Langford’s study concluded that in patients with GCA, the addition of abatacept to a treatment regimen with prednisone reduced the risk of relapse and was not associated with a higher rate of toxicity compared with prednisone alone.

Although glucocorticoids remain the foundation of care for GCA, Dr. Langford says that new drugs will change the way GCA is treated in the future. Supporting this viewpoint is that another medication, tocilizumab, was recently approved by the FDA for the treatment of GCA following positive results from Phase 2 and Phase 3 trials.

“These were very encouraging results with the use of abatacept in GCA,” Dr. Langford says. “I would urge rheumatologists to read the full study and to weigh the risks and benefits in deciding whether the use of a novel treatment option combined with prednisone would be appropriate to consider in the setting of their individual patient.”

Linda Childers is a health writer located in the San Francisco Bay Area.

References

- Langford CA, Cuthbertson D, Ytterberg SR, et al. A randomized, double-blind trial of abatacept (CTLA-4Ig) for the treatment of giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Apr;69(4):837–845.

- Proven A, Gabriel SE, Orces C, et al. Glucocorticoid therapy in giant cell arteritis: Duration and adverse outcomes. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2003 Oct 15;49(5):703–708.

- Hellmann DB, Imboden JB. Vasculitis syndromes. In McPhee SJ, Ppadakis MA, Rabow MW, eds. Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment. 50th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2011:818–820.

Note: This project received federal funding from NIAMS, under contract HHSN2682007000036C.