Distinguished Basic Investigator Award

Steven Abramson, MD

Senior Vice President and Vice Dean for Education, Faculty, and Academic Affairs, Professor of Medicine and Pathology, New York University School of Medicine, Director of Rheumatology, NYU-Hospital for Joint Diseases, New York City

Background: A New York City native, Dr. Abramson attended Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., earned his medical degree at Harvard University in Boston, and completed his residency and postdoctoral fellowship at NYU. The bright lights of the big city, a “fascination” with immunology, and a cadre of researchers committed to rheumatology not only piqued his interest, they kept him at NYU for nearly four decades. Internationally recognized for his work in inflammation and antiinflammation, Dr. Abramson’s research currently is focused on mechanisms of inflammation in osteoarthritis, namely inflammatory mediators and novel genes. He is past president of the Osteoarthritis Research Society International, former chairman of the Arthritis Advisory Committee of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and former chair of the ACR’s Drug Safety Committee. He currently is a member of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Skeletal Biology Structure and Regeneration Study Section.

Q: You’ve mentored hundreds of research trainees. What are some of the keys to being a good mentor?

A: You have to understand your role and responsibility when young people come into your division or unit, with regard to the fact that they are in careers that don’t necessarily have a clear and single pathway. … Number two, you have to be excited about the field, and you have to be able to generate that enthusiasm in younger people.

Q: You’ve been involved with the ACR in a variety of volunteer capacities. What has that meant to you professionally and personally?

A: I think the ACR is a great organization. It’s been growing each year. It’s a wonderful way to come together with your colleagues and begin to address important issues in the field, both those affecting physicians and trainees and major questions in science.

Q: You’ve had a front-row seat to the evolution of drug safety in this country. How has drug safety, with respect to rheumatology, evolved in the last 30 years?

A: It certainly has grown up. Things that used to happen locally and required just a handful of people now are happening at a global level. … What we learned was that all drugs have side effects, and some of the drugs with side effects are still very important to treat our patients.

The question is, How do you balance the FDA’s legitimate concerns over safety and the doctors’ concerns over safety?

The doctors are the ones in the offices with the patients who need to benefit from the new drugs. This was part of that era of new drug development.

We not only faced issues of drug safety, but of how the ACR could help to get the voice of the rheumatologist heard.

Distinguished Basic Investigator Award

Gregory Dennis, MD

Senior Director, Medical Affairs, Human Genome Sciences, Inc., Rockville, Md.

Background: Dr. Dennis is a veteran in every sense of the word. A self-described “Army brat” who was raised mostly on Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri’s Ozark Mountains, his internship and residency were done at the Fitzsimmons Army Medical Center in Denver, followed by rheumatology fellowship training at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C., and subsequent stints at the 7th Medical Command in Landstuhl, Germany, and Honduras followed. He rose to chief of rheumatology and rheumatology consultant to the Army Surgeon General before retiring in 2001. With an eye to staying involved in his interest—particularly medical education and the pathogenesis and management of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)—he joined the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) of the NIH. He eventually moved to private industry. “I feel like at this stage of my career I am able to make greater contributions in that regard—considering how we should conduct clinical trials,” Dr. Dennis says. “It’s a good feeling.”

Q: How do awards like this benefit others, not just recipients?

A: While I don’t think anyone will purposely strive to be recognized in this fashion, I do think that many will be motivated to participate knowing that their efforts will be appreciated. They realize that when you volunteer for these activities or make contributions to the field, it will not fall on deaf ears.

Q:What does an award for service, as opposed to research, mean to a veteran clinician?

A: To me, the distinguished service award means you’re being recognized for over and above what you do on a day-to-day basis. Like someone said to me at the ACR meeting, “Wow, you got the good guy award.” I took that to mean that maybe I was the go-to person when someone needs projects worked on or things accomplished. It’s kind of nice.

Q: How do you view the impact you can make from private industry, as opposed to your prior work in the military and with NIH?

A: My ultimate goal is to improve the quality of patients’ lives, and I feel that I’m really able to make a significant contribution to the entire field with the things I have been involved in, whether it be research or collaborating with individuals to conduct quality research. Things I’m involved in right now allow me to facilitate research and medical education to improve patient care on a much larger scale…a guy once told me that, at the NIH, you have a bully pulpit to say, “Here’s how things should be done”…In some ways, being where I am currently allows me to further solidify that bully pulpit.

ACR Excellence in Mentoring Award

Betty Diamond, MD

Head, Center for Autoimmune and Musculoskeletal Disease, Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, North Shore LIJ Health Systems, Manhasset, N.Y.

Background: It’s not often that a top medical award goes to an art history major, but Dr. Diamond has been able to say that a lot. The Harvard Medical School graduate has won a litany of national awards in recent years, including the Klemperer Award from ACR in 2005. The honors reflect a commitment to working with others, including a 20-year stint as director of the Medical Scientists Training Program at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in Bronx, N.Y., and a current post heading the new MD/PhD program at Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine at Hofstra University in Hempstead, N.Y. Still, she says “there’s no such thing as becoming cavalier about an award that is really the work of those one has worked closely with saying they value what you’ve done for them. It’s a different kind of award than any other.”

Q: What is the value of mentoring?

A: Mentoring is critical in one’s life as a scientist, period. I attribute any success I have to great mentors along the way. Mentoring is also critical because everybody needs not just the training, but also the encouragement and the reality check on what they’re doing. To me, it’s a very meaningful award because I think mentoring is so fundamental and so crucial.

Q: In today’s world of tight budgets and increasing demands on one’s time, how does one balance daily duties with mentoring?

A: That’s a hard question and a very reasonable one. But I still think the reason many of us go into this profession is for the gratification that we receive in discovery and in doing research. For the gratification of patient care and thinking about how to improve patient care and sometimes, hopefully, transform patient care. And for the notion that there’s a next generation of investigators and that you can have a profound impact on the life of somebody who is committed to doing the same kind of work and filling the same kind of ecologic niche that you do. It’s a matter of priorities. Everything is stressful and every day is busy. Given those constraints, you choose where to put your efforts.

Q: How does that improve the specialty as a whole?

A: I think it’s pretty obvious that if you put effort into mentoring, it’s like, “Give a man a fish, he has dinner. Teach a man to fish, he has dinner forever.” If you do a good job of mentoring, your own science is better because the people working with you are more rigorous, more creative, and more thoughtful. And the whole field does better.

ACR Distinguished Clinical Investigator Award

Edward Giannini, MSc, DrPH

Professor, Division of Rheumatology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center; Professor of Pediatrics, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio

Background: A Chicago native, Dr. Giannini is a clinical epidemiologist by training. He earned his MSc in immunology from Arizona State University in Tempe, Az., in 1973 and his Doctor of Public Health five years later from the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. His career has always focused on pediatrics, including 30 years as the senior scientist of the Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group. A founding member of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance, he is a well-published author who also served as the principal investigator of the project that led to the discovery of the efficacy of methotrexate in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) and developed the ACR Pediatric 30, a landmark set of criteria adopted in 2002 to help treat JRA.

Q: What about the award means the most to you?

A: Pediatric rheumatology is kind of an orphan disease. Rheumatology itself is an adult specialty, so it has special meaning for someone who has worked in pediatrics his whole life to win this award because you’re winning it in an adult specialty, where you’re competing against very high-power adult rheumatologists. For pediatrics and myself to be recognized, it means that now, toward the end of my career, yeah, what I did really did count for something.

Q: How bad is the staffing deficit for pediatric rheumatology?

A: We even have more of a shortage of pediatric rheumatology scientists. There are very, very few. I was probably one of the first clinical epidemiologists in pediatric rheumatology…it really, since 1976, has come a long way, undoubtedly. Nevertheless, we trail badly the adult rheumatologists in terms of advances in some of our most difficult diseases…It’s extremely important that residents and medical students realize that there is a very dramatic need, not only for clinical pediatric rheumatologists, but people who will go into both laboratory, translational, and clinical research. They’re all interrelated these days.

Q: What does the future hold for pediatric rheumatology?

A: Just as we recognized 20 years ago that there are genes that make you more susceptible to these diseases, we now recognize that there are genes that are going to determine how likely it is that you will respond to a particular agent. If we can look at a kid’s genome and determine if they have genes that make them more likely to respond to particular agents versus some others, or are more likely to have a side effect than others…then we won’t waste time giving expensive drugs that may not work in a kid. We can go right to the ones that his or her genetics suggest are going to work the best.

Henry Kunkel Young Investigator Award

Karen H. Costenbader, MD, MPH

Associate Physician and Co-Director, Lupus Center, Division of Rheumatology, Immunology, and Allergy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston

Background: Dr. Costenbader earned her medical degree from Harvard Medical School, a master’s degree from Cambridge University in England, and a master’s in public health from Harvard School of Public Health. She joined Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) in 2004 and serves as codirector of BWH Lupus Center. A career highlight was when she was awarded the Lupus Foundation of America’s inaugural Mary Betty Stevens Memorial Young Investigator Prize in 2009. Her investigations into risk factors and outcomes have shown that cigarette smoking greatly increases the risk of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and geographic variation in RA incidence.

Q: What is the long-term goal of your research?

A: Understanding the epidemiology of diseases such as lupus and RA, the exposures and risk factors associated with increased disease risk, and how to identify those at the highest risk via specific pathogenic mechanisms, should allow us to intervene and prevent the development of these diseases before they inflict their damage. Wouldn’t that be amazing?

Q: If you were presenting findings of your research, what message would you deliver to rheumatologists about patients who smoke?

A: Rheumatologists, like most physicians, are aware of the long list of deleterious health effects of smoking. They may not be aware that, in addition to cancer and cardiovascular disease, smoking is extremely strongly linked to the risk of RA. The risk of developing RA is highest in those with underlying genetic risk factors and is related to cumulative cigarette exposure, i.e., number of cigarettes smoked per day and number of years of smoking. After about 10 pack-years of smoking, the risk of RA steadily rises, and unfortunately does not come back down for 20 years after smoking cessation. As we also know how addictive cigarettes are and how difficult it is to get long-term smokers to successfully quit, efforts should, in my opinion, be targeted at early smokers and those at risk for RA. Younger people, especially those with a family history of RA or other autoimmune disease, and those with less than 10 pack-years of smoking should really be encouraged to give it up before it is too late. There are also data that smoking cessation does ameliorate existing RA, but preventing its onset in the first place seems more effective.

Q: What does this award mean to you?

A: To have the rheumatology community feel that my research is important is incredibly encouraging. I am so grateful. It is such an honor to join the ranks of my mentors and role models who have received this award before me. Theirs are definitely big shoes to fill, and they have inspired me thus far and continue to do so.

Henry Kunkel Young Investigator Award

Theresa Lu, MD, PhD

Associate Scientist, Autoimmunity and Inflammation Program and Pediatric Rheumatology, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York City, Associate Professor, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York City

Background: Understanding how to manipulate the vasculature in lymph nodes is the basis for Dr. Lu’s research—and one that is paying off after eight years. “We now have some insight into how lymph node vascular growth and function is regulated,” she says. “And, when we disrupt what happens normally to the blood vessels, we can have an impact on immune responses and antibody production. We now need to apply this understanding to ask if disrupting normal vascular regulation can truly be used to manipulate immunity and autoimmunity. We also need to understand whether there is something wrong with vascular regulation or how the vasculature regulates the immune cells in autoimmune diseases.” Dr. Lu earned her medical degree from Yale University and specialized in pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. She had a “fantastic learning experience” working on a Navajo reservation in Arizona before completing a pediatric fellowship at the University of California, San Francisco. The long-term goal of Dr. Lu’s research is to understand the regulation of lymphoid tissue vascular growth and function, and “to use that understanding to disrupt undesired autoimmune responses,” she says.

Q: How excited are you to go to work every day?

A: I’m excited because there are a lot of interesting directions that we can take now. I’m excited to go to work every day because we want to see if the ideas that we are testing are correct; or, if they’re not correct, how we can change the ideas to try and solve this big mystery. … Ultimately we’re excited because we can potentially make a difference in the treatment of rheumatologic diseases.

Q: What did working with the Navajo teach you about medicine and about yourself?

A: I learned to try to consider things from the parents’ perspective. They just sold a silver bracelet to buy enough gas to drive 30 miles and wait four hours to have their four-year-old seen by a pediatrician. Even if it is just a mild viral ear infection that does not require antibiotics, it is important to treat the child and family seriously.

Q: What does this award mean to you?

A: It means a lot to me that my community thinks that my research is meaningful. We are onto a line of research that has the potential to lend insight into disease mechanisms, as well as provide new ideas for therapeutics. I also think that there will be much more to say in the years to come.

ACR Paulding Phelps Award

Gary Bryant, MD, FACP, FACR

Associate Professor of Medicine, Associate Division Director for Clinical Affairs, Division of Rheumatic and Autoimmune Diseases, Vice Chair for Clinical Affairs, Department of Medicine, University of Minnesota Medical School, Executive Medical Director for Medicine Clinics, University of Minnesota Physicians, Minneapolis

Background: Dr. Bryant earned his medical degree from the University of Nebraska in Lincoln and spent the first 22 years of his career as a clinician, researcher, and educator at Gundersen Lutheran in LaCrosse, Wis. In addition to clinical investigations, including phase III trials for new therapies, he developed and supervised quality improvement and efficiency projects aimed at the care processes and appropriate prescribing. He joined the University of Minnesota in 2007 and continued his research on improving patient and physician satisfaction, access, and efficiency. He is a former member of the ACR board of directors, currently serves as chair of RheumPAC, and is the ACR’s delegate to the American Medical Association (AMA). He is the former chair of the Wisconsin Medical Society board of directors. In 2007, Dr. Bryant earned the Wisconsin Medical Society Distinguished Service Award.

Q: What moment(s) stands out the most in regards to your career in research?

A: I thoroughly enjoyed running a site with a very large enrollment in the phase III trials of an experimental Lyme disease vaccine. Although the vaccine did not do well commercially, the basic and translational research significantly added to our knowledge of Lyme disease.

Q: Where do you see quality improvement and patient safety impacting the U.S. healthcare system in the next five to 10 years?

A: The Affordable Care Act, at least as it stands now pending Supreme Court arguments, has ever-expanding accountability for providers, and systems to prove they are providing safe, effective, and efficient care. The system is moving from a pay-for-reporting to incremental pay-for-performance to be phased in by the end of this decade. The ACR has been visionary in its approach to assisting members meet these future requirements through its quality program, including the Rheumatology Clinical Registry.

Q: What advice would you give rheumatologists interested in improving patient safety or physician satisfaction?

A: If you are not measuring something, start. For example, disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. The ACR has tools to assist in this, as well as in all aspects of the challenges facing us in the coming years. You need to measure patient satisfaction with a validated tool in order to see areas that could be targeted to improve.

Q: What does this award mean to you?

A: I am humbled to receive it when I look at the distinguished rheumatologists who preceded me. To be recognized by my professional organization, which I am incredibly proud of, ranks as a highlight of my career.

ACR Distinguished Clinician Scholar Award

Stephen Paget, MD

Physician-in-Chief Emeritus, Professor of Medicine, Hospital for Special Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York

Background: An ACR Master, Dr. Paget is among the veterans of the field. He was physician-in-chief and chair of the division of rheumatology at the Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) and the Joseph P. Routh Professor of Medicine and Rheumatic Disease at Weill for 15 years. He remains as director of HSS’s recently implemented Rheumatology Academy of Medical Educators and is on the board of directors for the hospital’s Lupus Clinical Trials Consortium. He is a member and former co-chair of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) rheumatology subspecialty board. A graduate of Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., he completed his residency in internal medicine at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, was a clinical associate at the Arthritis and Rheumatism Branch of the of NIH, and completed his rheumatology fellowship at HSS, where he has practiced since 1975.

Q: You have referred to the pedagogy of medical school as the weakest leg of academia. Why?

A: In the past, all of us have grown up with this “see one, do one, teach one” concept. It’s basically like being in a craft and you learn, whether it’s making a table or doing a spinal tap. You basically learn from people who learned before…and much of the focus because of funding, reputation, etc., has been on research and clinical work. Now don’t get me wrong, medical schools are wonderful learning environments and they do know how to teach and assess education…But of the doctors that are actually face to face with the medical students, residents, and fellows, few of them really understand what education is all about.

Q: You’re 67 years old and now going for a master’s in public health. Why?

A: Because there are holes in my knowledge base that I want to fill to improve my clinical care, appreciation of the literature, research, and my educational activities. It’s because all through the years, when I’ve done clinical research, I’ve had a clinical epidemiologist/methodologist with me…and while that’s one way of doing it, the fact remains you can become a much better clinical scientist, investigator, even educator, when you have a knowledge base that builds from the bottom up.

Q: What do you think your background shows others?

A: It’s all about lifelong learning…if I can go back to school at 67—and it’s no small thing—anybody can do it. the rheumatologist

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

ACR Presidential Gold Medal Award

William Koopman, MD

Distinguished Professor and Chair Emeritus, Division of Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB)

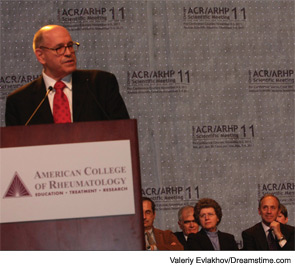

Background: Dr. Koopman earned his medical degree from Harvard Medical School and completed both his internship and residency at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. A three-year stint followed as a staff fellow in the Laboratory of Immunology and Microbiology at the National Institute of Dental Research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). He joined UAB in 1977 and has been affiliated with the university ever since. He was the founding director of the school’s UAB Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases Center and has held three separate endowed chairs during his tenure. His research has focused on regulation of autoantibody expression, particularly rheumatoid factors, and his work has led to 271 original papers, reviews, and book chapters. He has long been an active member of ACR, including a term as the College’s president in 1996–1997. In 2010, he was designated a Master of the ACR. His litany of career awards includes the UAB Distinguished Faculty Award and the President’s Gold Medal (2004) and the Robert H. Williams Distinguished Chair of Medicine Award from the Association of Professors of Medicine (2008). Dr. Koopman was unavailable for an interview with The Rheumatologist. The quotes below are from his award acceptance speech at the 2011 ACR/ARHP Annual Scientific Meeting in Chicago. His speech was a series of “thank yous” to mentors and associates—from a fifth-grade science teacher to his current colleagues whom he said helped shape his career.

On the award itself: “I accept this award humbly and with a great deal of gratitude and a great sense of indebtedness to…a number of giants upon whose shoulders I’ve had the opportunity to stand during the course of my career development.”

On the value of working with other scientists and researchers: “One of the joys of academics is the opportunity to collaborate with colleagues, whether it’s within your institution or outside your institution. I’ve been certainly very blessed in that regard. These collaborations are ones that I look back on with a great sense of joy.”

On a lesson of fortitude provided by former NIH colleague and immunologist Dr. Ann Sandberg: “The first six months, I don’t think I had an experiment that worked. It was pretty devastating. And Ann would continually pat me on the back, and say, ‘Keep at it, keep at it. The experiments will start to work. Try this, try that.’ The lesson of perseverance. And finally experiments did begin to work. I think that it’s a lesson I never forgot…the importance of sticking to something you think is important.”