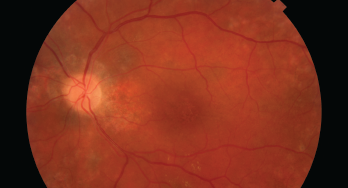

This image shows damage to the retina, which can be caused by HCQ.

Since 1991, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) has been a staple for the treatment of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus; it has been shown to improve survival, reduce cardiovascular risk, thrombosis and renal damage, delay or prevent lupus cerebritis and more. However, HCQ can potentially bind in the retinal pigment epithelium and cause degeneration of photoreceptors, leading to retinopathy.

A recently released statement endorsed by the ACR, the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO), the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and the Rheumatologic Dermatology Society (RDS) underscores points of agreement about the management of HCQ with respect to possible eye toxicity.1 The statement emphasizes the need for effective communication among different specialty physicians and patients to optimize eye safety while ensuring appropriate patients can obtain this important drug.

Background: Perspectives from the AAO

Ocular toxicity from HCQ is of particular concern because it is untreatable, irreversible and progressive if caught at a late stage, even if the drug is stopped.

In 2016, the AAO used new data to update its previous recommendations on screening for chloroquine and HCQ retinopathy.2 Among its key advice was a proposed maximum daily dose of HCQ of no greater than 5.0 mg/kg/day (based on real body weight).

HCQ is packaged as 200 mg pills, and 400 mg per day has been a common dose prescribed by rheumatologists. But under the AAO recommendations, this standard dose was deemed too high for many patients (i.e., a dose of 400 mg per day would be acceptable for an average American man, but too much for the average American woman, based on weight).

Since then, rheumatologists have differed somewhat in their acceptance of these recommendations and have continued to debate the ideal dosing schedule. Some rheumatologists have continued to use doses up to 600 mg per day and/or up to 6.5 mg/kg per day, which was an earlier recommended target dose.3,4 In particular, some have emphasized its critical role for lupus, because HCQ is associated with multiple benefits for patients with this diagnosis.5

This is an issue not just for rheumatologists, but for dermatologists, who have used similar doses of HCQ for multiple applications.

Joint Statement

Ultimately, members of these medical societies agreed to write a shared statement that could be jointly endorsed.1 The working group composing the statement consisted of experts in potential HCQ toxicity: seven rheumatologists, two ophthalmologists and two dermatologists.

Dr. Rosenbaum

James T. Rosenbaum, MD, a professor of ophthalmology, medicine and cell biology and the chair of the Division of Arthritis and Rheumatic Diseases at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, is one author of the recent statement. He contrasts HCQ with a drug like infliximab, whose safety is monitored by the prescribing physician.

“We have a medicine that is incredibly valuable that we’re prescribing. At times, there is a totally different doctor saying, ‘Don’t take this,’” says Dr. Rosenbaum. This can be very frustrating for rheumatologists or other prescribing clinicians.

Rheumatologists, ophthalmologists and other specialists may have differing perspectives on ideal dosing and risk/benefit analysis of HCQ, partly due to some areas of incompleteness in the medical literature. Dr. Rosenbaum points out that we don’t know the minimally effective dosage of HCQ, partly because it is such a slow-acting drug. “We don’t know if, for example, a dose of 200 mg a day would be efficacious for the majority of people,” he says.

Because of this, the study authors did not propose an ideal dosage to manage possible risks and benefits. However, in line with the 2016 AAO recommendations, they note data from the most extensive study on retinopathy in HCQ to date. In this study, an average prescription of 5.0 mg/kg (actual weight) or less per day caused a less than 2% risk of toxicity in patients who had used the drug for up to 10 years.6

Higher daily doses increase the risk to about 10% after 10 years of use, with the risk continuing to rise over time. However, the authors note that for patients who have a normal screening exam, the risk of developing retinopathy in the following year is less than 5%, even in patients who have used the drug for 20 years.6

Overall, the statement authors emphasize the value of HCQ and concur that it can be safely used when given at an appropriate dose and with recommended eye screenings. The statement authors also agree that certain populations warrant special consideration when considering dose and monitoring frequency, for example, patients with reduced renal function.

“The goal of the committee was not to frighten people from using the medicine. The goal of the committee was to make a safe medicine even safer,” notes

Dr. Rosenbaum.

Better Screening Technologies

The study authors underscore the essential role of proper ophthalmological screening in preventing eye complications in all patients.

Dr. Rosenbaum points out that such tools as optical coherence tomography (OCT) and visual fields testing have revolutionized the ability to monitor eye toxicity. OCT provides an incredibly detailed image of the eye, almost as if one were doing a biopsy in living tissue. Dr. Rosenbaum says, “That technology has enabled ophthalmologists to recognize early changes due to [hydroxychloroquine], which otherwise we probably would not have been aware of.” Such tests should be readily available to almost all eye care professionals responsible for HCQ

toxicity screening.

The statement authors recommend such testing within a few months after HCQ is started (to assess for baseline disease, which may complicate later interpretation). They also endorse annual screening, with such tests beginning no more than five years after the drug is started.

The classic description of HCQ retinopathy is of a bull’s eye macular lesion that spares the foveal center, such as might be seen via an ophthalmoscope. However, if patients are regularly monitored with newer screening techniques, such as OCT, damage should be picked up at a much earlier stage, before vision has been affected at all. Adds Dr. Rosenbaum, “If you see something abnormal on the [non-OCT] eye exam, it’s a late finding, and I would almost always recommend stopping the drug.”

In contrast, the authors of the joint statement agree that not all early findings of retinal toxicity via OCT require HCQ be immediately stopped, especially for patients with active rheumatic or dermatologic disease. In cases of definitive and serious retinal damage, cessation is likely warranted. However, borderline cases require more in-depth consideration. With regularly recommended OCT monitoring, many initial eye findings might fall into this category.

Overall, the statement authors emphasize the value of HCQ & concur that it can be safely used when given at an appropriate dose & with recommended eye screenings.

Specialist Input & Patient Desires

Collaboration between patients and subspecialists is key to informed decision making. Notes Dr. Rosenbaum, “The patient should seek input from the ophthalmologist about their risk in terms of future vision and should seek input from the rheumatologist in terms of the value of the medication.”

With that information, the patient can participate in shared decision making about possible decreased dosage and/or increased frequency of eye testing. (Alternatively, more specialized tests, such as autofluorescence, could be performed by a retina specialist.) But it can be challenging to find the best ways to educate patients about risks without unduly dissuading them from a drug that may be valuable for them.

In the real world, Dr. Rosenbaum acknowledges that coordinated care input between healthcare professionals can be a challenge. “I think the biggest issue for all of us is time, and we’re not generally compensated for the time we take trying to find another physician and talk. But another issue is how siloed we’ve become in terms of our expertise and knowledge base.”

Moving Forward

The statement does not speak to other potential toxicities from HCQ, such as cardiac, muscular or dermatologic effects. A second coordinated statement is under review regarding cardiotoxicities relevant to HCQ, some of which gained attention from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Updated information on managing eye toxicities may eventually appear if more becomes known about the drug’s effectiveness at different dosages, if we gain prospective data on toxicity or if we learn more about how blood levels might help effectively manage care.

Rheumatologists should consider lowering doses of HCQ in patients currently taking 400 mg daily if their weight puts the dosage over the AAO recommended amounts (maximum dosage of 5.0 mg/kg/day). Because HCQ is such a long-acting drug, patients could alternate taking daily 400 mg and 200 mg doses to achieve this.4

Dr. Rosenbaum underlines one of the statement’s key points. “It basically says, above all else, we need to do a better job communicating with our colleagues in different subspecialties. And it says that fundamentally the advice offered in 2016 by the American Academy of Ophthalmology remains correct.”

Ruth Jessen Hickman, MD, is a graduate of the Indiana University School of Medicine. She is a freelance medical and science writer living in Bloomington, Ind.

Workgroup members

- James T. Rosenbaum, MD, Departments of Medicine, Ophthalmology, and Cell Biology, Oregon Health & Science University, Legacy Devers Eye Institute, Portland

- Karen H. Costenbader, MA, MD, MPH, Division of Rheumatology, Inflammation, and Immunity, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

- Julianna Desmarais, MD, Department of Medicine, Division of Arthritis and Rheumatic Diseases, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland

- Ellen M. Ginzler, MD, MPH, Division of Rheumatology, State University of New York Downstate Health Sciences University, Brooklyn

- Nicole Fett, MD, MSCE, Department of Dermatology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland

- Susan M. Goodman, MD, Division of Rheumatology, Hospital for Special Surgery, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York City

- James R. O’Dell, MD, Section of Rheumatology, University of Nebraska Medical Center and Omaha VA Hospital, Omaha

- Gabriela Schmajuk, MD, MSc, University of California San Francisco Division of Rheumatology, San Francisco VA Medical Center and Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy, San Francisco

- Victoria P. Werth, MS, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania and Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center, Philadelphia

- Ronald B. Melles, MD, Department of Ophthalmology, Kaiser Permanente, Redwood City, Calif.

- Michael F. Marmor, MD, Department of Ophthalmology, Byers Eye Institute, Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford, Calif.

References

- Rosenbaum JT, Costenbader KH, Desmarais J, et al. ACR, AAD, RDS, and AAO 2020 Joint statement on hydroxychloroquine use with respect to retinal toxicity. Arthritis Rheum. 2021 Feb 9.

- Marmor MF, Kellner U, Lai TY, Melles RB, Mieler WF, for the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Recommendations on screening for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine retinopathy (2016 revision). Ophthalmology. 2016;123(6):1386–1394.

- Winebrake J, Khalili L, Weiner J, et al. Rheumatologists’ perspective on hydroxychloroquine guidelines. Lupus Sci Med. 2020 Nov;7(1):e000427.

- Marmor MF, Carr RE, Easterbrook M, Farjo AA, Mieler WF; American Academy of Ophthalmology. Recommendations on screening for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine retinopathy: A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2002 Jul;109(7):1377–1382.

- Alarcón GS, McGwin G, Bertoli AM, et al. Effect of hydroxychloroquine on the survival of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: data from LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA L). Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(9):1168–1172.

- Melles RB, Marmor MF. The risk of toxic retinopathy in patients on long-term hydroxychloroquine therapy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(12):1453–1460.