In 1982, my wife (also a rheumatologist) and I attended our first American Rheumatism Association (now the ACR) national meeting. After the meeting we stayed with a friend in a suburb of Boston, where we also had the opportunity to meet our hostess’ in-laws, a retired general practitioner and his wife. When her father-in-law shook hands with me, I noticed that he had large, irregular, rock-hard excrescences over his PIPs and DIPs, one of which was draining whitish toothpaste‑like material.

This retired practitioner told me that he had arthritis that often acted up for which he took a well-known brand-name drug (he did not believe in taking generics) for symptomatic relief. When I realized that the drug he was taking was a potent corticosteroid (triamcinolone), I then noticed his rounded face, florid complexion and buffalo hump and understood why he had such trouble getting out of a chair. I told him I thought he had tophaceous gout and that we had better therapies for that than triamcinolone, but he was the seasoned practitioner and did not think that, as a fellow, I could tell him anything he did not already know.

In those pre-Sunshine Act and pre-CLIA days, one of the pharmaceutical companies had given rheumatology fellows polarizing lenses that could be used in a standard microscope to visualize crystals in joint fluid. This rather grouchy (understandable after I squeezed his hand), retired physician told me that the office in the rear of his home was equipped with a microscope, so I offered to show him the crystals.

Off I went with my pharma swag and some of the draining material on a slide to demonstrate negatively birefringent crystals, only to find that the microscope light source was a mirror that reflected light through the objective, an arrangement totally incompatible with the polarizing lenses (two pieces of dark polarized plastic cut from somebody’s broken sunglasses).

Our retired physician was highly amused by my complete failure and took this as further evidence of my youthful inexperience and general ignorance. And now, over 30 years later, I have come to find out that perhaps he was correct in his approach to treating gout.

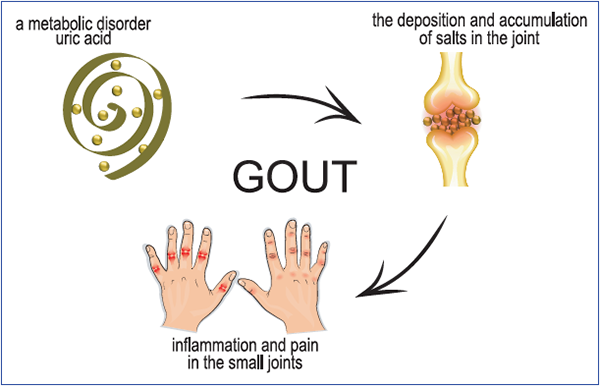

Artemida-psy/shutterstock.com

Treat to Avoid Symptoms

Although rheumatologists have followed a treat-to-target approach in the use of urate-lowering therapy for the treatment and prevention of recurrent gout attacks and tophaceous gout, the American College of Physicians’ (ACP) guidelines now indicate an alternative strategy. The ACP recommends a “treat to avoid symptoms” approach in which urate levels are not monitored.

The literature review cited in the ACP guideline noted that multiple cohort studies reported that patients who did not achieve a serum urate level

Moreover, the ACP doubled down, stating that “even if urate-lowering therapy does reduce gout flares, these studies do not help us understand the tradeoff between the magnitude of benefit and the harms and costs incurred by treatment and monitoring.” The harms and costs of monitoring urate levels are not described, but the potential harms and costs of urate lowering drugs are noted and, for the most part, none of those cited are dose dependent or related to hypouricemia.

On the one hand, the ACP guideline discusses the use of urate-lowering therapies and the relative cost and efficacy of the various drugs used. But if the ACP does not believe that the reduction in the frequency of gout attacks is related to the institution of urate-lowering therapy and reduction of serum urate to a target level, then why would one even begin urate-lowering therapy in the first place? Indeed, the guideline notes that “… the evidence is graded as moderate quality that longer-term urate-lowering therapy (>1 year) reduces gout flares. We consider the magnitude of this reduction uncertain.”

Thus, there is both cost and potential for harm in the use of urate-lowering therapy and little potential benefit, according to the ACP’s analysis. Moreover, as the guideline notes, institution of urate-lowering therapy actually increases the frequency of acute gout flares in the short term, and the guideline recommends concomitant prophylaxis with another drug for eight weeks after instituting urate-lowering therapy, which increases the cost and potential for harm even more. Additionally, some of the placebo-controlled studies cited would suggest that discontinuation of concomitant colchicine at eight weeks leads to a marked increase in acute flares that seemed to recede after six months.

My Questions

So why would anybody start a therapy of uncertain benefit that is well documented (via randomized controlled trials) to increase patient’s symptoms (increased frequency of gout flares)? And how did we get to this point in coming up with our guidelines?

Clearly, randomized, placebo-controlled trials are the gold standard in evaluating therapies, and the evidence provided by these studies is given the greatest weight in developing clinical guidelines. But sometimes other evidence can be quite compelling; nobody has ever tested penicillin against placebo for the treatment of pneumococcal pneumonia, an infection that used to carry a 35% mortality rate. Indeed, the ethics of conducting a placebo-controlled trial of penicillin in the treatment of pneumococcal pneumonia are dicey at best.

We all recognize the shortcomings of uncontrolled and observational studies, but one might have concluded from the similarity of risk reduction with a treat-to-target approach for acute gout flares found in a review of multiple cohort studies, in addition to the results of long-term follow-up studies of controlled trials, that perhaps the risk reduction was real.

Conclusion

So the retired general practitioner with tophaceous gout who made such fun of me for my ignorance and general ineptitude anticipated the recent ACP guidelines for the treatment of gout by nearly 30 years. Corticosteroids provided excellent symptomatic relief for his arthritis flares, a treatment recommended by the ACP, although chronic corticosteroids do not reduce the frequency of gouty attacks and have their own side effects. Our general practitioner had clearly presented the risks and benefits of his approach to therapy to himself, and he was more than willing to make the tradeoff of a puffy face, a buffalo hump and some tophi for the avoidance of potential harm from lowering his serum urate levels, whatever that is.

Clearly, this case is an excellent example of a triumph of the “… strategy of basing treatment intensity on minimizing symptoms.”

Bruce N. Cronstein, MD, is a rheumatologist who received his training at NYU School of Medicine. Currently a member of the ACR Board of Directors, Dr. Cronstein directs the NYU-H+H Clinical and Translational Science Institute at NYU School of Medicine.

Bruce N. Cronstein, MD, is a rheumatologist who received his training at NYU School of Medicine. Currently a member of the ACR Board of Directors, Dr. Cronstein directs the NYU-H+H Clinical and Translational Science Institute at NYU School of Medicine.

Resource

The ACP guideline can be found here.

Disclosures: Dr. Cronstein has acted as a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb and AstraZeneca; he has received grants from AstraZeneca, Celgene and Takeda and has equity in Can-Fite Biopharma. M.S. Dr. Cronstein’s research has been supported by the NIH (ROl AR056672-07, ROl AR068593-02, 1UL1TR001445-02), Arthritis Foundation and Celgene. Dr. Cronstein is the holder of multiple patents.