The ACR recently released an update on the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis.1 The guideline, which includes information on the new therapies abaloparatide and romosozumab, emphasizes the importance of shared decision making by patients and clinicians, and also gives information on the importance of sequential therapy after stopping certain osteoporotic prevention therapies.

The ACR recently released an update on the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis.1 The guideline, which includes information on the new therapies abaloparatide and romosozumab, emphasizes the importance of shared decision making by patients and clinicians, and also gives information on the importance of sequential therapy after stopping certain osteoporotic prevention therapies.

Fracture Prevention

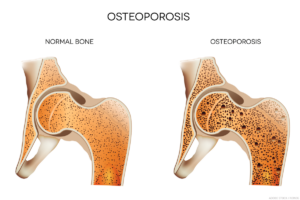

Despite efforts to reduce or eliminate glucocorticoid therapy, many patients with rheumatic or other diseases require treatment over the long term. Yet glucocorticoids increase the risk of bone fractures, especially vertebral fractures, with patients taking higher doses of glucocorticoids and/or longer duration of therapy carrying the greatest fracture risk.

Mary Beth Humphrey, MD, PhD, co-principal investigator of the guideline, professor of medicine and chief of the Rheumatology, Immunology and Allergy Section, the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, notes that common fractures, such as those of the wrist or hip, can prevent patients from performing their regular activities of daily living, and mortality rates after a hip fracture may approach 25% in the following year.2

The other co-principal investigator of the guideline is Linda Russell, MD, director of the Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Health Center for the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York City. She notes that, for many years after the discovery of corticosteroids, no medical society took ownership of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. But in 1996, the ACR released its first clinical guideline to help rheumatologists and physicians in other specialties manage glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis.3 The ACR updated these guidelines several times, most recently in 2017.4

Like other recent ACR guidelines, these employ the GRADE methodology (i.e., Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation). After considering a comprehensive review of the medical literature on this topic, a voting panel made strong or conditional recommendations on specific management questions based on the PICO framework (i.e., Patient/Intervention/Comparator/Outcomes).

The following is a discussion of some of the key areas of interest addressed in the new glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis guideline. For more detail and context, and for information about additional key topics, such as osteoporotic treatment in special populations (e.g., children, patients with kidney transplant, people who may become pregnant and patients receiving very high-dose glucocorticoids), refer to the full guideline.1

Prevention Approaches

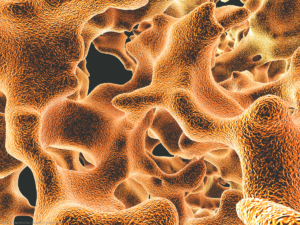

Multiple agents are now available for the treatment of osteoporosis and, specifically, for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. The first agents specifically developed for osteoporosis were bisphosphonates, approved by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) in 1995. These anti-resorptive agents are available in multiple formulations, including in combination with vitamin D and as intravenous (IV) injections, although these carry a slightly higher risk profile than oral formulations.5

The first anabolic treatment agent approved for osteoporosis was teriparatide. The parathyroid hormone recombinant analog mimics the normal physiological actions of parathyroid hormone to stimulate new bone formation.5 Parathyroid hormone-related protein is a structurally similar protein; since the ACR’s 2017 guideline, its analog, abaloparatide, has become available. Both are expensive and require daily injections, which some patients may find burdensome.

The first biologic agent approved to treat osteoporosis, denosumab, inhibits the transmembrane protein and secreted protein receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β ligand (RANKL), which is required for the formation and survival of bone resorptive cells. A newer biologic agent, romosozumab, inhibits sclerostin, a protein released by osteocytes to reduce bone formation. Both are also much more expensive than bisphosphonates.

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), such as raloxifene, originally developed to treat breast cancer, can also work as anti-resorptive agents via their action on bone cells.

Lifestyle Interventions

Lifestyle interventions are a key part of treatment for all patients with potential glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Dr.Russell notes that tobacco and alcohol are both toxic to osteoblasts, so it’s important to provide tobacco cessation support and educate patients to use alcohol moderately.

Dr. Russell

Dr. Russell adds that, when appropriate, stopping or replacing medications that can be detrimental to bone can be helpful, such as replacing a proton pump inhibitor with a histamine-2 receptor blocker. “We also like to promote a robust weight-bearing program, whether it’s brisk walking or using the elliptical or light weights,” she adds.

It’s recommended that all patients on chronic glucocorticoid therapy (i.e., for three months or longer) adopt these lifestyle recommendations. Additionally, patients may need supplemental calcium and vitamin D to achieve optimal levels of these vitamins and minerals so critical for bone health.

Treatment

The 2017 guideline, which only considered fracture reduction as an indication of efficacy, recommended an oral bisphosphonate over other treatment options for patients over age 40 at moderate or high fracture risk, due to the drugs established safety, low cost and the lack of evidence that other agents provided better fracture reduction. Intravenous bisphosphonates, teriparatide, denosumab and raloxifene were recommended next, in that specific order.4

In the updated guideline, oral bisphosphonates are strongly recommended over no treatment in adults aged 40 or older at high or very high risk of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporotic fracture, based on strong data for efficacy and safety in this specific population.

However, the guideline now conditionally recommends parathyroid hormone-based agents over both bisphosphonates or denosumab for adults with very high risk of fracture. This is partly based on a head-to-head study of teriparatide and alendronate, which found that teriparatide increased lumbar and hip bone mineral density and decreased vertebral, but not non-vertebral, fractures at 36 months in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis.6 For adults at high risk of fracture, parathyroid hormone-based treatments or denosumab are conditionally recommended over bisphosphonates.

In contrast, for adults at moderate risk of fracture, the conditional recommendation is for oral or intravenous bisphosphonates, parathyroid hormone-based treatments or denosumab. Pharmacologic treatment is not recommended for low-risk patients taking glucocorticoids.

The guideline also conditionally recommends against both romosozumab and raloxifene, except in high or very high-risk patients who don’t tolerate other anti-osteoporotic agents. This recommendation is rooted in the uncertain safety profiles of these agents with respect to cardiovascular dangers.

Dr. Humphrey points out that because of SERMs’ potential to protect against breast cancer, they can be helpful agents for some women with a high breast cancer risk who also need osteoporotic protection. “But there is also an increased risk of stroke and heart attack from these agents that became more apparent in the last few years,” she adds. “So you really have to do a careful risk assessment.”

Dr. Humphrey

Dr. Russell underscores that when choosing an initial medication for a patient, one should factor in the patient’s comorbidities. For example, an oral bisphosphonate might not be appropriate for a patient with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease, since acid reflux is one of the most common side effects of these drugs. Other patient preference factors, such as willingness to take a daily injection, e.g., for teriparatide, must also be considered.

However, Dr. Humphrey points out that, on a practical level, many patients may not be able to get coverage for certain osteoporosis medications, at least not initially, due to cost differences. “Many of the insurance companies have been holding back on covering teriparatide, abaloparatide, romosozumab and sometimes even denosumab, except for people with really severe osteoporosis, people who have had a prior fractures or people who have failed these other drugs,” she notes.

To date, neither abaloparatide nor romosozumab have achieved FDA approval for people with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis, which may also affect insurance coverage.

Sequential Therapy

When talking with patients about their initial choice for osteoporotic prevention, Dr. Humphrey believes it is also important to talk about the eventual need for sequential therapy, which might influence the treatment preference. New recommendations about sequential therapy were a key addition to the updated glucocorticoidinduced osteoporosis guideline.

“The bisphosphonates stay in your system for a long time,” Dr. Russell explains, “so when you choose to stop those medications, fracture protection continues for up to five years. But denosumab has a different mechanism of action, and it’s in your system for approximately six months. If you don’t follow up with another medication that slows bone loss, like [alendronate] or [risedronate], there can be rapid bone loss.”

According to Dr. Humphrey, we’ve been learning about this risk for the last several years, first for denosumab, but also for other agents like parathyroid hormone-based compounds and romosozumab. The risks of suddenly discontinuing these agents became very clear during the COVID-19 crisis. “If patients didn’t reschedule their denosumab and missed a dose, in that next six months they were starting to have multiple vertebral fractures,” she says.

In the current guideline, it’s strongly recommended that patients who have stopped taking glucocorticoids and are now at low risk for fracture discontinue their osteoporosis therapy. Patients discontinuing bisphosphonates or raloxifene do not need to take an additional osteoporotic prevention therapy. However, to prevent sudden bone loss and vertebral fractures, sequential therapy is strongly recommended for patients stopping parathyroid hormone-based treatments, denosumab or romosozumab.

This follow-up therapy could consist of an oral or IV bisphosphonate. At this time, we don’t know the precise timing to start anti-resorptive therapy or how long this transitional bisphosphonate therapy needs to continue, although we know that a year of therapy gives at least partial protection.7

Although serious complications of bisphosphonates, such as osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femur fractures, are quite rare, Dr. Humphrey points out they have received a lot of press attention. Some patients may be predisposed against bisphosphonates, even though some other treatment options (i.e., denosumab and romosozumab) share these rare risks. Patients need to know at the outset that even if they opt for another initial choice of therapy, they will likely eventually need to take a year of bisphosphonates to stabilize the newly formed bone and prevent vertebral fractures.

Importance of Screening

Before appropriate patients receive any treatment, they must be properly identified, which is why screening is so key. Unfortunately, the number of patients with osteoporotic fractures has increased in recent years, after a decade or so of decline, and many patients with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis are neither screened nor treated.

Dr. Humphrey points out that with the decrease in Medicare reimbursement rates for bone density scans, the number being performed has dropped significantly. She speculates that these increasing rates may have also been partially due to the discovery that some patients could safely take drug holidays from bisphosphonates; however, some patients on such holidays may not have re-initiated needed treatment after five years.

Clinicians can assess patients’ risk through use of calculators, such as the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX), which estimates patients’ 10-year risk of major hip fractures and major osteoporotic fractures more generally, based on features such as sex, body mass index, parental hip fracture, smoking, alcohol intake and other causes of secondary osteoporosis.8

However, patients should ideally receive bone mineral density testing in addition to a test such as FRAX, so clinicians have more complete information to weigh the risk of fracture against the risks of osteoporotic prevention therapy. The guideline also underscores the fact that FRAX alone is not reliable for assessing osteoporotic fracture risk in patients under 40, so bone mineral density testing is especially important for these patients.

“The most important message is that if you are putting someone on longterm glucocorticoid therapy, you should definitely assess their fracture risk,” Dr. Russell says. “It doesn’t mean that everybody needs a medication, but you should make the assessment.”

Even after an initial assessment, patients at moderate to high risk who opt not to start therapy should be reassessed frequently. Dr. Russell points out that even for patients who have never taken glucocorticoids, clinicians need to periodically assess bone health in at-risk patients, such as postmenopausal women.

“My takeaway from this guideline is that we really want people to be treated—it’s a very strong recommendation for people to get treated if they are high risk or very high risk,” says Dr. Humphrey.

Dr. Humphrey also notes that we have fewer data on patients at moderate risk of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporotic fracture because such patients are generally not included in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis studies, which is partly why these recommendations are conditional instead of strong. “But we really want people at moderate risk to be treated, too,” she says.

Ruth Jessen Hickman, MD, is a graduate of the Indiana University School of Medicine. She is a freelance medical and science writer living in Bloomington, Ind.

Ruth Jessen Hickman, MD, is a graduate of the Indiana University School of Medicine. She is a freelance medical and science writer living in Bloomington, Ind.

References

- Humphrey MB, Russel L, Danila, M, et al. 2022 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis. [These recommendations are included in a full manuscript, which was submitted, peer review pending, for publication in Arthritis & Rheumatology and Arthritis Care and Research.] https://rheumatology.org/glucocorticoid-induced-osteoporosis-guideline.

- Huette P, Abou-Arab O, Djebara AE, et al. Risk factors and mortality of patients undergoing hip fracture surgery: A one-year follow-up study. Sci Rep. 2020 Jun;10(1):9607.

- American College of Rheumatology Task Force on Osteoporosis Guidelines. Recommendations for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1996 Nov;39:1791–1801.

- Buckley L, Guyatt G, Fink HA, et al. 2017 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017 Aug;69(8):1095–1110. Erratum: Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017 Nov;69(11):1776.

- Tu KN, Lie JD, Wan CKV, et al. Osteoporosis: A review of treatment options. P T. 2018 Feb;43(2):92–104.

- Saag KG, Shane E, Boonen S, et al. Teriparatide or alendronate in glucocorticoidinduced osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2007 Nov;357(20):2028–2039.

- Anastasilakis AD, Makras P, Yavropoulou MP, et al. Denosumab discontinuation and the rebound phenomenon: A narrative review. J Clin Med. 2021 Jan;10(1):152.

- El Miedany Y. FRAX: Re-adjust or re-think. Arch Osteoporos. 2020 Sep;15(1):150.