The ACR’s “Report on Reasonable Use of Musculoskeletal Ultrasonography in Rheumatology Clinical Practice” makes it clear that using the technology for specific purposes is reasonable if conducted within the context of an overall clinical evaluation by a rheumatologist who has been trained in its use.1

“This report should help rheumatologists who are interested in performing musculoskeletal ultrasound [MSUS] blend it into their practice in an acceptable manner,” says Tim McAlindon, MD, MPH, chief of rheumatology at Tufts Medical Center and professor of medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston. The document “should stimulate thought about how we integrate ultrasound into fellowship training programs, how we train ourselves, and how we certify rheumatologists as competent in musculoskeletal ultrasound,” he says. Dr. McAlindon was principal investigator for the project and first author of the document.

The term “reasonable use” has significant meaning in the document. First, there is no requirement or implication that MSUS must be performed in a rheumatologic assessment, only that it can reasonably be used as an additional or complementary part of an evaluation and for specific purposes that are listed in the document. Second, reasonable use of MSUS, as defined in the document, means that the health benefits provided by MSUS will outweigh any adverse consequences. And third, MSUS should not be used if a clinical evaluation has already established a diagnosis with a high level of confidence.

“We wanted this to be viewed as an optional modality that rheumatologists could use, not as one that could be advocated as a standard of care,” says Timothy S. Shaver, MD, a member of the voting panel for the project. “I hope that more rheumatologists will consider using it and will be better educated about the broad spectrum of applications that MSUS has for rheumatology and will gain a better appreciation of the scope of the pathologies that MSUS can evaluate,” says Dr. Shaver, who is clinical associate professor at the University of Kansas and a rheumatologist in practice at Arthritis and Rheumatology Clinics of Kansas in Wichita.

William Arnold, MD, a rheumatology partner at Illinois Bone and Joint Institute, LLC, in Morton Grove, and a member of the project’s expert panel, says that, “for the first time, the document defines the field of rheumatology ultrasound as we understand it, based on literature review, expert panels, and use of the RAND/UCLA methodology.” It is not meant to be used as a “prescriptive” document, he adds, because it does not endorse any specific use of MSUS for any specific indication. “For the purposes of MSUS, the ACR has carved out part of the field and says these are reasonable procedures that rheumatologists can perform, but with two caveats: that it be done as part of a comprehensive evaluation that includes history, physical, and laboratory studies; also, it is assumed that the rheumatologist is able to perform the procedure.”

Although no exact figures are available, an estimated 15% to 30% of rheumatology practices in the United States use MSUS. According to Dr. McAlindon, some rheumatologists do not support its use because they are unsure whether it would improve clinical practice, and others are concerned about its potential overuse. This document, he says, should stimulate more dialogue and will hopefully encourage the development of training programs for fellows and a certification standard. “The technology itself, its safety, and its palpable benefits will stimulate more rheumatologists to adopt it; the trainees are already adopting it readily,” he says.

There is a lot of convincing documentation about the general utility of MSUS and what it can reveal. “It is certainly very promising technology and also very low risk. When we think of reasonable use, it has very broad applicability,” he adds. MSUS may make “one-stop rheumatology” a more likely reality. A rheumatologist may be able to come up with a more definitive diagnosis at the point of care without needing to send the patient out for additional testing, he says.

Clinical Scenarios Define Use

The document lists 14 clinical scenarios where MSUS can reasonably be used, with just one of those supported by Level A, or the highest, evidence: use of MSUS to guide articular and periarticular aspiration or injection at certain sites, including the synovial, tenosynovial, bursal, peritendinous, and perientheseal areas. According to Dr. Shaver, who has been performing MSUS for several years, its use for this purpose can improve accuracy. “Sometimes it will tell me, when I view the area, that the procedure I thought I would be doing is not the procedure I should be doing. I may be injecting a tendon sheath instead of a joint, or I may be aspirating fluid when I didn’t think there was fluid there, so it can change my approach to the procedure.”

Another key point among the 14 is that MSUS can be used to monitor disease activity and structural progression in patients with inflammatory polyarthritis. Disease activity and structural progression can be monitored at the glenohumeral, acromioclavicular, elbow, wrist, hand, metacarpophalangeal, interphalangeal, hip, knee, ankle, foot, and metatarsophalangeal sites. Power Doppler, a feature of MSUS, correlates with radiographic progression of rheumatoid arthritis erosions and predicts subsequent development of erosions.

Dr. Arnold, who has been using MSUS in his practice since 2002, says MSUS plays a particularly important role in this type of diagnosis. “There is growing literature about the value of diagnosing RA early and monitoring effective treatment. If we can prevent bone erosion early on, we can prevent disability,” he says.

According to Dr. Shaver, MSUS allows him to see a greater degree of erosion in the joint than he was previously able to detect with plain radiography. “I found that I was sometimes underestimating the level of degree activity the patient had and underestimating the degree of structural damage that was present when I used more traditional methods of evaluation.”

MSUS can also be useful for diagnosis of gouty arthritis by detecting urate crystals on the surface of cartilage in joints that may be symptomatic or asymptomatic, and also by detecting microtophi, which are invisible on X-rays. This use could significantly change the detection and management of gout in the future, experts contacted for this article predict.

Other reasonable uses of MSUS include:

- To evaluate evidence of enthesopathy for a patient with inflammatory-sounding entheseal, sacroiliac, or spine pain.

- To evaluate underlying structural disorder for a patient with shoulder pain or mechanical symptoms, without definitive diagnosis on clinical exam—but it should not be used for adhesive capsulitis or as preparation for surgical intervention.

- To evaluate for inflammation, tendon, and soft tissue pathologies at the shoulder, elbow, hand, wrist, hip, knee, ankle, and foot.

- To evaluate parotid and submandibular glands in a patient being evaluated for Sjögren’s disease.

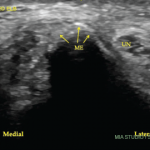

- To diagnose entrapment of the median nerve at the carpal tunnel, ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel, and posterior tibial nerve at the tarsal tunnel in patients with no definitive diagnosis on clinical examination.

- To evaluate effusion, intraarticular, and periarticular lesions, and adjacent regional soft tissues structure in the hip region.

- To facilitate clinical assessment at the glenohumeral, acromioclavicular, elbow, wrist, hand, metacarpophalangeal, interphalangeal, hip, knee, ankle/foot, and metatarsophalangeal joint for patients whose joints are obfuscated by adipose or other local derangements of soft tissue.

- To provide guidance during synovial biopsy procedures.

MSUS procedures that are not considered reasonable due to concerns about risks include evaluation of giant cell arteritis, eoiosinophilic fasciitis, myositis, numerous sites of nerve entrapment (other than median nerve at the carpal tunnel, ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel, and posterior tibial nerve at the tarsal tunnel), and as an outcome measurement of osteoarthritis. The designation as a not reasonable use for giant cell arteritis evaluation may be controversial for some. However, the committee decided not to support MSUS use for that purpose due to concerns about the potential for operator proficiency, as well as the high risk of missing a diagnosis and the imperfect sensitivity of the test.

For the Future

The ACR recommendations should help with reimbursement difficulties encountered by rheumatologists, although experts contacted for this article report few problems in the past, except in academic settings where it has been more difficult. Use of the RAND/UCLA methodology precluded any judgments about the cost effectiveness of the procedure. Some studies have reportedly found that MSUS can result in cost savings when compared with MRI because of reduced utilization, reduced time to diagnosis, and reduced number of visits needed to treat a condition, but more research is needed.

More importantly, the recommendations stress the need for establishing benchmarks for determining proficiency of MSUS use by rheumatologists. “My strong expectation is that there will eventually be a certification standard,” Dr. McAlindon says. “The first question was whether it’s reasonable to be doing this, and the broad answer now is ‘yes.’ So, the next questions are, how do we make sure people are trained, how do we integrate training into our fellowship programs, and how do we show that this is a worthwhile endeavor? These are all downstream questions.”

Kathy Holliman is a medical journalist based in New Jersey.