Natalya Kokhanova / shutterstock.com

Recognizing that situations involving ties with the pharmaceutical industry and conflicts of interest are often not black and white, the ACR’s Committee on Ethics and Conflict of Interest has collected feedback on four ethically challenging scenarios to gauge how rheumatology providers think about them.

The survey generated responses that were often mixed, showing that when it comes to the most difficult questions regarding conflicts of interest, rheumatology providers are often not on the same page. The survey results offer a window into the challenge of trying to come to clear conclusions about the course of action that is proper in situations when industry connections and patient care predictably become intertwined.

Background

The committee decided to start working on the feedback before recent news events propelled questions about conflict of interest in the medical field into the spotlight. But it comes as examination of the topic by the public intensifies. In September 2018, the chief medical officer for Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center resigned after reports that he didn’t disclose financial stakes in the outcomes of studies he published. Other questions about conflicts of interest at the center have also surfaced, and the center has since made changes to its policy.

Jane Kang, MD, MS, chair of the ACR’s Ethics & Conflict of Interest Committee, says the ACR thinks about conflict of interest in an ongoing way, and the survey wasn’t a reaction to news events.

“It helps everyone rethink conflict of interest again,” says Dr. Kang, associate professor of medicine at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York. “The ACR was already thinking about various conflict of interest considerations. The combination of real-world events and managing conflicts of interest for the ACR inspired us to explore it further.”

The Details

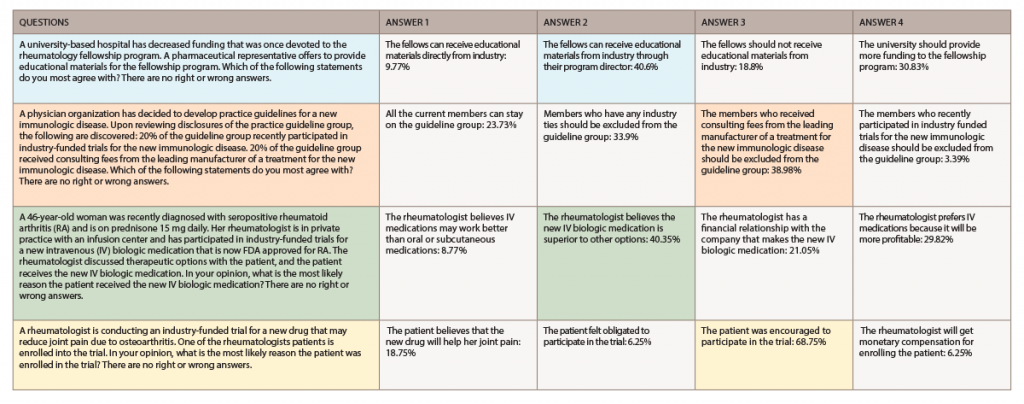

In the survey, the committee presented 2018 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting attendees with four situations, each with four statements in response to the situations (see table, below). Attendees were asked to pick the statement they most agree with. For three of the four situations, three of the statements received percentages of votes that were within about 20 points of one another, indicating an interesting divide in viewpoints. A statement was chosen by a majority of respondents for just one of the proposed scenarios. The survey emphasized there were “no right or wrong answers.”

The scenarios were chosen after members of the Ethics Committee submitted a case and a question. Dr. Kang, who has training with survey research, found most of the scenarios fit into one of four buckets and chose a question to represent each of those areas. She then edited the cases and answers so the wording was appropriate for generating useful results.

One scenario dealt with an issue addressed recently in published literature: conflicts of interest and clinical practice guidelines. In the scenario, a physician organization has decided to write a guideline for a new immunologic disease. Disclosure statements showed that 20% of the guideline group recently participated in an industry-funded trial involving the disease, and 20% received consulting fees from the leading manufacturer of a treatment for the disease.

Meeting attendees were asked which statement they most agree with: 1) All of the current members can stay on the guideline group; 2) members who have industry ties should be excluded from the guideline group; 3) members who received the consulting fees from the leading manufacturer of a treatment for the new immunologic disease should be excluded from the guideline group; or 4) members who recently participated in industry-funded trials for the new immunologic disease should be excluded from the guideline group.

The most common choice was No. 3, with 38.98% of responses, but choice No. 2, with its tighter restriction, was a close second (33.9%). About 24% said all the current members could stay on the guideline group.

In another scenario, a 46-year-old woman was recently diagnosed with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and is on 15 mg of prednisone a day. Her rheumatologist is in private practice with an infusion center and has participated in industry-funded trials for a new intravenous (IV) biologic medication that is now approved by the FDA for RA. The doctor discussed the options with the patient, and the patient received the new IV biologic.

Attendees were asked what they thought was the most likely reason the patient received the new IV biologic medication: 1) the rheumatologist believes IV medications may work better than oral or subcutaneous medications; 2) the rheumatologist believes the new IV biologic medication is superior to other options; 3) the rheumatologist has a financial relationship with the company that makes the new IV biologic medication; or 4) the rheumatologist prefers IV medication because it will be more profitable.

About 40% chose No. 2, and about 9% chose No. 1— meaning that about 49% assigned a primarily medical motive to the physician. But about 30% chose No. 4, and about 21% chose No. 3—meaning about 51% assigned a primarily monetary motive to the physician.

On how to handle a situation in which a pharmaceutical representative offers to provide educational materials for a fellowship program that has had its funding decreased, about 40% said the fellows should be able to receive the materials through the program director. But about 31% said the best choice was that the university should provide more funding.

In the final scenario, a rheumatologist is conducting an industry-funded trial on an osteoarthritis drug and a patient is enrolled into the trial. The most popular assessment by far—at 69%—was that the patient was encouraged to participate in the trial, and not that the patient believes the new drug will help her joint pain—a response that was chosen only by about 19% of survey takers.

The survey did not track how employer type—such as academic center or private practice—or other subgroupings responded to the questions.

Dr. Kang says she was intrigued by the split in opinion on the questions—although she was not entirely surprised by it because they are dilemmas that don’t have straightforward answers.

“Those are the situations that are quite complex, and I think that the answers reflect that—where people are divided on how they feel about these ethical dilemmas,” she says.

The ACR’s Position

The ACR requires its volunteers to provide disclosures at the time of nomination and at least yearly so the College can identify, evaluate and manage relationships that may pose “actual, potential or perceived conflicts.” The ACR also requires that everyone in a position to control continuing medical education content disclose all relevant financial relationships with any commercial interest within the past 12 months. Disclosures from the board of directors are posted on the ACR’s website.

Dr. Kang says it’s not adherence to existing policy—which is fairly clear-cut—that poses tough questions routinely for rheumatology providers. It’s the more nuanced situations that are vexing.

“There’s policy, and then there’s what’s really happening,” she says. “In reality, most situations are more gray and there is no clear, right answer. Some people may have very strong opinions. But most people, I think, are not quite sure what to do.”

There is no plan yet on whether and how to incorporate the survey feedback into the ACR’s activities and programming, Dr. Kang says.

“It was an informational, exploratory exercise to understand how people are thinking about these issues,” she says.

Dr. Kang says considering conflict of interest policies and scenarios is particularly important given the explosion of research interest in rheumatology.

“There’s this desire for us as physicians to advance the field, to develop, study and provide new therapies for patients who may not have the treatments that they need—and rheumatology is very exciting because we continue to have a lot of new options for treatment, which really has changed or can change our patients’ lives,” she says. “It just inevitably leads to more ties with industry.

“It requires continuous effort to manage that potential conflict or even the perception of conflict. It’s certainly a challenge, but we have to do it,” she says. “The major threat is losing the public’s trust. If the public doesn’t trust physicians, we won’t be able to do what we need to do to help patients. We have to be transparent to maintain the public’s trust.”

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance writer living in South Florida.