WASHINGTON, D.C.—Fatigue is a common and significant concern among people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) yet remains poorly understood and managed due to its complex etiology and the lack of evidence-based interventions to prevent it. Increasing recognition of the significant impact of fatigue in RA has led to ongoing research on its causes, ways to measure it, and potential prevention strategies. Rheumatologists were brought up to date on these efforts in a session titled, “The Puzzle of Fatigue in Rheumatoid Arthritis,” here at the 2012 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, held November 9–14.

Fatigue as a Psychophysical Symptom

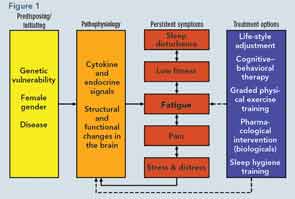

Presenting the latest research on the etiology of fatigue in RA, Rinie Geenen, PhD, professor of clinical and health psychology at Utrecht University in The Netherlands, spoke about the current model that emphasizes the combination of physiological and psychological/behavioral factors underlying fatigue. This model shows the important physiological role of genes, gender, and disease in the initiation of fatigue and the subsequent strong role that cognition and behavior play in the persistence of fatigue (see Figure 1).

“The inflammatory process indisputably plays a role in initiating fatigue,” he said, citing research that shows fatigue can be induced in animals by injecting substances that cause an increase of proinflammatory cytokines that resemble the RA disease process as well as by some research that shows a reduction in fatigue in people with RA treated with biologicals that block proinflammatory cytokines.

However, he emphasized that the precise physiological substrate of fatigue remains largely unknown and is complicated by other research that shows a low correlation between fatigue and other physiological indicators of inflammation, such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

What remains the strongest evidence and focus for intervention is the role of cognitive and behavioral factors that contribute to the persistence of fatigue. “Fatigue is much more strongly correlated with cognitive variables, such as helplessness and catastrophizing thoughts, and behavioral variables, such as pacing of activities, physical fitness, and patterns of sleep and awakening,” he said.

Of critical importance for rheumatologists in helping patients with RA manage their fatigue is to recognize its complex etiology, to recognize that it remains a largely invisible experience that is communicated nonverbally by the patient, and to consider behavioral means to target fatigue such as lifestyle, cognitive, and physical exercise interventions.

Including the Patient Perspective

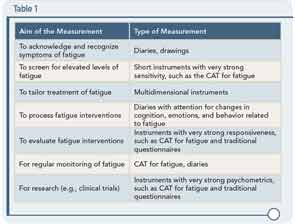

Although fatigue can be difficult to measure, Christina Bode, PhD, assistant professor of psychology, health, and technology at the University of Twente in The Netherlands, reviewed a number of novel measurements of fatigue that can be useful in helping to tailor intervention strategies. Along with a number of validated instruments, tools based on the patient perspective can help provide a more nuanced and helpful guide to managing fatigue. These include daily diaries or drawings as well as the development of computer adaptive testing (CAT) for fatigue in RA that she and her colleagues incorporate in their assessments. She emphasized that there is not a singular optimal measurement tool for fatigue; rather, the challenge is choosing the appropriate tool that matches the aim of measurement.

For example, Dr. Bode said that if a rheumatologist wants insight into the pattern of fatigue, a fatigue diary can be used. If the aim is to screen for elevated levels of fatigue, a brief instrument with strong sensitivity should be used. Other suggested instruments based on aims are shown in Table 1.

Overall, she emphasized the importance of regular monitoring of fatigue to provide options for how to improve symptoms of fatigue.

Nonpharmacological Interventions

Sarah Hewlett, PhD, professor of rheumatology nursing at the University of the West of England, described the current evidence from randomized clinical trials on the nonpharmacological treatment of fatigue in RA. Among the interventions examined that have shown efficacy in managing fatigue are physical activity (e.g., low-impact aerobic exercise, pool therapy, Tai Chi, resistance training) as well as psychosocial interventions (e.g., self-efficacy and/or goal setting, cognitive behavioral therapy).

However, she emphasized that most of these studies were limited by not addressing fatigue as the primary outcome of the study. She emphasized that future studies on fatigue need to better address what should be measured, what works in whom, long-term efficacy, as well as specific details of physical activity (e.g., timing, intensity, progression, tailoring motivators, maintenance) and psychosocial interventions (e.g., delivery by usual clinical teams).

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical journalist based in St. Paul, Minn.