WASHINGTON, D.C.—New and potentially vital insights into the factors that lead to bone erosion and formation could point the way to new treatments for the terrible effects that arthritic conditions can have on bone, an expert on the subject said during the Rheumatology Research Foundation’s Oscar S. Gluck, MD, Memorial Lectureship, “Bone Wasn’t Built in a Day,” at the 2012 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, held November 9–14.

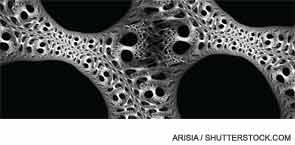

With forces vying for bone destruction and for bone creation, the healthy outcome is a draw between the two—but that often doesn’t happen in those with arthritic conditions, said Ellen Gravallese, MD, professor of medicine and cell biology at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Boston.

The result is bone loss in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and debilitating bone formation in conditions like ankylosing spondylitis. “Ultimately, there’s a balance between osteoclast-mediated bone resorption and osteoblast mediated bone formation,” Dr. Gravallese said. “And the question is, How is this balance maintained?”

Figuring out this process—and how it’s undermined in those with arthritic diseases—is a problem being tackled in laboratories throughout the world.

Reviewing Some Findings

Studies have found that bone edema is a sign of future bone erosion—one study of 55 patients found that synovitis and bone edema are independent predictors of erosion. “Areas of bone edema will likely result in an erosion if the patient is not treated,” Dr. Gravallese said. “However, early therapy can prevent progression to erosion.”1

In a finding now well known, the inhibition of RANK ligand has been identified as a way of keeping osteoclast precursor cells from differentiating into the cells that destroy bone.2

“This is one mechanism by which osteoclasts could be inhibited—that is, by inhibiting their differentiation,” Dr. Gravallese said. “And it’s been shown that the RANKL antibody has a profound effect on bone turnover.”

One area that has been a puzzle, she said, is why lupus patients seem to be more protected from erosion than RA patients, but there have been inroads into understanding this as well. A study out of the University of Rochester examined the role of interferon-alpha in a lupus mouse model as this process unfolds, yielding results that could have a bearing on clinical practice.

“Over time, as the mouse developed the lupus phenoytpe, interferon-alpha was increasingly produced—and during the phases of interferon-alpha production, erosion was not seen, even with arthritis, due to interferon-alpha expression,” Dr. Gravallese said. “This research showed that what interferon-alpha does in this model is to divert the precursor cells to a myeloid dendritic cell at the expense of osteoclast precursors. This might be one important mechanism by which lupus patients are protected from erosion.”

Paradigm-Shifting Paper

On the topic of bone formation, a “paradigm-shifting paper” was published this year, shedding light on the factors involved in the ability of inflammation to induce bone formation, Dr. Gravallese said. It showed that the cytokine interleukin 23, which is upregulated in ankylosing spondylitis, plays a “very critical role” in this process. It induces, in vivo, enthesitis and enthesial bone formation prior to synovitis.3

Another question that has largely stumped researchers—but that, if solved, could help lead to new therapies—is why bone repair is so rare in RA, happening in only approximately 10% of cases, even when erosion has been stopped with biological agents.

Dr. Gravallese’s lab examined osteoblast activity with respect to the amount of disease activity in mice with inflammatory arthritis. They saw bone formation rates rise and fall along with the severity of inflammation.

“What was really interesting to us about this is that inflammation had to almost completely resolve before the osteoblast precursors came in and lined the eroded bone surfaces and began to make bone,” Dr. Gravallese said. “This suggests that inflammation might be suppressing the ability of the osteoblast to form bone in this model.”

The Wnt signaling pathway has proven to be a crucial mechanism at work here. Wnt ligands help make osteoblast differentiation possible by stabilizing the protein beta catenin.

But there is a natural inhibition of this pathway: the Dickkopf (DKK) family of inhibitors and secreted Frizzled-Related proteins family of inhibitors are proteins that can interfere with Wnt function.

“There’s a great deal of evidence now that DKK1 can regulate bone formation and that it plays a role in rheumatic diseases,” Dr. Gravallese said.

The bottom line, she said, is that “inflammation leads to proinflammatory cytokine production and the upregulation of antagonists of the Wnt pathway,” but as inflammation wanes the process reverses and erosion repair is seen.

This all has “some interesting implications for rheumatoid arthritis,” she said. But she cautioned that, “we have to be careful because these animal models are models of acute inflammation whereas our patients with rheumatoid arthritis have chronic inflammation. And, therefore, chronic inflammation in the bone marrow could lead to an alteration in the mesenchymal precursor cell, so that perhaps there are no osteoblast precursors available to lay down bone.”

There are many clinical questions that remain, Dr. Gravallese said. For one thing, ultimately how important is it to heal erosions?

“We know that there are long-term functional consequences of erosions, but we have no evidence as of yet that healing of the erosion will alter that,” she said.

Other Considerations

It also is important to take cartilage loss into account. “I think that there are some very important implications of subchrondal bone erosion for cartilage loss,” Dr. Gravallese said. “Cartilage is attached to subchrondral so if subchrondral bone is eroded, you can lose cartilage secondarily. It is important to consider that cartilage loss may be affected by bone erosion.”

Plus, she said, if a lack of healing indicates that there’s persistent inflammation—something suggested though not proven by her lab’s work—then erosion could be an important surrogate marker or bioassay for persistent inflammation.

Also, she wondered, what the clinical impact of residual, low-grade inflammation in RA patients is on the cardiovascular system and the axial and appendicular skeleton—“in other words, How much inflammation do we really need to resolve before we no longer need to worry about these downstream effects?”

“I don’t have the answers to these questions,” she said, “but these are the kinds of things that we’ve been thinking about.”

Thomas Collins is a freelance medical journalist based in Florida.

References

- Bøyesen P, Haavardsholm EA, Ostergaard M, van der Heijde D, Sesseng S, Kvien TK. MRI in early rheumatoid arthritis: Synovitis and bone marrow oedema are independent predictors of subsequent radiographic progression. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:428-433.

- Cohen SB, Dore RK, Lane NE, et al. Denosumab treatment effects on structural damage, bone mineral density, and bone turnover in rheumatoid arthritis: A twelve-month, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1299-1309.

- Sherlock JP, Joyce-Shaikh B, Turner SP, et al. IL-23 induces spondyloarthropathy by acting on ROR-γt+ CD3+CD4-CD8- entheseal resident T cells. Nat Med. 2012;18:1069-1076.