WASHINGTON, D.C.—Knee osteoarthritis–related disability is a significant public health priority in the United States; it affects half of all adults over 65 years of age and leads to over 700,000 total knee replacement (TKR) procedures each year, making it the most common and costly inpatient procedure in Medicare, according to Patricia D. Franklin, MD, professor and director of clinical and outcomes research in the department of orthopedics and physical rehabilitation at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester. Although TKR has shown efficacy in improving pain, one word can describe current functional outcomes as well as postoperative rehabilitation strategies after TKR: variable.

Given this procedure’s burden on the U.S. healthcare system, efforts are underway to address variability in rehabilitation after TKR as well as patient factors associated with the variability in functional outcomes to improve both the management and outcomes of TKR. Dr. Franklin and other experts discussed this effort in a session titled, “Total Knee Arthroplasty Rehabilitation,” at the recent 2012 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, held here November 9–14. [Editor’s Note: This session was recorded and is available via ACR SessionSelect at www.rheumatology.org.]

Identifying Patients at Risk for Poor Functional Outcomes

About one-third of patients who undergo TKR do not experience improvement in physical function after surgery. Among the patient factors that have been shown to predict suboptimal function after TKR are older age, female sex, a body mass index greater than 40, poorer quadriceps strength, and poorer preoperative emotional health or physical function. Data also show that patients who undergo TKR also have evidence of symptomatic joint pain in multiple other joints as well, such as the hips, contralateral knee, and lumbar spine. According to Dr. Franklin, the evidence is building for the need to consider all of these factors when performing a TKR.

To that end, Dr. Franklin and her colleagues developed a research registry called FORCE-TJR (Function and Outcomes Research for Comparative Effectiveness in Total Joint Replacement) that uses patient-reported outcomes of pain relief and improved physical function to define clinical failure, rather than implant failure that is used by traditional TJR registries to define the need for surgical revision (www.force-tjr.org). The FORCE-TJR registry focuses on understanding the contribution of patient factors (e.g., age, sex, race, obesity, medical and musculoskeletal comorbidity, preoperative functional status, and socioeconomic position), as well as delivery (e.g., perioperative pathway, institutional volume, postoperative adverse events, deep venous thrombosis) and technology (e.g., cemented/uncemented) factors to TJR outcomes.

Currently, five core clinical centers and 26 community sites comprising 114 surgeons and 8,100 patients across 22 states are participating in the registry. According to Dr. Franklin, preliminary data show an improvement in pain relief in up to 86% of patients at the centers participating in the registry, but noted that she and her colleagues still want to understand the 14% reporting suboptimal results.

She emphasized the need to use TKR outcome measures that are appropriate to measuring TKR (i.e., pain, physical function, and joint stiffness) as well as ones that are accessible to clinicians and patients. The outcome measures must be reliable, valid, and responsive to change.

To this end, Dr. Franklin and her colleagues use both the SF-36 and Knee Injury Osteoarthritis Outcome Score and an estimated Western Ontario and McMaster OA Index, along with imaging to provide a more comprehensive picture of the severity of knee osteoarthritis.

Variability of Post-TKR Rehabilitation

Along with a greater understanding and assessment of the contribution of patient factors on TKR outcomes is the need to consider the variability in post-TKR rehabilitation on outcomes. Carol A. Oatis, PT, PhD, professor of physical therapy at Arcadia University in Glenside, Pa., presented data that show considerable variability in the timing and duration of rehabilitation following TKR. She noted that rehabilitation, including acute care followed by institutional or home care rehabilitation, typically lasts from nine to 18 days, depending on the site of care, with little data on further rehabilitation beyond this. She cited data showing the typical recovery trajectory following TKR, which show that men and women typically report improvement in physical function at 12 weeks that plateaus at four months. Based on this, Dr. Oatis posed the question that perhaps providing more or more standardized intervention between three weeks and four months after TKR may improve TKR outcomes.

Overall, Dr. Oatis said that, despite its prevalence, TKR lacks accepted clinical benchmarks or treatment strategies to direct interventions and that more research is needed to determine if a more standardized and evidence-based rehabilitation approach improves functional outcomes.

Recommendations for Best Practice

Marie D. Westby, PT, a postdoctoral fellow at the School of Public Health at the University of Alberta, and an Arthritis Research Centre of Canada trainee in Richmond, British Columbia, presented efforts to develop a more standardized approach to postacute TKR rehabilitation care. One effort was a systematic review of TKR she and colleagues undertook to assess postacute care. Based on seven studies published between 2003 and 2009 that included a total of 779 patients, the review showed that the quality of evidence is not sufficiently high or consistent enough to suggest that any one rehabilitation approach is superior. The review also showed key evidence gaps, including gaps in rehab parameters for optimal outcomes, outcome measures to routinely use in clinical practice and research, how adherence impacts outcomes, and which contextual factors have the strongest influence on outcomes and patient satisfaction.

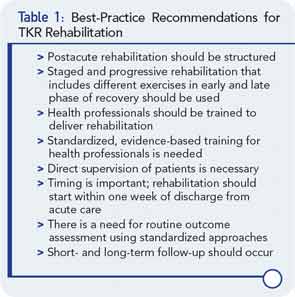

Westby then described a second effort to develop a more standardized approach to post-acute care using a formal consensus process to develop best practice recommendations. She and her colleagues used an online Delphi survey that included a panel of Canadian and American physical therapists, orthopedic surgeons, other physicians, other health professionals, and patients who have undergone TKR to develop consensus on key recommendations. Key recommendations for best practice of TKR are shown in Table 1. Among the types of interventions that the panel emphasized as important were exercise programs that included active range of motion, strength training, home exercises, dynamic balance, stair climbing, and rising from/lowering to a chair.

Overall, the consensus panel emphasized that the setting and format of postacute rehabilitation is less important than the type and intensity of intervention and knowledge and skill of the provider. It also emphasized the importance of integrating personal factors of the patient (e.g., functional status, psychological status, general health) and external factors (e.g., skills of the rehabilitation professional, support of spouse or family, access to rehabilitation programs) into the planning and delivery of postacute TKR rehabilitation.

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical journalist in St. Paul, Minn.