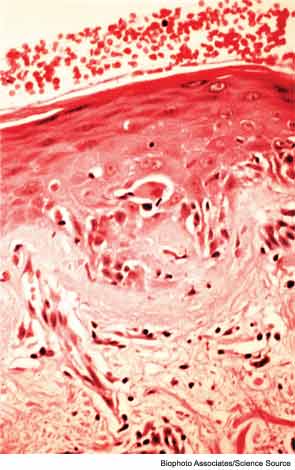

WASHINGTON, D.C.—Diagnosing myopathies—a group of diseases that includes polymyositis, dermatomyositis, and inclusion-body myositis—is a complex process. Patients may present with symptoms like unexplained muscle weakness or cramps. Further tests may detect elevated creatinine protein kinase levels or myositis-specific autoantibodies. Then, electromyogram (EMG) and muscle tissue biopsy may confirm the specific diagnosis, said a panel of experts in a session titled, “Diagnostic Assessments in Myopathy,” at the recent 2012 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, held here November 9–14. [Editor’s Note: This session was recorded and is available via ACR SessionSelect at www.rheumatology.org.]

Tests for Myopathy-Associated Autoantibodies

Testing for myospecific and myopathy-associated autoantibodies may aid diagnosis of these neuromuscular diseases, said Hector Chinoy, PhD, program director of clinical rheumatology at the University of Manchester in England. Seropositivity is found in as many as 70% of myositis patients and in about 60% of juvenile myositis patients, he said. Risk factors for myositis includes patients with human leukocyte antigen class genes, particularly the DRB1*03 haplotype. Both environmental and genetic risk factors come into play in assessing risk of myositis. “Smokers who are also DRB1*03 positive are at much higher risk” of developing anti-Jo1 antibodies, which are strongly associated with myositis, he said.

Other environmental exposures, as well as certain drugs and infectious agents, play a role in triggering the development of or activation of these diseases, he added. Ultraviolet radiation exposure is one risk factor, and patients are more likely to have one or more of the 15 myositis-specific autoantibodies if they live near the equator, for example. In addition, 75% of patients with necrotizing myopathy in one study had been exposed to statins, Dr. Chinoy added.

Patients with anti-Jo1 autoantibodies may present obvious symptoms like dry, cracked fingers, Raynaud’s phenomenon, interstitial lung disease, and abrupt fever, with or without myositis. In other conditions, like amyopathic dermatomyositis, a distinct rash may precede the development of myositis, Dr. Chinoy said. “If you’ve got a myositis-specific antibody, you’ve got your diagnosis,” he said.

In cancer-associated myositis, the most common autoantibody is TIF1γ, which is not found in other autoimmune diseases or in healthy individuals, Dr. Chinoy noted. One noteworthy sign of this condition is a shawl-like rash on the torso, he explained. For patients with TIF autoantibodies, malignancy association is dependent on age, and is more common in people over 45. “Children and juveniles tend not to get cancer, although you still need to be vigilant when TIF1γ is present,” he said. Exclude nonspecific autoantibodies to help confirm diagnosis of myositis, he concluded.