WASHINGTON, D.C.—A number of new oral anticoagulants now available in the United States will eventually be used to treat autoimmune and rheumatologic diseases associated with hypercoagulability complications, such as antiphospholipid antibody syndrome or catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome, and rheumatologists will need to begin to understand their appropriate use and potential complications, according to Craig M. Kessler, MD, professor of medicine and pathology and director of the coagulation laboratory in the department of pathology and laboratory medicine at Georgetown University’s Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center in Washington, D.C.

To help rheumatologists become familiar with the new anticoagulants and how to determine their appropriate use in clinical situations, Dr. Kessler presented information on a new paradigm for coagulation, as well as advantages and disadvantages of the new anticoagulants, during a session titled, “New Anticoagulants: What a Hematologist Thinks a Rheumatologist Needs to Know!” at the 2012 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, held November 9–14. [Editor’s Note: This session was recorded and is available via ACR Session Select at www.rheumatology.org.]

Dr. Kessler shared his experience as an expert in disorders of anticoagulation to highlight what he thinks is essential for rheumatologists to know. To illustrate the indications and risks of anticoagulation, he presented a number of case studies that show how autoimmune diseases can be treated by modulating the B cell that is involved with producing antibodies—a strategy, he said, that underlies the treatment of many rheumatologic and hematological diseases, due to similar pathological etiologies.

New Paradigm of Coagulation

Dr. Kessler laid the foundation for understanding the role for the new oral anticoagulants by describing a new paradigm of coagulation that helps explain how rheumatological diseases trigger coagulation. In the older paradigm, described as a coagulation cascade, the thought was that tissue damage to the extrinsic circulating tissue factor and clotting factor VIIA complex activates the intrinsic pathway factor IX to initiate generation of thrombin for fibrinogen cleavage and fibrin formation.

According to Dr. Kessler, in the new paradigm, described as normal hemostasis, tissue-factor bearing cells are the mainstay of coagulation in which the process of FVIIa-tissue factor complex formation occurs on the surface of tissue factor laden cells, such as monocytes and macrophages. “These cells are critical to the symptomatology and progression of autoimmune diseases and links inflammation with coagulation,” he said, adding that new treatment strategies can be developed based on this new understanding of how rheumatological diseases trigger coagulation.

New Anticoagulants: Pros and Cons

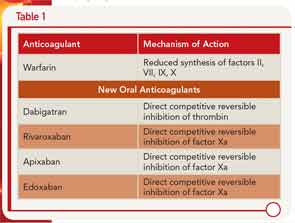

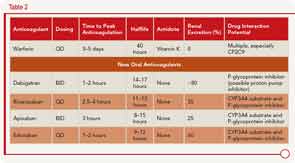

Dr. Kessler described the pharmacology of the new oral anticoagulants along with warfarin, including the different mechanisms of action (see Table 1) and clinical application (see Table 2).

A number of advantages and disadvantages should be weighed when considering use of one of these new anticoagulants over warfarin, he said. The advantages include lower rates of stroke and mortality, along with lower rates of intracerebral hemorrhage (although the rates of gastrointestingal bleeding are higher) compared to warfarin. One of the main advantages, he said, is that these anticoagulants are more convenient to use because they don’t require the type of regular monitoring that warfarin requires.

However, the lack of monitoring could also affect adherence adversely, he said. Other disadvantages of the new anticoagulants include the short half-life, which may not benefit patients with limited adherence, as well as the inability to titrate doses and the high cost of these drugs. One main disadvantage, he said, is that these new anticoagulants have no antidote. To address this, he cited a study by Kaatz et al. that provides some information and suggestions on reversal of three of the new anticoagulants, apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban.1 For example, oral activated charcoal can be used to reverse all three of these anticoagulants, whereas fresh frozen plasma will not be effective for any of these.

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical journalist based in St. Paul, Minn.

Coagulation Case Study

Patient description: A 35-year-old Caucasian female with a known longstanding history of systemic lupus erythematosis responsive to corticosteroids and without evidence of end organ failure presents with left lower extremity (LLE) asymmetric swelling and pain. Duplex Doppler ultrasounds confirm the presence of LLE proximal deep venous thrombosis (DVT) extending from the mid-calf to the mid–proximal thigh. Her SaO2 was 88% on room air; the CT pulmonary angiogram revealed multiple bilateral pulmonary emboli with low clot burden.

Laboratory data: Complete blood count: platelets=140,000/µL; 5,000 white blood count/absolute neutrophil count=12,000; hemoglobin/hematocrit=10.8/32; D-dimer=900 mcg (0-200); prothrombin time=12.5 seconds; activated partial thromboplastin time=32.5 seconds; fibrinogen=250 mg/dL. Complete metabolic profile revealed normal liver function tests and renal function.

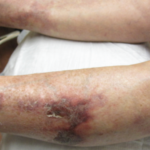

Initial Management: The patient was treated with low–molecular weight heparin (LMWH), and her LLE swelling and pain resolved. She was discharged on Day 3 with overlapping LMWH and warfarin. On Day 9 postvenous thrombosis, she noted easy bruisability, persistent epistaxis, and now right lower extremity swelling and pain, associated with new onset of pleuritic chest pain and dyspnea. She returned to the ER and was diagnosed with a new pulmonary embolism and proximal DVT. Her blood pressure was 85/45, and pulmonary artery pressure on echo was 45 mm. Laboratory data: international normalized ratio was 1.3 on LMWH and warfarin bridging; platelets=10,000; hemoglobin/hematocrit=8.5/23.3; white blood count=12,000.

Recommended action: Obtaining a platelet factor 4-heparin enzyme–linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA) and serotonin platelet release and discontinuing anticoagulation and inserting a retrievable inferior vena cava filter are recommended.

Subsequent diagnosis: Patient likely has heparin-induced thrombocytopenia with thrombosis, and PF4-heparin ELISA and serotonin platelet release assays are appropriate to make that diagnosis. Thrombolysis would be helpful for large pulmonary emboli and decompensated cardiac function but is not advisable because of the presence of low platelets. Similarly, use of argatroban and oral anti-II specific anticoagulations, which carry a high risk of bleeding complications, are not advised. These measures could be considered if, after discontinuation of LMWH, the patient’s platelet counts normalized over 80,000/µL. Lastly, bone marrow will not be specific enough to differentiate between peripheral platelet destruction due to heparin-induced thrombocytopenia versus idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). However, the scenario is less consistent with ITP.