ARTFULLY PHOTOGRAPHER/shutterstock.com

WASHINGTON, D.C.—In the next 15 years, it will be increasingly difficult to provide adequate care for rising numbers of patients with rheumatic diseases due to a severe shortage of trained rheumatology healthcare providers, according to the ACR’s 2015 Workforce Study of Rheumatology Specialists in the United States.

The full study is available online, and panelists from private practice and academic centers led a discussion on the study’s findings and ideas to address workforce shortages at a Nov. 14, 2016, session, The Rheumatology Workforce: Present and Future, at the 2016 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting.

“By 2025, the U.S. will face a shortage of physicians. Of course, this will impact primary care a lot, but in some cases, the rheumatologist is the primary care provider for our patients,” said Daniel F. Battafarano, DO, MACP, FACR, a rheumatologist at San Antonio Military Medical Center in Texas, and co-chair of the Workforce Study Group with Seetha U. Monrad, MD, at the University of Michigan. The new ACR workforce data mirror what other subspecialties of medicine face today, he said.

Numbers Reveal a Crisis

This is the first major rheumatology workforce analysis since the ACR’s 2005 study, Dr. Battafarano said.1 It used an integrated model that combined supply and demand–based methodologies, socioeconomic factors driving patient demand, epidemiological factors that drive healthcare needs, existing training processes and healthcare utilization rates. Electronic surveys of ACR and ARHP members measured patient workload and demographics.

Not every rheumatologist sees the same number of patients each week, so the study group adjusted gross numbers of providers to calculate the number of clinical full-time equivalents (FTE) available to treat patients. Based on average clinical workload, a rheumatologist in private practice was measured as one clinical FTE, while someone working in an academic setting was measured as 0.5 FTE. The study assumed that 80% of the current adult U.S. rheumatology workforce is in private practice and 95% of pediatric workforce is in an academic setting. The clinical FTE for academic pediatric rheumatologists may be significantly underestimated at 0.5 clinical FTE, and this warrants further analysis.

The 2015 study estimated both NPs and PAs in the current workforce, and these providers counted as 0.8 clinical FTE. Currently, about 5% of all NPs and 1.9% of all PAs work in rheumatology, the study found.

Patient demand, or U.S. adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis, is projected to rise from 52.5 million in 2012 to 67 million by 2030, according to the study.

“In the past, we were able to get a good head count of board-certified rheumatologists, but they weren’t all full-time, practicing clinical physicians, and some were retired or in industry,” said Dr. Battafarano. “Also, as people plan to retire, they start to decrease their patient workload in their last five to 10 years before retirement. So we have incremental part-time employment before rheumatology providers actually retire.”

The study group estimates that 50% of adult rheumatologists and 32% of pediatric rheumatologists practicing now will retire in the next 10 years, he said.

Soaring Gaps

Patient demand, or U.S. adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis, is projected to rise from 52.5 million in 2012 to 67 million by 2030, according to the study. Demand is based on projections of increased rheumatic disease diagnoses by 2030 and an estimate that 25% of a rheumatologist’s patients will have OA.

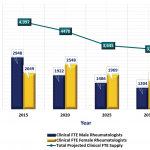

With the soaring patient demand, current and projected figures indicate the rheumatology workforce will be insufficient to meet that demand, Dr. Battafarano said. Here are some of the study’s crucial findings:

- Estimated 2015 adult rheumatology workforce: 5,595 (adjusted to 4,497 clinical FTE)

- Projected 2030 adult rheumatology workforce: 4,246 rheumatologists (adjusted to 3,455 clinical FTE)

- Projected physician need to meet adult patient demand in 2030: 8,184

- Estimated 2015 pediatric rheumatology workforce: 300 (adjusted to 287 clinical FTE)

- Projected 2030 pediatric rheumatology workforce: 251 total providers (adjusted to 231 clinical FTE)

- Projected physician need to meet pediatric patient demand in 2030: 461

The 2005 ACR study recommended that the subspecialty should increase adult and pediatric fellow positions, facilitate a Web-based curriculum for NPs and PAs, analyze practice efficiency and promote advocacy for a value-based rheumatology care and compensation model, said Dr. Battafarano. Rheumatology fellows’ slots were increased overall and, today, about 90% of the adult positions and 50% of the pediatric positions are filled.

Dr. Battafarano said the question arises, “Can’t we just solve this problem with graduate medical education?” He said, “There are 107 adult fellow FTEs coming into our workforce every year, but that cannot compensate for the approximate 220 adult retirements per year. So GME training alone is not the answer.” He added that only half of pediatric rheumatology fellowship slots in 36 programs are currently filled.

According to the study’s findings, in 2015, there were an estimated 248 active NPs working in adult rheumatology, or 228 clinical FTEs, and an estimated 22 NPs working in pediatric rheumatology, or 20 clinical FTEs. The NP rheumatology workforce is expected to increase to 313 adult clinical and 24 pediatric FTEs by 2025. The 2015 study also revealed that 207 clinical FTE PAs are working in adult rheumatology and four clinical FTE PAs are working in pediatric rheumatology now, and by 2025, there will be 263 adult and five pediatric PAs.

“Although the NP and PA rheumatology provider data may be limited, the projected NP and PA increases will not significantly compensate for the overall workforce shortages over the next 10 years,” said Dr. Battafarano.

Demographics & Geography

A dramatic shift in the demographics of rheumatologists will occur over the next 15 years. Men made up 60% of the 2015 adult rheumatology workforce, but by 2030, 60% will be women, Dr. Battafarano said. Currently, 68% of pediatric rheumatologists are women. Rheumatology currently lacks ethnic diversity: 80% of the study’s survey respondents identified as non-Hispanic and 75% as white.

The rheumatology workforce is unevenly distributed around the country as well, he said. “In the Northeast, there are 1,262 rheumatologists, which represents 21% of our adult rheumatologists, and 26,719 adult patients per rheumatologist,” said Dr. Battafarano. “Shift your attention to another region—the Southeast, [and] you will find that 11% (or 698 total) of our rheumatologists are down there. But the ratio of patients to rheumatologist is much different: 60,087 adult patients per rheumatologist. Access to care in that area is already more strained.”

Pediatric rheumatologists also are unevenly distributed around the country, with 24.8% in the Northeast and 2.4% in the Southwest, the study noted.

How to Meet the Challenge

Panelists shared some ideas to address workforce shortages and improve access to care:

Redistributed patient care: Primary care physicians could manage more patients—those with OA or gout and who don’t require complex, multi-treatment care—without rheumatology consultation, said John FitzGerald, MD, PhD, interim chief of rheumatology at the University of California Los Angeles. “But there are shortages in primary care, too, so simply pushing more patients back on primary care will not be an adequate solution,” he said.

Invest in NP & PA training: Rheumatologists should reach out to local schools to train and recruit more NPs and PAs, said Kori Dewing, DNP, ARNP, a nurse practitioner at Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle. “We can show NPs and PAs that rheumatology is an exciting place to be. If they see this early in their training, they can focus some of their additional training in rheumatology and come out passionate for this career path,” said Dr. Dewing.

New technology: Telemedicine often is touted as a potential way to expand care, but its exact role in rheumatology is uncertain, said Dr. Battafarano. “There have been many successful pilot programs with medical centers at the intrastate level. This is an area that needs to be actively pursued and studied for screening consults, management advice and timely access to rheumatologic care.”

Identify pools of potential rheumatologists: It’s important to learn more about the medical schools and residency programs worldwide that produce our fellows, said V. Michael Holers, MD, head of the division of rheumatology at the University of Colorado, Denver. “We know very little about our prefellowship pipeline. We don’t know, as an academic organization, which medical schools or hospitals overseas are sending fellows to us, so we can model best behaviors. If we support educators, rheumatologists who have access to residents and medical students, they will recruit new rheumatologists into the pipeline,” he said.

More data may help make the case for more funds to invest in recruitment and training efforts. “Mentoring and access to mentors brings students into rheumatology. From a division director’s perspective, this is a crisis in many ways, but it’s only catastrophic if we ignore it.”

Susan Bernstein is a freelance medical journalist based in Atlanta.

Reference

- Deal CL, Hooker R, Harrington T, et al. The United States rheumatology workforce: Supply and demand, 2005–2025. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2007 Mar;56(3):722–729.