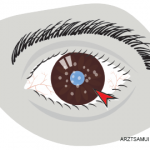

Researchers have peppered the medical literature with an increasing number of clinical trials designed to test the efficacy and safety of treatments for uveitis, a collection of ocular diseases characterized by intraocular inflammation. Unfortunately, few of these trials have targeted childhood uveitis, which can cause blindness. This past spring, researchers published some much-needed good news: the results of the SYCAMORE trial of adalimumab in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)-associated uveitis. The trial revealed that children and adolescents with active JIA-associated uveitis who were taking a stable dose of methotrexate had reduced inflammation and a lower rate of treatment failure if they also received adalimumab.

Researchers have peppered the medical literature with an increasing number of clinical trials designed to test the efficacy and safety of treatments for uveitis, a collection of ocular diseases characterized by intraocular inflammation. Unfortunately, few of these trials have targeted childhood uveitis, which can cause blindness. This past spring, researchers published some much-needed good news: the results of the SYCAMORE trial of adalimumab in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)-associated uveitis. The trial revealed that children and adolescents with active JIA-associated uveitis who were taking a stable dose of methotrexate had reduced inflammation and a lower rate of treatment failure if they also received adalimumab.

Athimalaipet V. Ramanan, FRCPCH, FRCP, professor of pediatric rheumatology at the University of Bristol in the U.K., and colleagues also found that patients who received adalimumab had a much higher incidence of adverse and serious adverse events than those who received methotrexate plus placebo. They published the results of their randomized, placebo-controlled trial in the April 27 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.1

The study’s primary endpoint was treatment failure based on a multi-component intraocular inflammation score. This score included the anterior chamber cell count, which is known as the standardization of uveitis (SUN) criteria. The investigators acknowledge in their paper that the SUN criteria are not currently validated in children.

The team found that treatment with adalimumab significantly delayed the time to treatment failure relative to treatment with methotrexate alone (hazard ratio, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.12 to 0.49; P<0.0001). In fact, the researchers terminated the trial early because of this strong beneficial effect of adalimumab treatment. This prespecified stopping criterion was met after 90 of 114 patients were enrolled in the trial. All told, the investigators documented a 27% treatment failure rate in adalimumab-treated patients and a 60% treatment failure rate in methotrexate-plus-placebo-treated patients. Unfortunately, patients treated with adalimumab also experienced more adverse events, such as minor infections, respiratory disorders and gastrointestinal disorders, than patients treated with methotrexate plus placebo.

Methotrexate Treatment

In an accompanying editorial, Jennifer E. Thorne, MD, PhD, professor of ophthalmology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, notes that because the trial was performed in children who had active disease despite methotrexate treatment, it’s likely the results cannot be generalized to all patients being treated for JIA-associated uveitis.2

The role of methotrexate in the outcomes was further discussed in later correspondence with the editor. A letter by Shiqiao Peng, PhD, and colleagues at the First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University in Shenyang notes that children received methotrexate either orally or via subcutaneous injection, a difference that may have affected outcomes in the study.3