We are using iterative quality improvement methods to create effective care teams and using a simple HIPAA-compliant disease registry to enroll and track all our RA patients (see Figure 1, opposite). The registry data set includes patient and physician identifiers, year of onset, disease activity measures and medications by date, and whether individual patients’ management can be changed. These data are feasible for physicians and staff to collect and use in busy practice environments. All other data go into each patient’s medical record as usual.

We have labeled this different approach to care for chronic diseases Clinical Population Management. Project progress was shared at the 2014 and 2015 ACR/ARHP Annual Meetings and previously published in The Rheumatologist.5

Here’s what we’ve learned so far:

1. Managing chronic diseases without a disease population registry is like trying to manage O’Hare Airport without an air traffic control system: There are 600 planes up there somewhere, but you can only see the ones in sight and have no idea what’s going on with the rest. A disease population registry allowed us to understand for the first time how many RA patients we manage; who they are; when their disease activity was last assessed; who is overdue; what percentages have high, moderate, low and controlled disease; how we are treating them; and how well we are controlling their disease. Electronic health records generally don’t provide this information because each patient’s data are filed by encounters, and population analytics are missing.

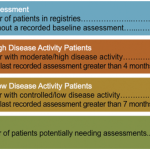

The baseline RAPP practice registry data weren’t pretty.4 We had more RA patients (median 585) than we had thought, and our assessments were only on time for about 40% of our populations using minimum standards from the treat-to-target recommendations—three months for high and moderate disease activity patients and six months for low and controlled patients.

Bottom line, rheumatologists need an analytic disease registry to enroll all our patients and enter their disease activity measures and medications by dates to allow us to see our care gaps, and then we need to use this tool to manage our practice work and track our performance. Physicians lack the time and expertise to do this alone; it takes a team.

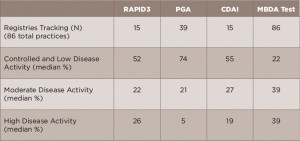

2. Assessing disease activity ourselves during office visits as we are used to doing precludes on-time disease activity assessments in busy practices.5 The more data we’ve collected, the more obvious this has become (see Table 1).6 The reasons include:

- Most importantly, we lack the numbers of physician-established patient visit slots required to see the numbers of RA patients we manage as often as the guidelines recommend based on their disease activity status.

- Controlled patients are too often taking up appointments to confirm that everything is going well at the same time as active patients aren’t being seen often enough to modify their treatments as recommended in the 2015 ACR guidelines.7

- We lack the time during scheduled visits to both assess patients accurately and to make necessary adjustments to their treatment, so those with active disease are often maintained on the same treatments. Moreover, if the patient presents with an urgent problem, disease assessment and management are often deferred.

- Finally, we see many high disease activity patients who cannot be treated more aggressively for one or more reasons—insurance denials, co-morbidities, patient preferences, etc. Such patients make up about 50% of those with high disease activity in typical RAPP practices.5

Bottom line: We’ve realized that current visit schedules and practice workflows create intractable care gaps and prevent physicians from doing the work that only we can do for new and established patients. We need clinical population management by care teams to see patients as often as necessary—and only as necessary.