3. Our validated composite RA disease activity measures tie up physicians’ time and, too often, confound clinical decision making. Initially, each RAPP participant continued using their disease activity measure(s) of choice. Most were variably using some combination of a RAPID3, a stratified physician global assessment (PGA), the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and a multi-biomarker disease activity (MBDA) test. A few were also using diagnostic ultrasound to assess inflammation and structural disease progression.8,9

As we accumulated disease activity measures from multiple practice populations, it became clear that different measures were indicating different disease activity levels for many patients. Physician global assessments indicated about 70% controlled and low and 30% moderate and high disease activity across multiple practices. MBDA tests showed the opposite, and the RAPID3 and CDAI distributions fell in between (see Table 2).10 How well we are managing our population depends most on which measure we choose as our population signal.

Bottom line: We need to not only improve how often we measure, but how we measure disease activity to make optimal treatment decisions, especially considering the recently described consequences of failing to control active disease.11

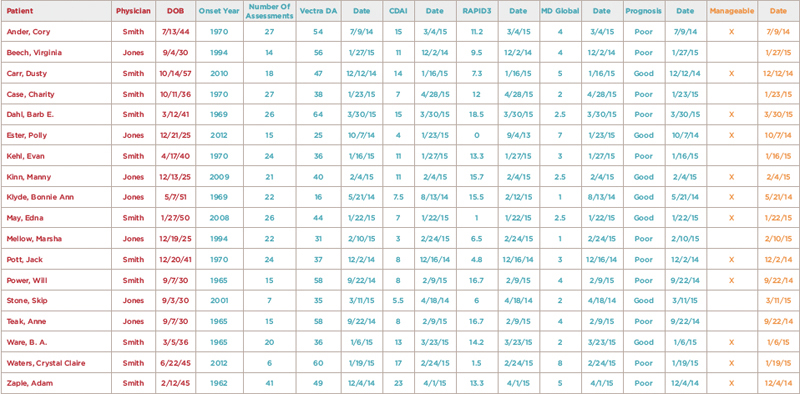

(click for larger image) Figure 1: Example Disease Registry Spreadsheet

Note: This spreadsheet includes patient and managing physician identifiers (red), information critical for disease management (teal), and whether each patient’s disease can be managed or not (orange). Each column can be sorted to stratify disease duration, disease activity, last assessment dates (on time and overdue), prognosis and manageability (yes or no). An individual patient’s accumulated assessments can be viewed separately and tracked to facilitate their individual treatments in most available disease registries.

Confront the Problems

Here’s what RAPP physicians are doing differently to address these critical practice problems:

- Maintaining disease population registries and using them to ensure on-time assessments. (These registries are our air traffic control systems.) Once we achieve this timeliness, attention can be focused on patients who need and are able to receive care. A team approach with dedicated registry managers is needed to make this happen. Several registry alternatives that provide these analytics are available to rheumatologists, and some richly resourced practices have built their own inside their HIPAA-protected IT environments.

- Performing disease assessments several weeks prior to physician disease management visits. Early breaking RAPP practices are eliminating their assessment and care gaps with this strategy. Patients who are well controlled or cannot be managed further are being scheduled for next assessment visits in six months rather than seeing the physician at all. This approach is increasing patient throughputs and panel sizes, and improving access to new patient consultations with the rheumatologist.

- Choosing a basket of disease activity measures to aid treatment decisions, and ultimately to inform more accurate decisions. Based on RAPP data, using clinical composites validated against the DAS28, as the ACR recommends, is highly suspect outside clinical trial populations.7 We need to keep exploring more objective, sensitive and feasible alternatives: MBDA tests and diagnostic ultrasound being two examples.12,13 RAPP physicians are grappling with the discordances between different disease activity measures, in part by expanding their use of diagnostic ultrasound.

- Tracking the percentages of our populations with high, moderate and low–controlled disease activity. Disease control is the primary measurable outcome of disease management and predicts better function, quality of life and longevity for our patients.11 High percentages of patients with continuing active disease, once recognized, are not acceptable.

- Documenting the impacts of these practice changes by monitoring access to care for new and established patients, on-time disease assessment percentages, patient throughputs and financial balance sheets. We must do this to make our specialty more competitive for trainees and to counter the external management of our care and reimbursements by payers and other administrators.

- Using these data to continuously redesign our care processes and teams and to sustain high performance. The goals are to free physicians to do the work that only we can do, provide necessary patient care on time and improve disease outcomes. Practices are diversifying their teams by including scribes, pharmacists, ultrasound technicians and nurse practitioners, rather than more rheumatologists. We hope that our doing things differently will also change our relationships with payers.

Conclusions

How rheumatologists provide care is our primary problem, and only we can fix it. Doing so requires fundamental practice changes and hard work. The care gaps and core problems we have identified appear to be nearly universal. Clinical population management offers fundamental practice redesigns from traditional care. Different practice environments have different resources and barriers, but most can implement clinical population management as we’ve defined it.