Gajus/shutterstock.com

In 2008, the American College of Rheumatology Workforce Study Advisory Group published a comprehensive rheumatology workforce analysis.1 It concluded:

Based on assessment of supply and demand under current scenarios, the demand for rheumatologists is expected to exceed supply in the coming decades. Strategies for the profession to adapt to this changing health care landscape include increasing the number of fellows each year, utilizing physician assistants and nurse practitioners in greater numbers, and improving practice efficiency.

Eight years later, our specialty faces the same intractable shortage. To put it simply, no number of additional rheumatologists can close our care, disease outcome and professional income gaps until we fundamentally change the way our practices function. We need to focus on improving the effectiveness, efficiency and profitability of rheumatic disease care and on redesigning our academic teaching programs to better prepare trainees for increasingly challenging real-world practice environments.

A Perspective Change

We can’t do better until we see it differently.

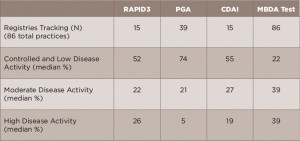

(click for larger image) Table 1: On-Time Assessment Rates*

*MBDA test data. Similar care gaps observed for other measures.

There have always been, and still are, exceptionally successful practices in rheumatology—and in other specialties managing chronic diseases.2 As a rule, however, rheumatologists provide physician-centric care one patient at a time, room to room, organized around each physician’s preferred appointment schedule. This is how we were taught, this is what we do, and this is what we have to change.

One exceptional rheumatologist and an ACR Master was Jacques Caldwell. He saw things differently: “I only do what only I can do.” His care teams saw 70+ patients a day and participated in many clinical trials, and yet his patients told him, “You are my only physician who has time for me when I need you.”3

From an income perspective, the ACR Workforce Study identified a minority of colleagues who take home two to three times the median rheumatology income.1 Unfortunately, income benchmarks for rheumatology are generally set at the median, potential trainees know these numbers, and we don’t compare favorably to other, more popular, specialties. What have these outliers figured out that the rest of us haven’t?

New Solutions Are Needed

The Rheumatoid Arthritis Practice Performance (RAPP) Project is a voluntary consortium of practicing rheumatologists founded in 2013 to improve our patient access, delivery of care and disease outcomes. Our primary focus is to provide accurate, on-time disease activity assessments and necessary treatments for our entire RA populations consistent with treat-to-target recommendations.4

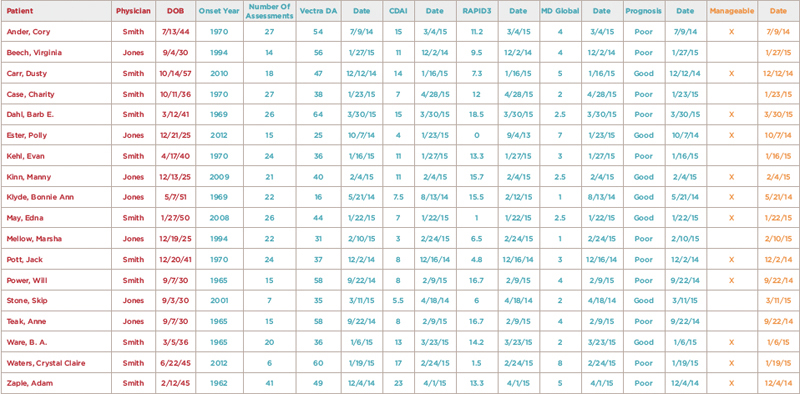

We are using iterative quality improvement methods to create effective care teams and using a simple HIPAA-compliant disease registry to enroll and track all our RA patients (see Figure 1, opposite). The registry data set includes patient and physician identifiers, year of onset, disease activity measures and medications by date, and whether individual patients’ management can be changed. These data are feasible for physicians and staff to collect and use in busy practice environments. All other data go into each patient’s medical record as usual.

We have labeled this different approach to care for chronic diseases Clinical Population Management. Project progress was shared at the 2014 and 2015 ACR/ARHP Annual Meetings and previously published in The Rheumatologist.5

Here’s what we’ve learned so far:

1. Managing chronic diseases without a disease population registry is like trying to manage O’Hare Airport without an air traffic control system: There are 600 planes up there somewhere, but you can only see the ones in sight and have no idea what’s going on with the rest. A disease population registry allowed us to understand for the first time how many RA patients we manage; who they are; when their disease activity was last assessed; who is overdue; what percentages have high, moderate, low and controlled disease; how we are treating them; and how well we are controlling their disease. Electronic health records generally don’t provide this information because each patient’s data are filed by encounters, and population analytics are missing.

The baseline RAPP practice registry data weren’t pretty.4 We had more RA patients (median 585) than we had thought, and our assessments were only on time for about 40% of our populations using minimum standards from the treat-to-target recommendations—three months for high and moderate disease activity patients and six months for low and controlled patients.

Bottom line, rheumatologists need an analytic disease registry to enroll all our patients and enter their disease activity measures and medications by dates to allow us to see our care gaps, and then we need to use this tool to manage our practice work and track our performance. Physicians lack the time and expertise to do this alone; it takes a team.

2. Assessing disease activity ourselves during office visits as we are used to doing precludes on-time disease activity assessments in busy practices.5 The more data we’ve collected, the more obvious this has become (see Table 1).6 The reasons include:

- Most importantly, we lack the numbers of physician-established patient visit slots required to see the numbers of RA patients we manage as often as the guidelines recommend based on their disease activity status.

- Controlled patients are too often taking up appointments to confirm that everything is going well at the same time as active patients aren’t being seen often enough to modify their treatments as recommended in the 2015 ACR guidelines.7

- We lack the time during scheduled visits to both assess patients accurately and to make necessary adjustments to their treatment, so those with active disease are often maintained on the same treatments. Moreover, if the patient presents with an urgent problem, disease assessment and management are often deferred.

- Finally, we see many high disease activity patients who cannot be treated more aggressively for one or more reasons—insurance denials, co-morbidities, patient preferences, etc. Such patients make up about 50% of those with high disease activity in typical RAPP practices.5

Bottom line: We’ve realized that current visit schedules and practice workflows create intractable care gaps and prevent physicians from doing the work that only we can do for new and established patients. We need clinical population management by care teams to see patients as often as necessary—and only as necessary.

3. Our validated composite RA disease activity measures tie up physicians’ time and, too often, confound clinical decision making. Initially, each RAPP participant continued using their disease activity measure(s) of choice. Most were variably using some combination of a RAPID3, a stratified physician global assessment (PGA), the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and a multi-biomarker disease activity (MBDA) test. A few were also using diagnostic ultrasound to assess inflammation and structural disease progression.8,9

As we accumulated disease activity measures from multiple practice populations, it became clear that different measures were indicating different disease activity levels for many patients. Physician global assessments indicated about 70% controlled and low and 30% moderate and high disease activity across multiple practices. MBDA tests showed the opposite, and the RAPID3 and CDAI distributions fell in between (see Table 2).10 How well we are managing our population depends most on which measure we choose as our population signal.

Bottom line: We need to not only improve how often we measure, but how we measure disease activity to make optimal treatment decisions, especially considering the recently described consequences of failing to control active disease.11

(click for larger image) Figure 1: Example Disease Registry Spreadsheet

Note: This spreadsheet includes patient and managing physician identifiers (red), information critical for disease management (teal), and whether each patient’s disease can be managed or not (orange). Each column can be sorted to stratify disease duration, disease activity, last assessment dates (on time and overdue), prognosis and manageability (yes or no). An individual patient’s accumulated assessments can be viewed separately and tracked to facilitate their individual treatments in most available disease registries.

Confront the Problems

Here’s what RAPP physicians are doing differently to address these critical practice problems:

- Maintaining disease population registries and using them to ensure on-time assessments. (These registries are our air traffic control systems.) Once we achieve this timeliness, attention can be focused on patients who need and are able to receive care. A team approach with dedicated registry managers is needed to make this happen. Several registry alternatives that provide these analytics are available to rheumatologists, and some richly resourced practices have built their own inside their HIPAA-protected IT environments.

- Performing disease assessments several weeks prior to physician disease management visits. Early breaking RAPP practices are eliminating their assessment and care gaps with this strategy. Patients who are well controlled or cannot be managed further are being scheduled for next assessment visits in six months rather than seeing the physician at all. This approach is increasing patient throughputs and panel sizes, and improving access to new patient consultations with the rheumatologist.

- Choosing a basket of disease activity measures to aid treatment decisions, and ultimately to inform more accurate decisions. Based on RAPP data, using clinical composites validated against the DAS28, as the ACR recommends, is highly suspect outside clinical trial populations.7 We need to keep exploring more objective, sensitive and feasible alternatives: MBDA tests and diagnostic ultrasound being two examples.12,13 RAPP physicians are grappling with the discordances between different disease activity measures, in part by expanding their use of diagnostic ultrasound.

- Tracking the percentages of our populations with high, moderate and low–controlled disease activity. Disease control is the primary measurable outcome of disease management and predicts better function, quality of life and longevity for our patients.11 High percentages of patients with continuing active disease, once recognized, are not acceptable.

- Documenting the impacts of these practice changes by monitoring access to care for new and established patients, on-time disease assessment percentages, patient throughputs and financial balance sheets. We must do this to make our specialty more competitive for trainees and to counter the external management of our care and reimbursements by payers and other administrators.

- Using these data to continuously redesign our care processes and teams and to sustain high performance. The goals are to free physicians to do the work that only we can do, provide necessary patient care on time and improve disease outcomes. Practices are diversifying their teams by including scribes, pharmacists, ultrasound technicians and nurse practitioners, rather than more rheumatologists. We hope that our doing things differently will also change our relationships with payers.

Conclusions

How rheumatologists provide care is our primary problem, and only we can fix it. Doing so requires fundamental practice changes and hard work. The care gaps and core problems we have identified appear to be nearly universal. Clinical population management offers fundamental practice redesigns from traditional care. Different practice environments have different resources and barriers, but most can implement clinical population management as we’ve defined it.

Drs. Erin and William Arnold, Sikes and Crump are clinician rheumatologists participating in the RAPP Project. Joiner Associates LLC, the RAPP Project coordinator, employed Dr. Harrington, Mr. Bower and Mr. Johnson.

References

- Deal CL, Hooker R, Harrington T, et al. The United States rheumatology workforce: Supply and demand 2005–2025. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Mar;56(3):722–729.

- Great Health Care: Making It Happen. Harrington JT, Newman ED, eds. New York: Springer USA, 2011.

- Personal communication.

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JWJ, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: Recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Apr;69(4):631–637.

- Arnold E, Arnold W, Conaway D, et al. Physician visits create a bottleneck in RA management. The Rheumatologist. 2015 Jun;9(6):44–46.

- Sikes D, Bower J, Johnson D, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis disease activity assessment frequencies in clinical practice do not support treat-to-target care [abstract 1027]. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Annual Meeting Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(suppl 10).

- Singh J, Saag K, Bridges S, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016 Jan;68(1):1–25.

- Sikes D, Crump G, Thomas K, et al. Population management of rheumatoid arthritis in rheumatology practices [abstract 1355]. 2014 American College of Rheumatology Annual Meeting. Arthritis Rheumatol.

- Winkler A, Mossell J, MacLaughlin E, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis disease activity assessment and population management processes used by clinician rheumatologists [abstract 1352]. 2014 American College of Rheumatology Annual Meeting. Arthritis Rheumatol.

- Crump G, Bower J, Foley T, et al. Different rheumatoid arthritis disease activity measures often provide discordant results in clinical practice populations [abstract 2317]. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Annual Meeting. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(suppl 10).

- Curtis J, Chen L, Kilgore M, et al. The clinical and economic costs of not achieving remission in rheumatoid arthritis [abstract 3183]. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Annual Meeting. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(suppl 10).

- Curtis JR, van der Helm-van der Mil AH, Knevel R, et al. Validation of a novel multibiomarker test to assess rheumatoid arthritis disease activity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 Dec;64(12):1794–1803.

- American College of Rheumatology Musculoskeletal Ultrasound Task Force. Ultrasound in American rheumatology practice: Report of the American College of Rheumatology musculoskeletal ultrasound task force. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010 Sep;62(9):1206–1219.

Disclosure

Joiner Associates received consulting fees from Crescendo Bioscience for designing and coordinating the project—without any influence from the company. Crescendo Bioscience has also provided support for participant advisory board meetings for this quality-improvement initiative and speaker honoraria to Drs. Arnold, Sikes and Crump. The participating clinician authors have reported no other individual disclosures.