GLENDALE, ARIZ.—Arizona is a microcosm of America’s challenges in reconciling the rheumatology workforce to growing patient demand, as quantified in the ACR’s Workforce Study of 2015.1 So it was timely this year for the Phoenix Rheumatology Association to sponsor its 1st Annual Strategic Training for Rheumatology Advanced Practice Clinicians Symposium. (Note: Advanced practice clinicians [APCs] is the preferred collective term for nurse practitioners [NPs] and physician assistants [PAs]).

Sixty-seven APCs from 22 states gathered in Glendale, Ariz., May 4–6, 2018, for a series of clinical lectures and more. Opening with an appraisal of the role that APCs play in helping close the current and evolving workforce gap, the curriculum included two interactive sessions orchestrated to begin building best practice concepts that may assist rheumatology practices with onboarding APCs and nurturing their careers in the field. The viewpoints and concerns of APCs, as well as qualitative and semi-quantitative information gathered in the symposium, may be of use to rheumatologists considering adding APCs to their operational structure.

The Workforce Shortage

Dr. Caldron presented data from the ACR Workforce Study at the 1st Annual Strategic Training for Rheumatology Advanced Practice Clinicians Symposium.

In brief, the current deficit of 700 rheumatologists in the U.S. will expand to 4,100 by 2030. The specialty can anticipate a decrease of 31% in workforce concomitant with an increase of 138% in demand for services. Among the cited forces working against the workforce are the opportunity costs of a career in the specialty, retirement of the baby boom generation, effects of the male to female workforce gender transition, return of international medical graduates to their home countries and fellowship graduates seeking less than full-time work.2

Rheumatology-filled training positions increased between 2012 and 2016, but the anticipated 107 full-time equivalents from current training programs fall woefully short of replacing the more than 200 projected annual retirements. In this milieu, the hoped-for remedy to supplement practices with APCs would establish a ratio of APCs to rheumatologists at 1:10.

One medical practice, Arizona Arthritis and Rheumatology Associates (AARA), that has tapped into this resource over nearly 25 years approaches a ratio of 2:1. A universal strategy of this kind may mitigate the deficit substantially.

Multiple organizations are involved in efforts to leverage this APC lifeline. The ACR maintains its modular online curriculum for allied health professions and provides a consensus-developed curriculum for the training of APCs. In March, it announced a grant in support of in-service training for individual APCs. The Rheumatology Nurses Society (RNS) provides symposia geared synchronously to APCs and infusion nursing staff. The composite of literature specific to APCs in rheumatology, although thin, generally affirms the specialty as a compatible and effective niche for these professionals.3-6

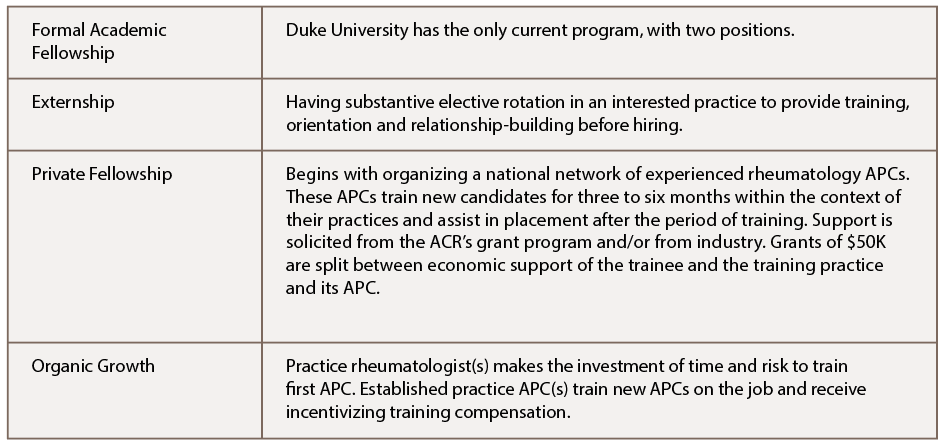

Didactic and clinical training in rheumatology occupies little space in the typical academic years for APCs. In contrast to multiple other medical, surgical and psychiatric disciplines in which 12-month fellowships are available to APCs, only Duke University offers a program for NP fellows in rheumatology. The fellowship, started in 2017, offers a place to two NP fellows. A successful PA fellowship in rheumatology at the Dallas Veteran’s Administration Medical Center ended when its four-year grant lapsed in 2008.7 Ultimately, most training of APCs in rheumatology is on the job and lacks uniformity.

Symposium Setup

Results of an administrative study at AARA that underscored the challenges of reaching competency and confidence in this complex specialty were discussed at the symposium. Views from this study on how APCs learn in didactic sessions and experience from the RNS guided the Phoenix Rheumatology Association to challenge both physician and APC lecturers to provide disease-oriented, highly functional lectures limited to 30 minutes followed by 15 minutes of panel Q&A.

The clinical lectures covered rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriatic arthritis, spondyloarthropathies, crystalline arthropathy, osteoarthritis and joint hypermobility, myositis, vasculitis, scleroderma, osteoporosis, fibromyalgia and the central sensitization syndrome.

An interactive lunch presentation placed participant APCs in the role of consultant in breaking down barriers for the rheumatologist contemplating the hiring, training and career development of an APC for the first time.

How would experienced APCs erode physician barriers that may center on trepidation about recruitment, on-the-job training and delegation, and financial risks?

Breaking Down the Barriers

Views and experiences on seeking new graduates diverged. Betsy Kirchner, NP, Cleveland Clinic, indicated that institution’s experience with new grads “has not been about the lack of experience; it is a sort of educational burnout. Rheumatology is about going home and reading a few chapters. … If the person who is being interviewed doesn’t seem to give you that sense that they would do that, then it is probably not going to work out,” she said.

Katherine Clark, PA-C, said, “When thinking of hiring an APC, precept a student from a PA school or an NP school … for six to eight weeks if you can. That way you get to know them and whether you fit well together, and they get to learn your practice. You are not paying them while you are training them. They then know how you practice and are able to begin working as your APC pretty smoothly that way.”

Nancy Eisenberger, an NP in southern New Jersey, suggested that experienced APCs participating in the symposium collaborate to organize a nationwide fellowship training program to develop new graduates and pay them a small stipend. The collaborative could then align them with practices who want an APC but would not take someone on without some specialty training.

Richard Horn, NP, who currently works alone, recalled that in the first three years of training with a rheumatologist, he saw only established patients. When he was invited to see new patients, he felt insecure, but then, he says, “I got fired up, like this is really interesting.” Only then did he discover the motivation to study hard on his own.

Another APC who is the first in his practice group, which has several rheumatologists, is not allowed to see new consults due to the administrator’s interpretation of incident-to regulation. The PA is concerned that patients perceive a “bait and switch” dynamic when the rheumatologist hands them off later.

This contrasts with the team model, in which new patient confidence in APCs may blossom when witnessing the APC efficiently stand and deliver the history and exam to the attending rheumatologist. See Table 1 for a short list of suggested training settings.

What to Look for in an APC

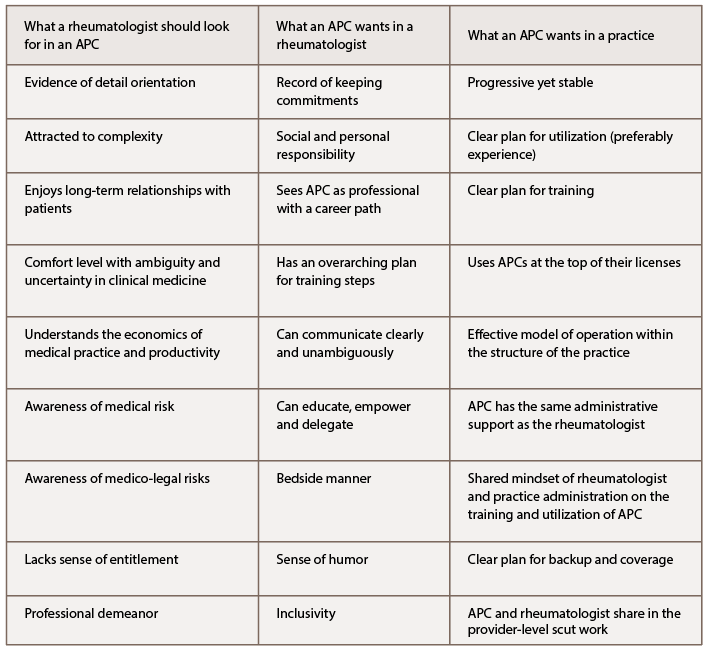

Participants sketched an abstraction of the successful APC in rheumatology. Characteristics that a rheumatologist should look for when selecting an APC may include evidence of being detail oriented and attracted to complexity. High marks in an APC’s didactic training and selection of rheumatology, hematology/oncology, endocrinology or similar cognitive specialties as electives could signal these attributes. Although top grades may not predict a variety of clinical skills, they may suggest an inclination to aggregate information systematically.

Does the candidate have a level of comfort with ambiguity and uncertainty (i.e., the ability to move ahead with decision making on incomplete information)? This essential talent in clinical rheumatology should be sought through discussion of a clinical case or two that the candidate recalls as particularly challenging and why.

The candidate’s attraction to long-term relationships with patients and interest in watching clinical stories unfold over time should be explored.

Competitive salary and production incentives are universally sought, but a candidate who spends more time wanting to hammer out a reasonable offer over asking about the nature of rheumatology, the practice environment and vision within the organization suggests short-sightedness and a sense of entitlement rather than work ethic.

Reviewing de-identified copies of the candidate’s prior history and physicals or consult notes may provide an impression of quality of documentation, consciousness of therapeutic risks and medico-legal awareness.

In common with any staffing decision, a candidate’s professional dress and mature demeanor throughout the interview process is a sine qua non for hire.

Lastly, family or personal experience in other businesses may convey an appreciation of the realities of sustaining a productive relationship.

What APCs Want in an Attending & a Practice

During the symposium, there was an even split in a participant show of hands: Half of the APCs in rheumatology sought out rheumatology as their target career, and half were just looking to get a job. Nonetheless, the rheumatologist should be aware of the attributes APCs find desirable in a rheumatologist and their practice organization.

Experienced rheumatology APCs agree that they look for evidence of personal and social responsibility and a record of keeping commitments. They say these are “foundational.” A love of teaching, an excellent bedside manner, a sense of humor and inclusive behavior are desirable. There should be a unified front presented by the supervising rheumatologist and practice administration on a well-defined plan for training and development, empowerment of the APC at the top of their license, involvement of the APC in the full spectrum of disease management and implementation of the methods of communication and operational interaction. These elements must be conveyed clearly and unambiguously.

Open dialogue on clinical matters and business matters should be the norm. Transparency with regard to salary, benefits and how production is tracked and rewarded is expected.

Of paramount importance to sustainability of the relationship of the APC with the rheumatologist and practice is that the APC be viewed as the professional they aspire to be.

Is the practice stable, yet progressive with regard to implementing newer technology, clinical research, student training and participation in databases? What was the turnover rate among staff in the past three years? Is there diversity among personnel? Is there goal congruity within the practice?

Working interviews in which an APC candidate who passes muster in an initial interview then shadows the rheumatologist (and any established APCs in the practice) mutually allow the APC to get a picture of the culture of the practice and the rheumatologist to probe the APC’s thought processes. During such activity, the APC may also gather clues about whether other personnel, such as RNs and licensed practical nurses, are working below their capabilities.

Ms. Kirchner believes that NPs, in particular, should take note of who is doing traditional nursing functions in the group, lest those tasks fall to the NP as well. Does the APC have administrative support equivalent to the rheumatologist, or would they be making all their own phone calls? Down the road, would flexibility exist in the operational sphere for the APC to model a schedule that sustains work-life balance, a flexibility that is highly desirable?

Hans Panwala, a PA-C from North Carolina, pointed out that rheumatologists should be aware that APCs must recertify based on general medical knowledge, so their educational time off and stipend may not all be spent on rheumatology gatherings.

How would rheumatologists interview effectively to select an APC? Katy Privon, an NP from Boise, Idaho, suggested adapting behavioral interviewing techniques, such as those used in Fortune 500 companies for managers and executives. “I think you really need to ask the hard questions … to find out if the person is really motivated to learn. New grads are often very eager. They don’t already have bad habits and are sometimes very moldable.” Table 2 provides a thumbnail compilation of the needs of the negotiating partners in the rheumatologist-APC dynamic.

‘When thinking of hiring an APC, precept a student from a PA school or an NP school … for six to eight weeks if you can. That way you get to know them & whether you fit well together, & they get to learn your practice.’ —Katherine Clark, PA-C

Salary & Benefits vs. Productivity

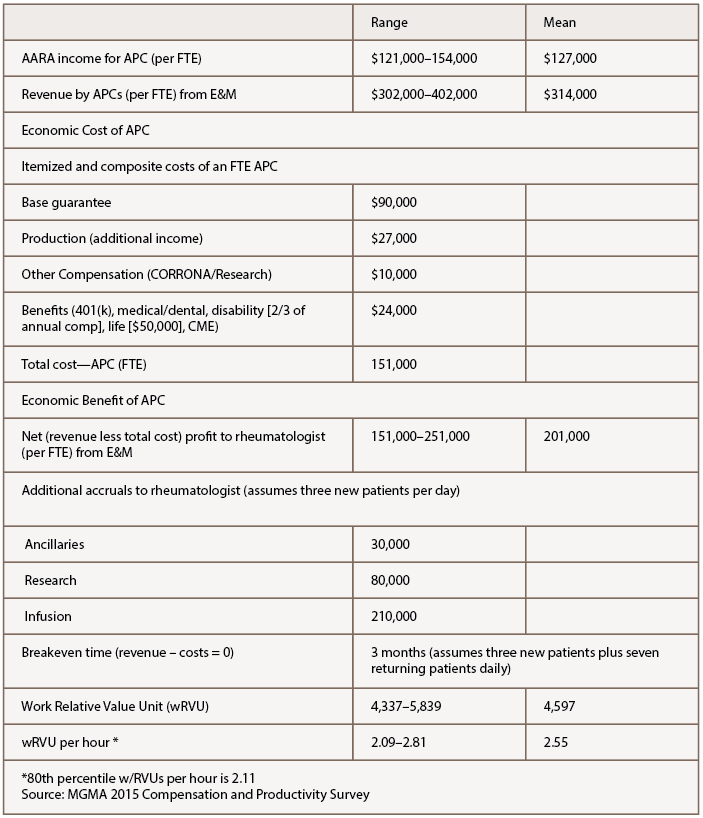

General salary data available from the Practice Match 2017 Nurse Practitioner and Physician Assistant Salary Survey for APCs indicate a bell curve in income from $75,000–150,000. The mean is $111,429, with variation depending on region and specialty. The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) provides an alternative way to measure productivity, using work relative value units (wRVUs), which appears to rapidly becoming an industry standard. According to the MGMA 2015 Compensation and Productivity Survey, at the 80th percentile, wRVU per hour is 2.11 for APCs.

Survey data specific to rheumatology APCs are not readily available. Calculations from AARA may not be representative of America’s rheumatology APC population but are available as an initial benchmark (see Table 3, p. 48). The income range for a full-time equivalent (FTE) APC in AARA is $121,000–154,000, mean $127,000. The mean total direct cost to the practice of $151,000 for the FTE APC is itemized in Table 3. Mean revenue generated by the FTE APC of $314,000 translates historically in 2017 to an accrual of mean $201,000 to the supervising rheumatologist’s accounting, minus any increase in fixed and labor costs attributable to the APC that could be extrapolated to approximately $10,000–20,000 annually.

The APC’s impact on other remunerative streams in the practice, such as ancillary services, infusion services and clinical research, are also estimable and substantive. Typically, the breakeven point of employment wherein APC revenues cover APC costs is three months in AARA’s operational model, seeing three new patients and seven return visits daily. Within that model, the mean wRVU per hour is 2.55.

Participants in the symposium commented that understanding how their earnings are calculated transparently, what costs are attributed to them and what they produce for the practice would provide a sense of control and lower anxiety about their financial relationship with their rheumatologists and their organizations. De-identified benchmarking to their peers in all calculations helps with goal setting.

Models

In another interactive session of the symposium, the prevalence of several rheumatology APC working models was evaluated. Five NPs in attendance were working without a rheumatologist where state laws allow independent practice.

Within the group setting, a show of hands placed most of the remaining participants split equally between a shared patient panel model with a specific rheumatologist and being responsible for their own panel of patients. One participant characterized her group of four rheumatologists and three APCs as successfully interacting in a loose fashion without any preset team structure.

In the AARA model, APC activities mimic permanent fellows in rheumatology. The model generally satisfies the professional aspirations of the APCs, functions well in economic terms, is embraced by patients and the referral base, and accrues a workforce for the community not otherwise achievable with the current dearth in new graduate rheumatologists.

Participants from other practices commented that in their practices, some physicians were happy to have APC associates while others were resistant or had no interest in their utilization. One APC intent on a full career in rheumatology expressed interest in practice ownership by APCs with physicians, a model for which there is precedent.

Play It Again

A near 50% post-symposium response gave the Phoenix Rheumatology Association a composite 93% approval on the clinical presentations, and 97% would like to repeat the program in 2019. Venues geared for rheumatology APCs have a future and should play a role in promoting the rheumatology APC identity and expansion. Advancing the exploratory ideas of these motivated colleagues through structured study of APC utilization, clinical training and professional development should leverage this opportunity to mind the gap.

Paul H. Caldron, DO, PhD, FACP, FACR, MBA, is a clinical associate professor at Midwestern University, Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine; a clinical assistant professor at the University of Arizona College of Medicine; and a practicing rheumatologist at Arizona Arthritis and Rheumatology Associates in Phoenix.

References

- Battafarano DF, Ditmyer M, Bolster MB, Fitzgerald JD, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Workforce Study: Supply and Demand Projections of Adult Rheumatology Workforce, 2015–2030. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018 Apr;70(4):617–626.

- Bolster M, Bass AR, Hausmann JS, Ditmyer M, Monrad S, Battafarano D. 2015 ACR/ARHP workforce study in the U.S.: The role of graduate medical education (GME) in adult rheumatology. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(suppl 10).

- Solomon DH, Bitton A, Fraenkel L, et al. Roles of nurse practitioners and physician assistants in rheumatology practices in the US. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014 Jul;66(7):1108–1113.

- Solomon DH, Fraenkel L, Lu B, Brown E, et al. Comparison of care provided in practices with nurse practitioners and physician assistants versus subspecialist physicians only: A cohort study of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015 Dec;67(12):1664–1670.

- Hooker R, Rangan B. Role delineation of rheumatology physician assistants. J Clin Rheumatol. 2008 Aug;14(4):202–205.

- Hooker RS. The extension of rheumatology services with physician assistants and nurse practitioners. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008 Jun;22(3):523–533.

- Hooker RS. A physician assistant rheumatology fellowship. JAAPA. 2013 Jun;26(6):49–50, 52.