Uveitis is an inflammation of the uvea, which comprises the iris, ciliary body and choroid. Uveitis can lead to ocular damage and complete visual loss.

Noninfectious etiologies for uveitis are the most common in the U.S.1 The estimated incidence of uveitis ranges from 25–52 per 100,000 in adults and five per 100,000 in children. The prevalence of uveitis ranges from 58–121 cases per 100,000 adults and 13–30 cases per 100,000 children.1-4

Pediatric patients present unique challenges for diagnosis and management.5 These challenges—difficult ophthalmic examinations, delayed diagnosis, medication side effects, adherence to treatment, risk of amblyopia and extended burden of disease into adulthood—require a multidisciplinary approach.6

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms of uveitis vary based on the anatomic location of the inflammation. Among pediatric uveitis cohorts, anterior uveitis is most common, with estimates ranging from 30–70% of total cases.5,7,8 Although usually asymptomatic, anterior uveitis can present with eye redness, pain, tearing and photophobia. In contrast, inflammation in the intermediate and posterior aspects of the uvea often presents with floaters and blurred vision.

In North America, juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common systemic disease associated with uveitis, and the condition occurs in 10–20% of children with JIA9-11 JIA-associated uveitis (JIA-U) is predominantly of the anterior uvea, affecting both eyes with non-granulomatous inflammation and characterized by a chronic and insidious course.12

Uveitis in the absence of known systemic disease is classified as idiopathic and is at least as common as JIA-U, with estimates ranging from 26–54% of all noninfectious uveitis cases.7,8,13,14 It can also be seen in other systemic inflammatory diseases, such as HLA-B27 disease, Behçet’s disease, sarcoidosis and vasculitides.15 Occasionally, patients may present with uveitis prior to developing systemic symptoms or signs.

Uveitis can lead to ocular complications, including cataracts, glaucoma, impaired visual acuity and blindness. These ocular complications appear in up to 50% of children affected. Despite advances in screening and treatment, vision loss (i.e., visual acuity of 20/50 or worse) occurs in 25–40%, and legal blindness (i.e., visual acuity of 20/200 or worse) in up to 25%.3,5,12,16-18

Guidelines for Uveitis Screening

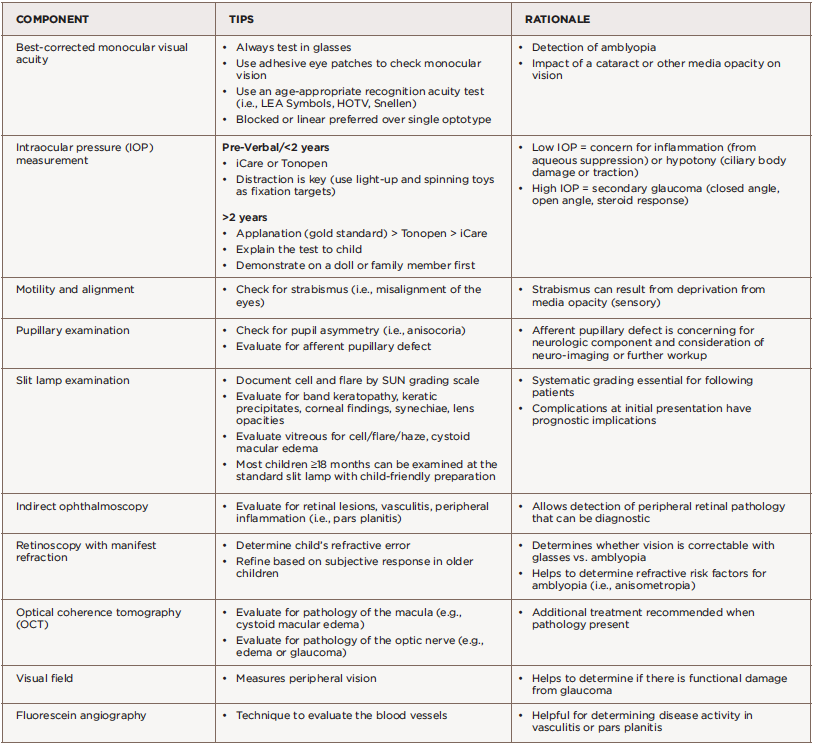

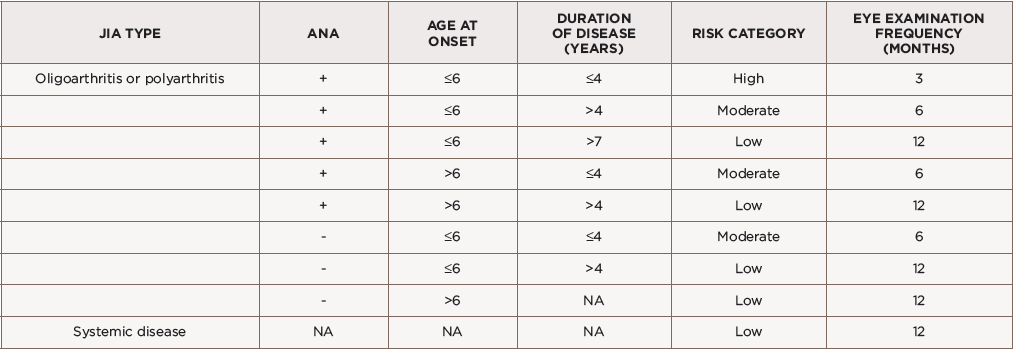

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) developed ophthalmology screening guidelines for children with arthritis because uveitis is typically asymptomatic in children (see Table 1).19 Screening intervals are based on risk factors, including articular features of disease (e.g., the category of JIA), anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) status, age at disease onset and disease duration.19,20 Children with oligoarticular or polyarticular rheumatoid factor (RF) negative JIA, with ANA positivity, who are younger than 7 years old at JIA onset and with a duration of JIA of four years or less are considered at high risk of developing uveitis—screen them every three months until they are 7 years old.18,20-23 Heiligenhaus et al. suggested including other JIA categories also at high risk for uveitis in the screening schedule (see Table 2).21

(click for larger image) Table 1: American Academy of Pediatrics Screening Guidelines for Children with JIA*

ANA = anti-nuclear antibodies; NA = not applicable

*Adapted from Cassidy et al., 2006.

On the other end of the spectrum, children with systemic or polyarticular rheumatoid factor (RF) positive JIA are considered at low risk, with less than 1% developing uveitis, and these patients can be screened every 12 months.20,21 Additional factors such as female sex, Caucasian race and non-Hispanic ethnicity have been associated with uveitis susceptibility and ocular complications, but these factors are not currently used in the screening guidelines.

(click for larger image) Table 2: Screening Recommendations in JIA Classified by International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) Criteria*

ANA = anti-nuclear antibodies; RF = rheumatoid factor; NA = not applicable

*Adapted from Heiligenhaus et al., 2007.

Once uveitis is diagnosed, the frequency of eye examinations is not standardized; it’s based on the patient’s response to therapy and ocular complications.20

Risk Factors

The slit lamp examination should include measurement of cell and flare by the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) and careful documentation of any complications of uveitis.

As with other autoimmune diseases, the etiology of uveitis is likely multifactorial. Children with HLA-DRB1 alleles have increased risk for uveitis.24-29 Studies have also investigated potential biomarkers in JIA-U, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), interleukin 29/interferon λ1 (IL29/IFNλ1), transthyretin (TTR) and other cytokines and chemokines.30-34 Identifying biomarkers that aid in screening, monitoring disease and treatment decisions may help improve outcomes in uveitis. Active research is underway to identify biomarkers in tears and aqueous humor associated with uveitis susceptibility, treatment response and ocular outcomes.

Various risk factors have been associated with ocular complications and visual impairment, including race, sex, ANA positivity and uveitis age and onset. African-American children have lower risk of JIA-U compared with non-Hispanic whites. However, if diagnosed, African Americans may be at higher risk for ocular complications and vision loss.35,36 Also, Hispanic ethnicity is associated with a higher rate of vision loss at baseline.5 Although females have an increased likelihood of uveitis, males may be more likely to have severe uveitis at diagnosis.22,37

ANA positivity has been associated with uveitis, but ANA-negative children may have increased complications.38 A short duration between the development of arthritis and subsequent diagnosis of uveitis, and a uveitis diagnosis at a young age, increase risk for severe ocular manifestations.12,22 Children who develop uveitis prior to arthritis diagnosis have increased rates of complications.38-40 This may be due to the asymptomatic presentation of uveitis associated with JIA leading to a delayed diagnosis.

Collaboration with Ophthalmology

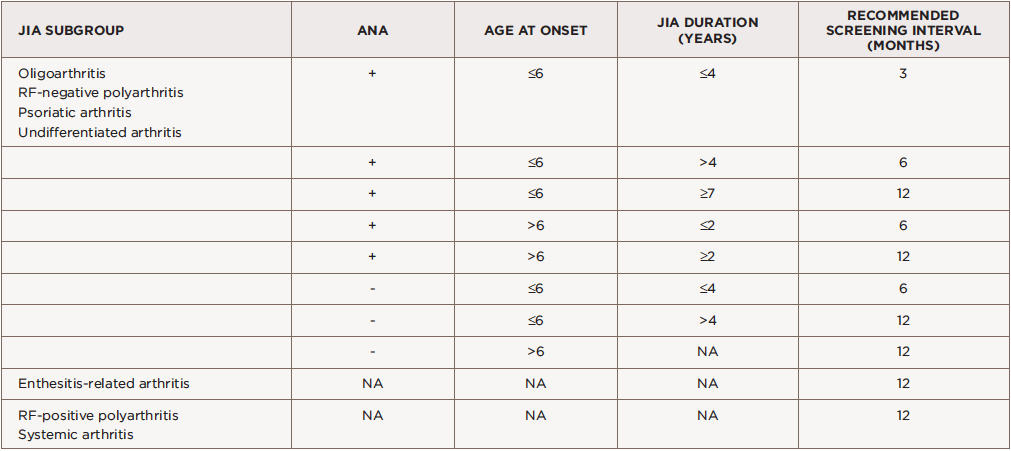

Pediatric uveitis management is challenging. Emphasize the importance of regular ophthalmology screening to families, given the asymptomatic nature of uveitis and risk for poor visual outcomes. The eye examination typically consists of measuring monocular best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), intraocular pressure (IOP), alignment and motility, anterior segment examination by slit lamp exam (prior to the instillation of any eye drops), and pupillary reaction (see Table 3). The slit lamp examination should include measurement of cell and flare by the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN), and careful documentation of any complications of uveitis.41

During the ophthalmology visit, the patient should be dilated for at least 30 minutes with cyclopentolate 1% and phenylephrine 2.5% drops for a detailed examination of the retina and measurement of refractive error. Measurement of refractive error when the pupils are dilated is essential in all children, especially those with reduced visual acuity, to determine whether vision changes are related to refractive error or amblyopia.

Amblyopia is decreased vision in one or both eyes due to abnormal visual stimulation of the brain in infancy or early childhood. Uveitis can cause amblyopia via changes in refractive error from lenticular changes, glaucoma or deprivation secondary to media opacities such as band keratopathy, cataract, vitreous opacities and cystoid macular edema. Ancillary testing by visual field test (to measure peripheral vision), optical coherence tomography (to measure the thickness of the optic nerve and macula), and fundus photography may be performed based on clinical examination findings. This testing can help monitor complications of uveitis, such as glaucoma or cystoid macular edema.

Close collaboration between the rheumatologist and ophthalmologist is essential to optimize outcomes for the patient. The ophthalmologist closely monitors ocular inflammation through slit lamp exam and manages topical and peri/intraocular ophthalmic medications. The rheumatologist diagnoses and manages associated systemic diseases and treatment with systemic immunosuppressive medications.42 Regular communication is also important in establishing an overall treatment plan for each patient.

Unfortunately, when these evaluations are performed through specialists practicing in different healthcare systems, formal reports may not always be communicated between providers, creating fragmented care and potentially delayed diagnosis and treatment. Combined ophthalmology-rheumatology clinics can address these concerns. A review over a three-year period from a combined pediatric ophthalmology and rheumatology clinic in Edinburgh, Scotland, suggested improved eye screening rates, improved convenience for both patients and providers, and prevention of delayed diagnosis and treatment in patients with uveitis present at their first eye exam.43

Our experience from the combined uveitis clinics at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio has shown the advantages of subspecialty collaboration. Our clinic is staffed by both a pediatric ophthalmologist and a pediatric rheumatologist who perform evaluations simultaneously, which leads to a unified approach to care. The ophthalmologist performs an extensive eye assessment to determine the presence and extent of inflammation, and the rheumatologist conducts a full physical exam to evaluate for associated systemic conditions. The specialists can learn from one another, make treatment decisions based on their combined assessment and educate patient and families in real time if systemic therapies are required.

Patients and families view such clinics favorably because they are convenient; decrease burdens associated with missed school and work days, transportation and childcare for other children; and allow clinical care decisions to be made during the appointment.

Psychosocial Aspects

Effective management of chronic diseases also requires an appreciation of how disease and complex treatment regimens impact a child’s daily functioning and quality of life (QOL). Uveitis and sight-threatening complications can significantly affect vision-specific functioning and QOL.44 Systemic immunosuppression and side effects, frequent and painful eye drops in the home and school, and recurrent visits with subspecialists can prove burdensome.

Most studies in pediatric uveitis focus on pathologic processes and outcomes, and place less emphasis on the child’s and family’s perspective on disease and treatment burden, as well as the effects of visual disability. Therefore, we developed the first uveitis-specific tool for children 5–18 years old that assesses vision-related function and QOL, “Effects of Youngsters’ Eyesight on Quality of Life” (EYE-Q). The EYE-Q questionnaire provides valuable insight into visual disability secondary to uveitis that is not generally measured by more general QOL instruments.45-47

Improvements in the assessment of the clinical significance of uveitis and the effects of visual impairment and treatment would improve disease management, visual outcomes and, importantly, QOL.

Summary

Uveitis is a chronic inflammatory eye disease that may lead to sight-threatening complications and significantly impact visual functioning and QOL among children with JIA. Known risk factors exist for uveitis and poor visual outcomes, but more work must be done to determine predictive biomarkers we can use clinically. Regularly scheduled ophthalmology screening in children with JIA and close monitoring in children diagnosed with uveitis are essential to maintain eye health. Close collaboration and communication between rheumatology and ophthalmology are crucial to improve visual outcomes. And future research is needed to elucidate clinical and genetic risk factors, biomarkers associated with uveitis susceptibility and visual outcomes, and the impact of disease and treatment on function and QOL.

Joseph McDonald, MD, is a pediatric rheumatology fellow at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. He completed his pediatric residency at the University of Cincinnati.

Virginia A. Miraldi Utz, MD, is an assistant professor of pediatric ophthalmology at the Abrahamson Pediatric Eye Institute at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. She is a pediatric ophthalmologist with subspecialty training and expertise in the field of ocular inflammation and uveitis.

Sheila T. Angeles-Han, MD, MS, is an associate professor of pediatrics at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and the University of Cincinnati. Dr. Han is a pediatric rheumatologist with a clinical and research interest in ocular inflammatory diseases.

Disclosures

Dr. McDonald has no potential conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Utz reports no support or research specific to this topic, but serves on the Pediatric Advisory Board for Spark Therapeutics, has received royalties for a textbook from Springer Publishing and has served as an unpaid investigator for Retrophin.

Dr. Angeles-Han developed the Effects of Youngsters’ Eyesight on Quality of Life (EYE-Q) tool, which has a license through Emory University. No royalties have been received by any of the authors. She is supported by Award No. K23EY021760 from the National Eye Institute, a grant from the Rheumatology Research Foundation and the CCHMC Research Innovation and Pilot Award.

References

- Thorne JE, Suhler E, Skup M, et al. Prevalence of noninfectious uveitis in the United States: A claims-based analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016 Nov 1;134(11):1237–1245.

- Acharya NR, Tham VM, Esterberg E, et al. Incidence and prevalence of uveitis: Results from the Pacific Ocular Inflammation Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013 Nov;131(11):1405–1412.

- Gregory AC, Kempen JH, Daniel E, et al. Risk factors for loss of visual acuity among patients with uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: The systemic immunosuppressive therapy for eye diseases study. Ophthalmology. 2013 Jan;120(1):186–192.

- Gritz DC, Wong IG. Incidence and prevalence of uveitis in Northern California: The Northern California Epidemiology of Uveitis Study. Ophthalmology. 2004 Mar;111(3):491–500.

- Smith JA, Mackensen F, Sen HN, et al. Epidemiology and course of disease in childhood uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2009 Aug;116(8):1544–1551.

- Holland GN, Stiehm ER. Special considerations in the evaluation and management of uveitis in children. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003 Jun;135(6):867–878.

- Edelsten C, Reddy MA, Stanford MR, et al. Visual loss associated with pediatric uveitis in english primary and referral centers. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003 May;135(5):676–680.

- Rosenberg KD, Feuer WJ, Davis JL. Ocular complications of pediatric uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2004 Dec;111(12):2299–2306.

- Nordal E, Rypdal V, Christoffersen T, et al. Incidence and predictors of uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a Nordic long-term cohort study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2017 Aug;15(1):66.

- BenEzra D, Cohen E, Behar-Cohen F. Uveitis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A cohort study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2007 Dec;1(4):513–518.

- Kanski JJ. Juvenile arthritis and uveitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1990 Jan–Feb;34(4):253–267.

- Sabri K, Saurenmann RK, Silverman ED, et al. Course, complications and outcome of juvenile arthritis-related uveitis. J AAPOS. 2008 Dec;12(6):539–545.

- Kump LI, Cervantes-Castañeda RA, Androudi SN, et al. Analysis of pediatric uveitis cases at a tertiary referral center. Ophthalmology. 2005 Jul;112(7):1287–1292.

- de Boer J, Wulffraat N, Rothova A. Visual loss in uveitis of childhood. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003 Jul;87(7):879–884.

- Kanski JJ, Shun-Shin GA. Systemic uveitis syndromes in childhood: An analysis of 340 cases. Ophthalmology. 1984 Oct;91(10):1247–1252.

- Angeles-Han ST, McCracken C, Yeh S, et al. Characteristics of a cohort of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and JIA-associated uveitis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2015 Jun 2;13:19.

- Holland GN, Denove CS, Yu F. Chronic anterior uveitis in children: Clinical characteristics and complications. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009 Apr;147(4):667–678.

- Woreta F, Thorne JE, Jabs DA, et al. Risk factors for ocular complications and poor visual acuity at presentation among patients with uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007 Apr;143(4):647–655.

- American Academy of Pediatrics section on rheumatology and section on ophthalmology: Guidelines for ophthalmologic examinations in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatrics. 1993 Aug;92(2):295–296.

- Cassidy J, Kivlin J, Lindsley C, et al. Ophthalmologic examinations in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatrics. 2006 May;117(5):1843–1845.

- Heiligenhaus A, Niewerth M, Ganser G, et al. Prevalence and complications of uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a population-based nation-wide study in Germany: Suggested modification of the current screening guidelines. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007 Jun;46(6):1015–1019.

- Chia A, Lee V, Graham EM, et al. Factors related to severe uveitis at diagnosis in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a screening program. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003 Jun;135(6):757–762.

- Edelsten C, Lee V, Bentley CR, et al. An evaluation of baseline risk factors predicting severity in juvenile idiopathic arthritis associated uveitis and other chronic anterior uveitis in early childhood. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002 Jan;86(1):51–56.

- Miller ML, Fraser PA, Jackson JM, et al. Inherited predisposition to iridocyclitis with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: Selectivity among HLA-DR5 haplotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Jun;81(11):3539–3542.

- Malagon C, Van Kerckhove C, Giannini EH, et al. The iridocyclitis of early onset pauciarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: Outcome in immunogenetically characterized patients. J Rheumatol. 1992 Jan;19(1):160–163.

- Melin-Aldana H, Giannini EH, Taylor J, et al. Human leukocyte antigen-DRB1*1104 in the chronic iridocyclitis of pauciarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Pediatr. 1992 Jul;121(1):56–60.

- Giannini EH, Malagon CN, Van Kerckhove C, et al. Longitudinal analysis of HLA associated risks for iridocyclitis in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1991 Sep;18(9):1394–1397.

- Glass D, Litvin D, Wallace K, et al. Early-onset pauciarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis associated with human leukocyte antigen-DRw5, iritis and antinuclear antibody. J Clin Invest. 1980 Sep;66(3):426–429.

- Angeles-Han ST, McCracken C, Yeh S, et al. HLA associations in a cohort of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis with and without uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015 Sep;56(10):6043–6048.

- Haasnoot AJ, van Tent-Hoeve M, Wulffraat NM, et al. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate as baseline predictor for the development of uveitis in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015 Feb;159(2):372–377.

- Haasnoot AJ, Kuiper JJ, Hiddingh S, et al. Ocular fluid analysis in children reveals interleukin-29/interferon-lambda1 as a biomarker for juvenile idiopathic arthritis associated uveitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 Jul;68(7):1769–1779.

- Kalinina AV, de Boer JH, Byers HL, et al. Intraocular biomarker identification in uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013 May 1;54(5):3709–3720.

- Sijssens KM, Rijkers GT, Rothova A, et al. Distinct cytokine patterns in the aqueous humor of children, adolescents and adults with uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2008 Sep–Oct;16(5):211–216.

- Walscheid K, Heiligenhaus A, Holzinger D, et al. Elevated S100A8/A9 and S100A12 serum levels reflect intraocular inflammation in juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis: Results from a pilot study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015 Dec;56(13):7653–7660.

- Angeles-Han ST, Pelajo CF, Vogler LB, et al. Risk markers of juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis in the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) registry. J Rheumatol. 2013 Dec;40(12):2088–2096.

- Angeles-Han ST, McCracken C, Yeh S, et al. The association of race with childhood uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015 Nov;160(5):919–928.

- Saurenmann RK, Levin AV, Feldman BM, et al. Risk factors for development of uveitis differ between girls and boys with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Jun;62(6):1824–1828.

- Chalom EC, Goldsmith DP, Koehler MA, et al. Prevalence and outcome of uveitis in a regional cohort of patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1997 Oct;24(10):2031–2034.

- Dana MR, Merayo-Lloves J, Schaumberg DA, et al. Visual outcomes prognosticators in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis-associated uveitis. Ophthalmology. 1997 Feb;104(2):236–244.

- Cabral DA, Petty RE, Malleson PN, et al. Visual prognosis in children with chronic anterior uveitis and arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1994 Dec;21(12):2370–2375.

- Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005 Sep;140(3):509–516.

- Smith JR, Rosenbaum JT. Management of uveitis: A rheumatologic perspective. Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Feb;46(2):309–318.

- Venkatesh P, Macrae M, Fleck BW. Lothian combined paediatric ophthalmology and rheumatology service. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006 Dec;90(12):1549–1550.

- Angeles-Han ST. Quality-of-life metrics in pediatric uveitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2015 Spring;55(2):93–101.

- Angeles-Han ST, Griffin KW, Harrison MJ, et al. Development of a vision-related quality of life instrument for children ages 8–18 years for use in juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011 Sep;63(9):1254–1261.

- Angeles-Han ST, Yeh S, McCracken C, et al. Using the effects of youngsters’ eyesight on quality of life questionnaire to measure visual outcomes in children with uveitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015 Nov;67(11):1513–1520.

- Angeles-Han ST, Griffin KW, Lehman TJ, et al. The importance of visual function in the quality of life of children with uveitis. J AAPOS. 2010 Apr;14(2):163–168.