It’s often said the eyes are the window to the soul, and in the case of ankylosing spondylitis and other spondyloarthropathies, one can also say the eyes are the window to systemic disease. Although uveitis occurs in approximately 2–5% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease, 6–9% of patients with psoriatic arthritis and 25% of patients with reactive arthritis, the prevalence may be as high as 33% in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.1

It’s often said the eyes are the window to the soul, and in the case of ankylosing spondylitis and other spondyloarthropathies, one can also say the eyes are the window to systemic disease. Although uveitis occurs in approximately 2–5% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease, 6–9% of patients with psoriatic arthritis and 25% of patients with reactive arthritis, the prevalence may be as high as 33% in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.1

Jennifer E. Thorne, MD, PhD, is the Cross Family Professor of Ophthalmology and chief of the Division of Ocular Immunology at the Wilmer Eye Institute at Johns Hopkins University, and professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore. In her practice, she evaluates and cares for patients with uveitis and other immune-mediated disorders of the eye, and her insights into diagnosing and treating these conditions provide a great deal of guidance to rheumatologists as they care for their patients.

Dr. Thorne notes that, based on the anatomic site of the primary inflammation, uveitis can be categorized into four subtypes:

- Anterior uveitis, in which the primary inflammation is in the anterior chamber;

- Intermediate uveitis, in which the primary source of inflammation is found in the vitreous body;

- Posterior uveitis, in which the primary source of inflammation is in the retina and/or choroid; and

- Panuveitis, in which the intraocular inflammation is equally distributed in the anterior chamber, vitreous and retina/choroid.

The location of inflammation affects the differential diagnosis. For example, anterior uveitis may be seen in association with spondyloarthritis and other rheumatologic conditions, but posterior uveitis may be due to a primarily ophthalmologic syndrome, such as the white dot syndromes, a group of inflammatory chorioretinopathies of unknown etiology.2

Importance of Screening

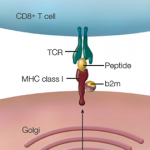

Once a patient presents with uveitis, it is important to screen for signs and symptoms of possible underlying infection, autoimmune or inflammatory disorder and malignancies, to name just a few of the conditions that can result in a secondary uveitis. Testing for human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27) is an important step in the evaluation of patients with uveitis. Among patients with ankylosing spondylitis, strong evidence suggests that positive HLA-B27 status is a risk factor for the development of uveitis, as may be the case for presence of hip-joint lesions on imaging, number of involved peripheral arthritic joints, increased antistreptolysin O titers, and increased circulating immune complex levels.3

Spondyloarthropathy Underdiagnosed

Several studies have sought to screen patients with uveitis for the possibility of an underlying spondyloarthritis. In the SENTINEL study, conducted by researchers in Spain, 798 consecutive patients with more than one episode of anterior uveitis separated by at least three months were prospectively evaluated with a series of clinic appointments with an ophthalmologist and a rheumatologist.4