It’s often said the eyes are the window to the soul, and in the case of ankylosing spondylitis and other spondyloarthropathies, one can also say the eyes are the window to systemic disease. Although uveitis occurs in approximately 2–5% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease, 6–9% of patients with psoriatic arthritis and 25% of patients with reactive arthritis, the prevalence may be as high as 33% in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.1

It’s often said the eyes are the window to the soul, and in the case of ankylosing spondylitis and other spondyloarthropathies, one can also say the eyes are the window to systemic disease. Although uveitis occurs in approximately 2–5% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease, 6–9% of patients with psoriatic arthritis and 25% of patients with reactive arthritis, the prevalence may be as high as 33% in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.1

Jennifer E. Thorne, MD, PhD, is the Cross Family Professor of Ophthalmology and chief of the Division of Ocular Immunology at the Wilmer Eye Institute at Johns Hopkins University, and professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore. In her practice, she evaluates and cares for patients with uveitis and other immune-mediated disorders of the eye, and her insights into diagnosing and treating these conditions provide a great deal of guidance to rheumatologists as they care for their patients.

Dr. Thorne notes that, based on the anatomic site of the primary inflammation, uveitis can be categorized into four subtypes:

- Anterior uveitis, in which the primary inflammation is in the anterior chamber;

- Intermediate uveitis, in which the primary source of inflammation is found in the vitreous body;

- Posterior uveitis, in which the primary source of inflammation is in the retina and/or choroid; and

- Panuveitis, in which the intraocular inflammation is equally distributed in the anterior chamber, vitreous and retina/choroid.

The location of inflammation affects the differential diagnosis. For example, anterior uveitis may be seen in association with spondyloarthritis and other rheumatologic conditions, but posterior uveitis may be due to a primarily ophthalmologic syndrome, such as the white dot syndromes, a group of inflammatory chorioretinopathies of unknown etiology.2

Importance of Screening

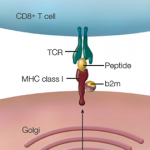

Once a patient presents with uveitis, it is important to screen for signs and symptoms of possible underlying infection, autoimmune or inflammatory disorder and malignancies, to name just a few of the conditions that can result in a secondary uveitis. Testing for human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27) is an important step in the evaluation of patients with uveitis. Among patients with ankylosing spondylitis, strong evidence suggests that positive HLA-B27 status is a risk factor for the development of uveitis, as may be the case for presence of hip-joint lesions on imaging, number of involved peripheral arthritic joints, increased antistreptolysin O titers, and increased circulating immune complex levels.3

Spondyloarthropathy Underdiagnosed

Several studies have sought to screen patients with uveitis for the possibility of an underlying spondyloarthritis. In the SENTINEL study, conducted by researchers in Spain, 798 consecutive patients with more than one episode of anterior uveitis separated by at least three months were prospectively evaluated with a series of clinic appointments with an ophthalmologist and a rheumatologist.4

In this cohort, 50.2% of patients were found to have an axial spondyloarthritis and 17.5% of patients had a peripheral spondyloarthritis, based on Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society criteria; the prevalence of spondyloarthritis was even higher among HLA-B27-positive patients than HLA-B27-negative patients (69.8% vs. 27.3% with axial disease, 21.9% vs. 11.1% with peripheral disease, respectively). The authors noted that numerous patients with anterior uveitis are likely to have undiagnosed spondyloarthritis and should be screened for these conditions.

The prevalence of uveitis may be as high as 33% in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Similarly, researchers from Dublin, Ireland, recruited 104 consecutive patients with presumed idiopathic acute anterior uveitis who presented to the ophthalmology emergency department over the course of one year.5 These patients each underwent a standardized evaluation that included testing for HLA-B27; clinical screening for symptoms and signs of axial or peripheral arthritis or enthesitis; personal or family history of psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease or other spondyloarthropathy; and radiographs of the sacroiliac joints and other joints as clinically indicated. Using this algorithm, 41.6% of the patients were found to have undiagnosed spondyloarthropathy, and this algorithm (termed the Dublin Uveitis Evaluation Tool) has now been validated as an instrument to assist first-line clinicians in recommending appropriate referral of uveitis patients to rheumatology clinics.

Screening for HLA-B27

In her own practice, Dr. Thorne makes sure to diligently screen for HLA-B27 status and for signs of conditions like ankylosing spondylitis, while also evaluating for diseases that include syphilis, tuberculosis, Lyme disease, sarcoidosis and other causes of uveitis. The one point Dr. Thorne stresses for rheumatologists: It is essential to counsel ankylosing spondylitis and other spondyloarthritis patients early and often that it’s critical to report any visual symptoms to allow for early ophthalmologic evaluation.

Any spondyloarthritis patient with a red and/or painful eye, new onset of blurry vision, sensation of flashing lights or floaters should be seen quickly by an ophthalmologist, who can perform a slit-lamp examination and evaluate for uveitis. Failure to arrange for this early evaluation can result in misdiagnosis and prolonged or recurrent symptoms for patients, causing them needless suffering.

Close Coordination of Care Necessary

First-line treatment for uveitis typically includes topical or injectable corticosteroids, but the severity of disease and frequency of recurrence will dictate if additional treatments are needed. These treatments may include oral corticosteroids, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil and, if necessary, the addition of biologic treatments, such as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, anti-interleukin 6 agents, calcineurin inhibitors and B cell depleting agents, such as rituximab. Close coordination of care is needed between ophthalmologists and rheumatologists to effectively treat the disease, monitor for medication side effects and long-term adverse effects, and ensure patients feel supported with regard to all manifestations of their systemic disease.

Even as some patients will experience more significant joint than eye symptoms over the course of their disease, others may have refractory uveitis despite quiescence of their musculoskeletal symptoms, thus communication between providers is imperative. Collaboration between practitioners in ophthalmology and rheumatology is needed now more than ever.6

The future has the potential to be quite bright for these patients, but only if the channels of communication are kept open and rheumatologists and ophthalmologists alike remain clear-eyed about the importance of recognizing and treating uveitis and its underlying causes.

Jason Liebowitz, MD, completed his fellowship in rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, where he also earned his MD. He is currently in practice with Arthritis, Rheumatic, & Back Disease Associates, New Jersey.

Jason Liebowitz, MD, completed his fellowship in rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, where he also earned his MD. He is currently in practice with Arthritis, Rheumatic, & Back Disease Associates, New Jersey.

References

- Sharma SM, Jackson D. Uveitis and spondyloarthropathies. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017 Dec;31(6):846–862.

- Crawford CM, Igboeli O. A review of the inflammatory chorioretinopathies: The white dot syndromes. ISRN Inflamm. 2013 Oct 31;2013:783190.

- Sun L, Wu R, Xue Q, et al. Risk factors of uveitis in ankylosing spondylitis: An observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Jul;95(28):e4233.

- Juanola X, Loza Santamaria E, Cordero-Coma M, et al. Description and prevalence of spondyloarthritis in patients with anterior uveitis: The SENTINEL interdisciplinary collaborative project. Ophthalmology. 2016 Aug;123(8):1632[PF4] –1636.

- Haroon M, O’Rourke M, Ramasamy P, et al. A novel evidence-based detection of undiagnosed spondyloarthritis in patients presenting with acute anterior uveitis: the DUET (Dublin Uveitis Evaluation Tool). Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Nov;74(11):1990–1995.

- Angeles-Han ST, Ringold S, Beukelman T, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the screening, monitoring, and treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019 Jun;71(6):703–716. Epub 2019 Apr 25. Simultaneously published by Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:864–877.