Since the mid-1980s, antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies and their associated clinical manifestations have attracted great interest among clinicians and investigators. Indeed, the attention directed to aPL often exceeds that for other autoantibodies within the field of autoimmunity. Even in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which is characterized by a multitude of specificities, the interest in this serological system remains high. The lupus anticoagulant (LAC) was first recognized more than 60 years ago, and its association with thrombosis and fetal loss was described in the mid-1970s.1-3 A dramatic boost in clinical interest came with the introduction of the anticardiolipin (aCL) test and subsequent efforts to link this test, as well as the LAC test, to a “new” condition, namely, antiphospholipid syndrome (APS).

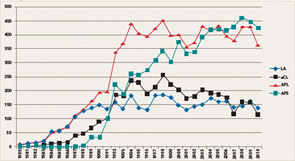

If the number of publications that use the keywords lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies, and antiphospholipid syndrome represents a measure of scientific interest, it is evident that an exponential increase in publications on these subjects began between 1984 and 1988 (see Figure 1). Indeed, investigators involved in the early phases of this work in the 1980s might be amazed today because, nearly three decades later, aPL antibodies and APS continue to attract a robust literature. Even if the number of publications may be showing a plateau, the high annual scientific output is impressive.

There are several reasons for the sustained interest in APS:

- The field has attracted clinicians and investigators from many disciplines, including rheumatology, hematology, obstetrics and gynecology, neurology, dermatology, and immunology.

- APS can have devastating and long-term debilitating consequences and usually affects otherwise healthy young individuals, particularly women.

- Beginning in the early 1990s, the development of in vivo mouse models, supported by in vitro studies, provided compelling evidence for a role of these antibodies in thrombosis, pregnancy loss, and thrombocytopenia.4-6

- APS is a multisystem disease, and several new pathogenic mechanisms have recently emerged to ignite interest in basic and translational research.

- Subclassification of the disorder and identifying its “true” clinical features based on solid evidence remains difficult.

- The optimal management of aPL antibody–related clinical manifestations, in particular, thrombosis and recurrent pregnancy loss, remains controversial.

- Importantly, testing for the various antibodies associated with APS has been the source of much controversy, particularly regarding the performance of different tests, measurement of antibody levels, and the extent of association of any serological finding with the various disease manifestations.

This article will summarize current data on traditional or “criteria” aPL antibody testing and discuss emerging assay methodologies and technologies. Our aim is to provide meaningful and accessible information so that practitioners understand the meaning of serological and functional tests, and to guide rheumatologists and other clinicians in their thinking as they face the challenge of diagnosing and managing patients suspected of having APS.

Criteria aPL Tests

Current classification criteria for definite APS require the use of three “standardized” laboratory assays to detect aPL. These assays include aCL, both immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgM; anti-β2glycoprotein I (anti-β2GPI) antibodies IgG and IgM; and/or LAC.7 These tests, when positive, represent criteria for diagnosis when at least one of the two major clinical manifestations (thrombosis or pregnancy losses) is present, according to the revised Sapporo criteria (see Table 1). Laboratory testing for aPL antibodies is one of the most problematic areas in the field of APS. The confirmation of diagnosis of the APS relies on laboratory tests because clinical manifestations such as thrombosis and pregnancy losses may occur for many reasons not related to the presence of aPL antibodies. Most important, patients with APS who have experienced thrombosis and/or pregnancy loss need a specific therapy that is often lifelong and must be personalized, requiring careful monitoring of additional risk factors to prevent recurrences of APS manifestations. Given the potential serious side effects of anticoagulant therapy, a solid diagnosis is essential in planning management.