Can we be sure that we do more good than harm when treating our inflammatory arthritis patients with biologic agents? This question may seem out of date today, but it was quite relevant 10 years ago following the introduction of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–α inhibiting agents. However, worries and uncertainty persist today regarding specific risks of these medications, particularly malignancy risk. If nothing else, the name tumor necrosis factor ties this cytokine to malignancy and suggests vigilance in its long-term use.

Let us look back a decade, to when the first TNF inhibitors came onto the market. At that time, the rheumatologic societies of several European countries felt that it was their responsibility to monitor the long-term safety of patients treated with a class of “experimental” agents. This decision sparked the creation of a number of epidemiologic drug registries, which were sponsored by unconditional grants from the companies that produced the biologic agents. Inherently, this registry design was a new concept and a landmark for drug research. The registries were independent studies supported jointly by several companies; these companies were all competing for market share but had no say in the design, conduct, or publication of the resulting data. Using this type of study, it was possible to obtain vitally needed long-term safety data in a time when public money was not available or could not be guaranteed for the duration of these studies.

Why Be Concerned?

The use of TNF inhibitors in rheumatology traces back to the identification of TNF-α as a key player in the cytokine network and a master regulator of inflammation. Even earlier, however, this cytokine had been identified as the “serum factor that causes necrosis of tumors.” This activity led to its name, which has remained, although other cytokines are identified by other terminologies, such as interleukin-1. Carswell et al first isolated TNF in 1975.1 Their research was inspired by the work of William Coley who, 82 years prior, had described the phenomenon of rapid tumor regression when he treated patients with filtrates from bacterial cultures.2

The concern with using TNF inhibitors was driven by the fact that the inflammatory cascade was disrupted by these agents with unknown long-term effects. On the other hand, as evidenced by the extensive research into the role of TNF in tumor biology, it was (and still is) uncertain whether TNF has pro- or antiproliferative actions on cells in a way that can impact malignancy in the clinical setting.

The major concerns regarding the relationship between TNF inhibition and cancer were underscored by two meta-analyses of early clinical trials, both of which showed a markedly increased risk for malignancy with the use of the monoclonal antibodies infliximab and adalimumab (pooled OR 3.3 [95% CI 1.2–9.1]) and a trend toward an increased risk for the fusion protein etanercept (HR 1.84 [95% CI 0.79–4.28]) compared with the placebo control group.3,4 The risk was shown to be greatest in patients taking infliximab or adalimumab at doses higher than those typically used in clinical practice; there was no significantly increased risk at lower doses of these drugs.5

As shown repeatedly, randomized clinical trials are insufficient instruments to assess the safety of drugs.6,7 Trials focus on a highly selected group of patients: only one-third of patients treated in practice would meet the inclusion criteria of most major clinical trials. In addition, trials study a small number of cases and use short observation periods. These shortcomings limit their ability to be extrapolated for use in clinical practice, and it makes one hesitant to place too much confidence in results on safety, especially in studies with negative results.

What options do we have for assessing the postmarketing safety of medical treatments?

In nearly all countries, there is a long tradition of spontaneous reporting to the health authorities of unexpected, serious adverse events. However, this form of data collection is susceptible to reporting bias, reflecting the prescribing physicians’ level of uncertainty regarding the safety of new agents. Nevertheless, spontaneous reporting systems are valuable for generating safety signals, although these signals need verification through appropriate cohort studies, in which patients are followed from the onset of exposure to the outcome. This approach would require a known denominator, a defined observation period, an adequate control population, and complete ascertainment of adverse events.

Biologics registries that adhere to these standards have been established in several countries. Moreover, some northern European countries have the capability of linking their data to other national registries, which allows for complete coverage of outcomes (e.g., cancer or death).

Within the last year, three large European registries have published new data on the occurrence of solid malignancies during treatment with TNF inhibitors, describing the incidence and the recurrence rates of tumors. We think it is worthwhile to look at the common messages these data convey.

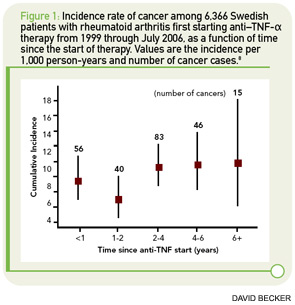

In Arthritis & Rheumatism, Askling et al reported on solid malignancies with data from the Swedish biologics registry ARTIS (See Figure 1, p. 34).8 The researchers linked data from ARTIS with population-based hospitalization and outpatient registries, as well as with the national cancer registry. A total of 67,743 rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients were available as controls for the 6,366 RA patients treated with biologic agents. Because the reporting of incident malignancies in the cancer registry has been mandatory in Sweden since 1958, the investigators were able to identify each incident cancer in their biologics cohort. The total observation time in the ARTIS cohort was 25,693 person-years of follow-up (mean, 3.9 years).

The overall incidence of cancer was 9.3 per 1,000 patient-years of follow-up in the ARTIS cohort of patients treated with biologic agents. The relative risks of cancer were 1.14 (95% CI 1.00–1.30) compared with the general population, 0.99 (95% CI 0.79–1.24) compared with patients starting on methotrexate, and 0.97 (95% CI 0.69–1.36) compared with patients starting nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) combination therapy. The incidence and relative risk of cancer did not change with observation time. Furthermore, the results were consistent, irrespective of the use of “time since initiation” of anti-TNF therapy or “cumulative duration of anti-TNF therapy” in the analysis.

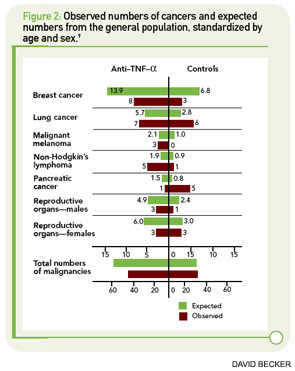

In January 2010, data were published regarding the German biologics registry RABBIT. These data focused on incidences and recurrence rates of malignancies in patients treated with TNF inhibitors compared with other agents (See Figure 2, p. 35).9 For incident tumors, the rates per 1,000 patient-years were 8.4 in patients treated with conventional DMARDs and 5.1 in patients treated with TNF inhibitors. Using a nested case-control approach, there was no difference in exposure to biologic agents between patients who developed cancer and those who did not.

Taken together, these results are reassuring regarding the risk of new malignancies facing patients treated with TNF-inhibiting agents. They confirm data from the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases, which showed no overall increase in the risk of solid malignancies in patients treated with biologic agents.10

In addition to the risk of a first cancer, another crucial clinical question is whether we can use TNF inhibitors to treat patients with a history of malignancy and, if so, how long we should wait after treatment of the first tumor to initiate anti-TNF treatment. Both the German and the British registries addressed this issue. Of 3,260 patients treated with TNF inhibitors in the German registry, 1.8% had a prior tumor compared with 3.1% of the 1,774 patients treated with nonbiologic DMARDs alone. This difference likely reflects the rheumatologists’ reluctance in prescribing TNF inhibitors to this patient population. The rates of recurrence of a new tumor were 45.5 per 1,000 patient-years with TNF inhibitors and 31.4 with nonbiologic DMARDs. This corresponds with a nonsignificantly elevated recurrence rate ratio of 1.4 (p = 0.6). The median time span between the prior tumor and inclusion in the registry (and start of either anti-TNF or DMARD therapy) was four years (IQR 2–10) in the group treated with TNF inhibitors and five years (IQR 3–11) in the nonbiologic DMARD-treated group.

If nothing else, the name tumor necrosis factor ties this cytokine to malignancy and suggests vigilance in its long-term use.

Although the German data could not rule out an increased recurrence risk with use of TNF inhibitors, recent data from the British Society of Rheumatology Biologics Register (BSRBR) are more reassuring.11 In the BSRBR, 177 patients treated with TNF inhibitors and 117 patients treated with DMARDs had a prior malignancy, diagnosed with a mean time of 11.5 years (TNF inhibitors) and 8.5 years (nonbiologic DMARDs) before inclusion in the registry. The recurrence rate was 25.3 per 1,000 patient-years in the TNF inhibitor group and 38.3 for DMARD-treated patients. These data supported an even lower risk of recurrence for patients treated with TNF inhibitors. Nevertheless, this registry also found that only 1.6% of all patients treated with TNF-inhibiting agents had a prior malignancy, compared with 3.6% of patients treated with nonbiologic DMARDs. This information, along with the relatively long duration of greater than 10 years before prescribing TNF inhibitors, suggests that physicians selected the patients treated with TNF inhibitors carefully. The lower recurrence rate in the anti-TNF treatment group might only reflect that this selection process was appropriate, and the results therefore cannot be generalized to all patients with prior malignancies.

Data on the risk of cancer recurrence are of greatest clinical importance because there likely will never be a clinical trial randomizing patients with prior malignancies to different treatment groups. Nevertheless, in daily practice, these patients need adequate treatment for their rheumatologic disease. The only option for answering such clinical questions is careful, long-term observation.

So Are We Safe Now?

Today, we have more evidence regarding the safety of TNF inhibitors and the risk of malignancy than we have ever had for any other immunosuppressive therapy. Although the data are reassuring, important unanswered questions remain. Our knowledge is still restricted to patients for whom rheumatologists have made careful decisions regarding the use of new treatments. Additionally, even if we are confident as to the overall risk of cancer, we do not know enough about site-specific tumor risks.

Patients with very active disease may be willing to accept a potentially and insignificantly increased risk of recurrence for the sake of adequate treatment of RA.

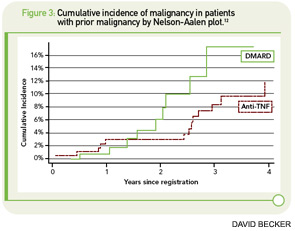

There is growing evidence of an increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in patients treated with TNF inhibitors. In 2007, Wolfe et al published cancer rates of about 13,000 patients with RA, of whom 49% were exposed to biologic agents.10 Although there was no overall increased risk for all cancers in patients treated with biologics, these agents were associated with an increased risk of NMSC (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.2–1.8) and melanoma (OR 2.3, 95% CI 0.9–5.4). At the ACR Annual Scientific Meeting in 2009, Mercer et al reported on NMSC from the BSRBR.12 In 11,757 patients exposed to TNF inhibitors and 3,515 patients exposed to DMARDs, the overall risk for NMSC was 5.1 per 1,000 patient-years for patients not exposed to TNF inhibitors and 4.5 for those with a history of exposure (See Figure 3, p. 35). However, prior NMSC was a strong predictor of incident skin cancer, with a relative risk of 9.8, compared with patients without prior NMSC. In addition, patients with prior malignancies were less likely to receive biologic therapy. In those patients with no history of NMSC, the risk per 1,000 patient-years was 2.4 for DMARD patients and 3.5 for those treated with TNF-α inhibitors, which corresponds with a 70% increased risk.

An additional concern is the potential increased risk for cancer in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) who are treated with TNF inhibitors. In the summer of 2009, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration released new safety information based on an analysis of 48 malignancies in children and adolescents treated with TNF inhibitors, and it required the manufacturers of TNF blockers to update the boxed warning in the prescribing information.13 Approximately half of the malignancies were lymphomas, suggesting that there is an increased risk of lymphoma in children and adolescents with systemic inflammatory diseases treated with these agents compared with the general population. It remains unclear, however, what proportion of this increased risk can be attributed to the use of cytokine inhibitors, the underlying disease, or the effects of other immunosuppressive medications, which were used by 88% of patients in the analysis. Valid data on the background risk of lymphoma in children and adolescents with systemic inflammatory diseases are urgently needed.

Send Us a Letter!

Contact us at:

David Pisetsky, MD, PhD, physician editor

E-mail: [email protected]

Dawn Antoline, editor,

E-mail: [email protected]

Phone: (201) 748-7757

The Rheumatologist welcomes letters to the editor. Letters should be 500 words or less, and may be edited for length and style. Include your name, title, and organization, as well as a daytime phone number.

Conclusion

The data from three large biologics registers give reassuring messages regarding the overall risk of incident cancers in patients treated with TNF blocking agents. Concerning the clinically important question of whether we can treat patients with prior malignancies with these agents, an explanation for the discrepant results between the British and the German registers could be that in the German register, the time between onset of the first tumor and start of treatment with a TNF inhibitor was considerably shorter than in the BSRBR (mean, 7.4 years compared with 11.5 years). Further, there was a difference between the registers in the comparator groups—a mean of 7.4 years since the last tumor at start of a conventional DMARD in the German register and 8.5 years in the British register. This means that more patients in both groups in the German register and more patients in the control cohort in the British register were treated within a time window where we have to expect an increased risk of recurrence. This suggestion is supported by the fact that in the German register, the recurrent malignancies in the TNF groups were all true recurrences of the same tumor type and site, whereas in the British register, new tumor types mainly occurred, and those types were unrelated to the first tumor. With their strategy of waiting longer before starting treatment with TNF inhibitors, the British colleagues were more on the safe side, which may explain their even lower risk in the TNF inhibitor group. However, patients with very active disease may be willing to accept a potentially and insignificantly increased risk of recurrence for the sake of adequate treatment of their RA. Therefore, the final responsibility remains with the treating physician. Data from other countries, possibly reflecting different practice styles, may be able to elucidate this further in the near future.

Dr. Strangfeld is group leader of the pharmacoepidemiology group and Dr. Zink is head of the epidemiology department at the German Rheumatism Research Center in Berlin.

References

- Carswell EA, Old LJ, Kassel RL, et al. An endotoxin-induced serum factor that causes necrosis of tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:3666-3670.

- Coley WB. The treatment of malignant tumors by repeated inoculations of erysipelas. With a report of ten original cases. 1893. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;262: 3-11.

- Bongartz T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, et al. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: Systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006; 295:2275-2285.

- Bongartz T, Warren FC, Mines D, et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of malignancies. A systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008; 68:1177-1183.

- Dixon W, Silman A. Is there an association between anti-TNF monoclonal antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and risk of malignancy and serious infection? Commentary on the meta-analysis by Bongartz et al. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006; 8:111.

- Pincus T, Sokka T. Should contemporary rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials be more like standard patient care and vice versa? Ann Rheum Dis. 2004; 63(Suppl 2):ii32-ii39.

- Zink A, Strangfeld A, Schneider M, et al. Effectiveness of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis in an observational cohort study: Comparison of patients according to their eligibility for major randomized clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2006; 54:3399-3407.

- Askling J, van Vollenhoven RF, Granath F, et al. Cancer risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapies: Does the risk change with the time since start of treatment? Arthritis Rheum. 2009; 60:3180-3189.

- Strangfeld A, Hierse F, Rau R, et al. Risk of incident or recurrent malignancies among patients with rheumatoid arthritis exposed to biologic therapy in the German biologics register RABBIT. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010; 12: R5.

- Wolfe F, Michaud K. Biologic treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of malignancy: Analyses from a large US observational study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007; 56:2886-2895.

- Dixon WG, Watson KD, Lunt M, et al. Influence of anti-TNF therapy upon cancer incidence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have had a prior malignancy: Results from the BSR biologics register. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:755-763.

- Mercer LK, Galloway LB, Lunt M, et al. The influence of anti-TNF therapy upon incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA): Results From the BSR Biologics Register (BSRBR). Arthritis Rheum. 2009; 60 (10 Suppl):S772.

- 13. U.S.Food and Drug Administration. Information for healthcare professionals: Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers (marketed as Remicade, Enbrel, Humira, Cimzia, and Simponi). www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/ucm174474.htm. Published August 4, 2009. Accessed September 15, 2010.