WASHINGTON, D.C.—When she was a little girl, Dwinita Mosby Tyler, PhD, told her parents she wanted to be a ballerina.

Dr. Mosby Tyler

It wasn’t something they expected their 5-year-old, who is Black, to say, recalled Dr. Mosby Tyler, the founder of The Equity Project and a prominent speaker and trainer on diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), in her keynote address, The Transformative Power of Allyship in Rheumatology, on Nov. 15 at ACR Convergence 2024.

She said her mother took her to a ballet school, where they were told, “We don’t accept Negroes here.” Without a word, her mother took her to another ballet school, and another. All five they visited that day said the same thing.

“Why don’t they want me?” the young girl asked.

“Sweetheart, they don’t know how excellent you are yet,” said her mother.

The next day, a white lady in a leotard, tights and a tutu came to her segregated school. “My name is Miss Ann, and I’m going to be your ballet teacher,” she said.

Dr. Tyler said this was probably her introduction to the notion of equity.

Change Is Personal

“Equity can sometimes show up in unsuspecting packages,” she said. “Don’t let anybody convince you that it can’t be you.”

In her talk, Dr. Mosby Tyler drilled down on what diversity, equity and inclusion really mean and offered guidance and motivation on how to do your part. She challenged the common perceptions that some communities have little interest in DEI and the idea—and frequent pitfall—that change must come in a dramatic, sweeping fashion.

The ballet teacher visiting her school showed that “equity work takes bravery.” Miss Ann wasn’t even supposed to be in that neighborhood, let alone challenging an entire system. “She knew that little girls that looked like me couldn’t go to the ballet schools, so she brought the ballet school to us,” she said. And it showed that DEI must come from the heart.

“Equity work, as I have seen it, takes love and caring,” Dr. Mosby Tyler said. “And if you don’t have that in you, you’re not going to do it.”

It also comes in small steps that might not even be noticeable at the time, she said, telling audience members they may be engaging in “Miss Ann work” unwittingly.

“You probably don’t even know it yet,” she said. “But when you do know it, what you’re going to find out is that there is a moment, something that you did or said, that actually changed the trajectory of somebody’s entire life.”

Change can be made in “bite-sized pieces,” said Dr. Mosby Tyler. “Do what you can. Not everything has to be big, because this is a multiplier effect. Because for everything you do, there’s a million other people across the globe doing something, too.”

Active Allyship

Allyship—the act of engagement and support that is behind diversity, equity and inclusion work—should not be thought of as just a catch phrase, Dr. Mosby Tyler said.

“We often don’t use it as a verb; ‘to ally’ is an action,” she said. Dr. Mosby Tyler says she has seen a lot of passivity—a lot of “I stand for this, and I care for that.”

“What we’re after here is something called active allyship,” she said. “It’s where you witness something that might be an injustice or you might see a disparity, and you don’t just talk about it, you research it; you do something about it.”

She said much in the public discourse lately has been intended to discredit DEI.

“I don’t have to tell you, there’s a lot of rhetoric right now about ‘DEI—go away; go to sleep,’” she said. “And I want you to know, it is not going away. There are communities that are actively in this work because it betters their communities, and there are some unlikely communities that are in this work.”

The idea that mostly white, rural communities have no interest in DEI is inaccurate, says Dr. Mosby Tyler, something she knows from her own work.

“I do a lot of work in those particular communities. I knew that wasn’t the truth and that it was rhetoric and that people didn’t understand these communities that they were stereotyping,” she said.

The loss of the capacity for people to communicate, “to appeal to one another, to share stories with one another,” has to do with mental models, she said.

One person might be in a mental model of passive unawareness. For example, according to Dr. Mosby Tyler, someone not long ago told her they “just didn’t realize racism was as bad as it was”—and they were being honest.

Others may be in a model of passive awareness—knowing DEI issues are important but thinking they themselves have no role in them. Others are aware and also act. Some are aware and overly active, “without giving grace to someone not as far along as [they] are,” which can be counterproductive, giving rise to such phenomena as cancel culture.

Knowing the mental posture of another person can help with connection, she said.

It’s also important to understand the bases of social power, which include not only power based on position or title or the ability to punish, but also the power of experience and knowledge, and the power of mutual respect.

Understanding the bases of social power “helps people who don’t think they have any power—sometimes your patients, even—understand that they do have power.”

Do Something

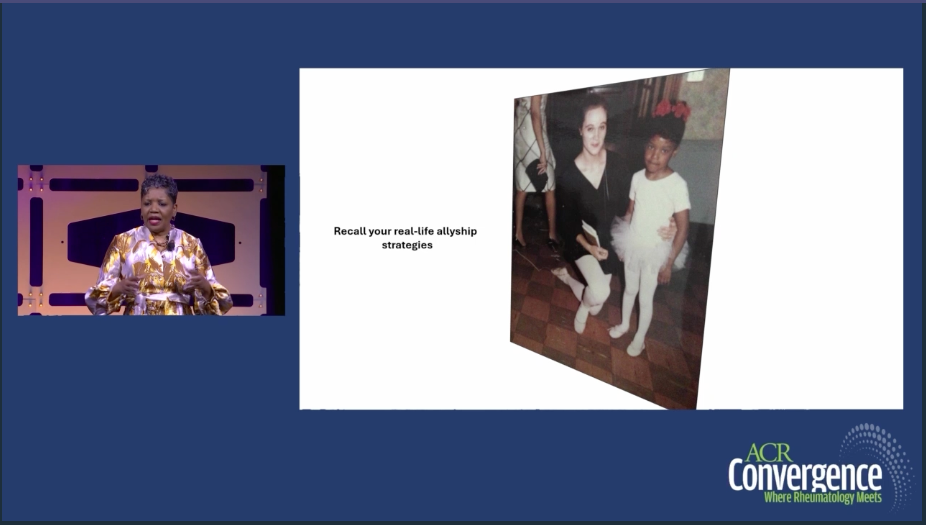

This screenshot from ACR Convergence 2024’s keynote address shows Dwinita Mosby Tyler, PhD, now and when she was a child, with Miss Ann, the ballet teacher who showed up for her.

Dr. Mosby Tyler underscored several keys to allyship and making DEI a reality. One is to examine the pushback impulse when data show that your organization has room for improvement.

“The hardest thing in this work, I think, is when you have to reveal something to the organization that they weren’t ready to hear,” she said. “There’s pushback because it just can’t be true.” These data should be seen as a remedy, she said, rather than a problem.

Also, she said, beware of delegating and relegating—getting others to do the work because you think you’re not the one equipped to do it.

Be aware, she added, that diversity means the totality of everyone. “We get stuck when we start making the word ‘diversity’ a synonym for race or a synonym for people of color,” she said. “And so, when you hear the word, and you’re not a person of color, you then don’t see yourself in the definition.”

Another hurdle is the increasingly prevalent decline bias, she said, a tendency to reference the past as the right way or best way to do something.

“People may be afraid to make changes that they have no evidence around. They don’t have the research, the evidence, and they don’t know if they want to change whole systems for equity if they don’t know how that’s going to work out—especially for them,” she said.

“I believe in a race neutral, gender neutral way that you are representing Miss Ann work each and every day. … Don’t let DEI complicate you. What you’re doing really does make a difference.”

Thomas Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

Thomas Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

Editor’s note: The session will be available on-demand to all registered ACR Convergence 2024 participants after the meeting through Oct. 10, 2025, by logging into the meeting website (https://acr24.eventscribe.net/index.asp).