Acknowledging a patient’s pain level and aiming to treat it can help geriatric patients have a better quality of life—some have peers who are active even over age 100, Dr. Makris says.

Although additional testing is sometimes required in elderly patients to rule out items on the differential diagnosis, think carefully before making that order, Dr. Makris recommended. “My question is always, ‘What will I do with this lab or imaging study?’ or ‘How will it help manage my patient?’ ” she says. “I find that many older patients come to me already with MRIs and we could have managed the conditions conservatively without any imaging.”

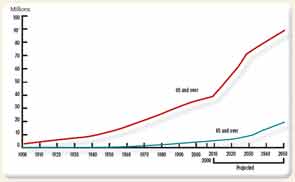

Note: Data for 2010–2050 are projections of the population. Reference population: These data refer to the resident population. Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Decimal Census, Population Estimates and Projections.

Balanced Treatment

Any treatment in the geriatric population should receive additional consideration to avoid causing further bodily harm. “In this population, where these individuals may be more frail, perhaps more socially isolated, with more multimorbidity and polypharmacy, we have to be especially careful and cognizant of the potential benefits and harms of our treatment,” Dr. Makris says.

One challenge when treating elderly patients is to help them feel better without causing an imbalance elsewhere in the body, Dr. Nakasato says. “A movement on the right side could cause an imbalance on the left side, and you get into a vicious cycle. The same can be said about medications. You might prescribe a medication that has a side effect. You give another medication for the side effect, and that causes another side effect. Breaking that cycle is difficult,” he says.

Medication management is always an issue, including the avoidance of medications that are not recommended for the elderly. “Medication prescribing can be limited by renal function or hepatic function or drug–drug interactions,” Dr. Makris says. She has used the American Geriatrics Society’s updated “Beer’s Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults” (see sidebar, p. 50) to help make medication decisions.

Some common medications to use with caution in the geriatric rheumatic population include:

- Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for OA. Guidelines for treatment published this year by the ACR (see sidebar, p. 50) indicate that systemic NSAIDs should usually be avoided in patients over age 75 to steer clear of gastrointestinal and renal function problems, Dr. Altman says. Instead, topical NSAIDs are a safer choice as they will enter the blood stream at a much lower level.

- Some types of immunizations. A patient taking a high dose of methotrexate may not be a good candidate for the herpes zoster immunization, Dr. Yung says.

- Hydroxychloroquine in RA patients. This medication can cause ocular risks in older patients, making annual eye exams especially important, Dr. Yung says.

- Analgesics such as narcotics, which can affect a patient’s balance. This could put these patients at a greater risk for falls, Dr. Altman says.

In addition to medication management, rheumatologists should consider the psychological benefits of encouraging physical and social activity, Dr. Makris says.