Resources for Geriatric Rheumatology

- ACR 2012 Recommendations for the Use of Nonpharmacologic and Pharmacologic Therapies in Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip and Knee: www.rheumatology.org/practice/clinical/

guidelines/PDFs/

ACR_OA_Guidelines_FINAL.pdf - American Geriatrics Society: www.americangeriatrics.org

- Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults: www.americangeriatrics.org/files/documents/

beers/2012BeersCriteria_JAGS.pdf - Health Literacy Consulting: Helen Osborne’s website featuring various articles and podcasts about better patient communication and education: http://healthliteracy.com and www.healthliteracyoutloud.com

- Herpes Zoster (Shingles) Vaccine Guidelines for Immunosuppressed Patients: www.rheumatology.org/publications/hotline/

2008_08_01_shingles.asp - Number of Older Americans: Contains a number of facts and figures on the elderly population growth in the United States: www.agingstats.gov/Main_Site/Data/

2010_Documents/Population.aspx

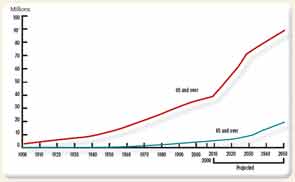

With the first crop of baby boomers turning 65 last year—part of the so-called silver tsunami that will cause the elderly population to double by 2030—there’s no question that rheumatologists are going to be treating older patients more frequently.

By 2050, the U.S. population over the age of 85 is expected to reach 19 million, compared with only 5.7 million in 2008, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Rheumatology patients in their late 70s, 80s, 90s, and 100s have some special considerations compared to the younger population.

“Older patients tend to have more comorbidities and resultant polypharmacy, making management issues for rheumatologic conditions more challenging,” says Una Makris, MD, assistant professor in the department of internal medicine in the division of rheumatic diseases at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

This means you’ll often find nonrheumatic comorbidities—for example, cardiovascular disease and diabetes—in addition to multiple rheumatological conditions, says Yuri Nakasato, MD, a rheumatologist at Sanford Health Systems and the University of North Dakota in Fargo. For example, a common scenario might be a patient with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), severe osteoarthritis (OA), and gout.

With individuals living longer, clinicians are now also observing the aging of rheumatic diseases, says Dr. Nakasato. This can include more sites of disease—for example, OA in the knees, hands, hips, and spine, Dr. Makris says.

“In the past, there was increased mortality. With that now decreasing, we’re seeing patients getting older,” Dr. Nakasato says. This adds another layer to the complexity of treatment.

At the same time, clinicians are treating patients for conditions that are occurring for the first time in their older age, such as elderly onset RA, says Raymond Yung, MB, ChB, chief of the division of geriatric and palliative medicine in the department of internal medicine and codirector of the geriatrics center at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Drs. Nakasato and Yung recently coedited a textbook called Geriatric Rheumatology (Springer, 2011).

Although geriatric patients can be among the most challenging to treat, there is a dearth of research-backed data on which to base diagnosis and treatment decisions, Dr. Makris says.

“Usually, older persons who have certain comorbidities and are ‘higher risk’ are excluded from clinical trials,” Dr. Makris says. “Therefore, our ability to make evidence-based decisions for these patients can be limited.”

Diagnostic Challenges

Diagnosing rheumatic disease in the geriatric population requires a keen ability to distinguish between actual disease and side effects from a medication, says Dr. Nakasato. This can be addressed, at least in part, with a thorough medication history, reminding patients to disclose over-the-counter supplementation as well as prescription drugs that they take, Dr. Yung says.

Discussing with patients the goal of treatment is also crucial, says Dr. Makris. “We should make an effort to talk to each of our older patients about what means most to them at this stage in their life—what are their priorities as far as outcomes we should be aiming for together,” she says.

For instance, the goal of treating back pain in a younger patient might be so they can return to work quickly. In a geriatric patient, their goal may be grocery shopping independently, gardening, or cooking, explains Dr. Makris.

At the same time, rheumatologists should not assume anything about what the patient can or cannot do. To truly assess function, ask repeated questions of both the patient and any caregivers who are present during the appointment, says Barbara Resnick, RN, PhD, Sonya Ziporkin Gershowitz Chair in Gerontology at the University of Maryland School of Nursing in Baltimore and chair of the board of directors for the American Geriatric Society.

“You sometimes have to ask the same question five different ways,” she says. “You might ask the patient if they are able to get their groceries on their own and they say it’s no problem. Yet their caregiver will tell you the patient hasn’t gone alone for six years.”

In addition to questioning, a thorough physical exam is also crucial, as older patients sometimes downplay their symptoms, says Roy D. Altman, MD, professor emeritus at UCLA Rheumatology in Los Angeles. “They may not understand their symptoms, or they don’t want to worry their families. There is also a lot of denial,” he says.

Older patients sometimes downplay pain or do not even report it to their physicians because they’ve been told, “it is just a normal part of aging,” says Dr. Makris. It is important for healthcare providers to be aware of their own biases. “When we get that pain scale rating, we should be doing a pain assessment to find out more about their pain and how it interferes [with] or affects their daily life. By acknowledging that our patients have pain that interferes with daily activities, we have the potential to really help our older patients,” she says.

Acknowledging a patient’s pain level and aiming to treat it can help geriatric patients have a better quality of life—some have peers who are active even over age 100, Dr. Makris says.

Although additional testing is sometimes required in elderly patients to rule out items on the differential diagnosis, think carefully before making that order, Dr. Makris recommended. “My question is always, ‘What will I do with this lab or imaging study?’ or ‘How will it help manage my patient?’ ” she says. “I find that many older patients come to me already with MRIs and we could have managed the conditions conservatively without any imaging.”

Note: Data for 2010–2050 are projections of the population. Reference population: These data refer to the resident population. Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Decimal Census, Population Estimates and Projections.

Balanced Treatment

Any treatment in the geriatric population should receive additional consideration to avoid causing further bodily harm. “In this population, where these individuals may be more frail, perhaps more socially isolated, with more multimorbidity and polypharmacy, we have to be especially careful and cognizant of the potential benefits and harms of our treatment,” Dr. Makris says.

One challenge when treating elderly patients is to help them feel better without causing an imbalance elsewhere in the body, Dr. Nakasato says. “A movement on the right side could cause an imbalance on the left side, and you get into a vicious cycle. The same can be said about medications. You might prescribe a medication that has a side effect. You give another medication for the side effect, and that causes another side effect. Breaking that cycle is difficult,” he says.

Medication management is always an issue, including the avoidance of medications that are not recommended for the elderly. “Medication prescribing can be limited by renal function or hepatic function or drug–drug interactions,” Dr. Makris says. She has used the American Geriatrics Society’s updated “Beer’s Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults” (see sidebar, p. 50) to help make medication decisions.

Some common medications to use with caution in the geriatric rheumatic population include:

- Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for OA. Guidelines for treatment published this year by the ACR (see sidebar, p. 50) indicate that systemic NSAIDs should usually be avoided in patients over age 75 to steer clear of gastrointestinal and renal function problems, Dr. Altman says. Instead, topical NSAIDs are a safer choice as they will enter the blood stream at a much lower level.

- Some types of immunizations. A patient taking a high dose of methotrexate may not be a good candidate for the herpes zoster immunization, Dr. Yung says.

- Hydroxychloroquine in RA patients. This medication can cause ocular risks in older patients, making annual eye exams especially important, Dr. Yung says.

- Analgesics such as narcotics, which can affect a patient’s balance. This could put these patients at a greater risk for falls, Dr. Altman says.

In addition to medication management, rheumatologists should consider the psychological benefits of encouraging physical and social activity, Dr. Makris says.

Elderly patients with OA may think physical activity is counterintuitive when they are in pain, but activity will help avoid weight gain, help prevent falls, and improve the OA symptoms, Dr. Altman says.

Rheumatologists, as well as other clinicians and caregivers, should work with geriatric patients to reduce their risk of fractures due to falls, Dr. Altman says. Remind caregivers to check the living environment for poor lighting or furniture hazards, such as rugs that can be tripped over.

Effective Patient Communication

Although effective patient communication is crucial with any patient population, it is especially important with older patients, who may also have vision, hearing, and cognition problems, says Helen Osborne, MEd, OTR/L, founder and president of Health Literacy Consulting in Natick, Mass. Osborne is author of the book, Health Literacy from A to Z (Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2nd edition, 2011).

Additionally, declining literacy skills, pain levels, independence issues, language barriers, culture, and emotion can all play roles in an elderly patient truly comprehending how they should manage their rheumatic disease. “It’s not just about understanding a brochure,” she says. “The patient has to learn, act on, and internalize information.”

Rheumatologists should make it a team effort to educate geriatric patients—or for that matter, any patients—about their disease, Resnick says. “The rheumatologist didn’t go to medical school to repeat patient education numerous times,” she says. “It takes a team effort.” Designate other staff members to help reinforce instructions and reiterate the important health promotion and disease modifying information that is critical to managing rheumatologic disease, Resnick says.

At the same time, during a visit with a patient, the clinician can try to match the patient’s language to make communication more effective, Osborne explains. For example, if the patient is using the phrase “water on the knee” to refer to knee effusion, you may want to match the patient’s terminology instead of using technical terms.

When describing conditions or providing instructions on how to take medication or how to perform certain exercises related to the patient’s rheumatic condition, “communicate that message consistently along the continuum of care,” Osborne advises. For some patients, this will include family members, home health staff, physical therapists, and other health professionals.

Osborne also recommends providing patient education in a variety of methods. In addition to brochures, consider visuals, audio and video, or manipulatives such as a model skeleton. “There’s no one-size-fits-all when it comes to patient education,” Osborne says.

When talking with elderly patients who may have other caregivers present, make sure to address the patient and caregivers equally, Resnick advises.

If you are creating written materials geared toward elderly patients, use a larger, darker font with few visual distractions, Resnick recommends.

Finally, when possible, take a little more time to answer an elderly patient’s questions. “I recently spent extra time with an 88-year-old patient,” Dr. Altman says. “Unfortunately, I don’t get paid for that, but he appreciated the time. He said, ‘You haven’t stuck a needle in me, but somehow I feel better.’ ”

Vanessa Caceres is a freelance medical writer in Bradenton, Florida.