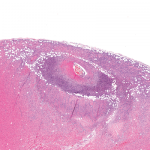

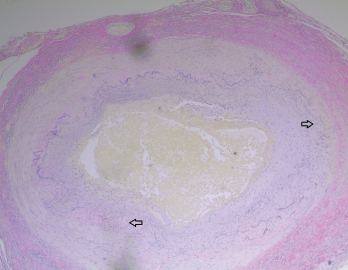

Figure 1. The biopsy of the right temporal artery with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was unremarkable.

Sarah2 / shutterstock.com

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a granulomatous vasculitis of large- and medium-sized arteries, usually affecting the cranial branches of the aortic arch. It is the most common vasculitis, with the highest risk factor being age. Accurate diagnosis and prompt initiation of therapy are of great importance to prevent serious complications, with the most feared being permanent vision loss.

The diagnosis is suspected clinically based on characteristic symptoms and laboratory findings, and confirmed histologically by temporal artery biopsy.

A classical presentation is easy to recognize when a patient older than 50 presents with a new-onset headache along with other characteristic findings, such as jaw claudication, symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) and elevated inflammatory markers. In clinical practice, however, GCA often presents diagnostic and management challenges.

These challenges arise from different factors, including:

- An atypical presentation (e.g., no headaches or atypical headaches, normal inflammatory markers or rare presenting symptoms, such as tongue or limb claudication, chronic cough, vertigo or oculomotor nerve palsy);

- A negative temporal artery biopsy despite the high probability of the disease based on clinical presentation. In this case, the clinician has to make the difficult decision to continue high-dose steroid therapy, which comes with the potential of serious adverse effects, or to stop therapy and risk serious complications, such as permanent vision loss;

- Temporal arteritis due to another form of systemic vasculitis, such as anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis or polyarteritis nodosa (PAN); or

- Intolerance to high-dose steroid therapy.

We present a case that highlights some of these challenges and provide some clinical pearls that can help in the diagnosis and management of GCA.

Case Presentation

Our patient is a 78-year-old woman with a past medical history of hypertension and osteoporosis. She initially presented to the emergency department with new-onset neck pain and headache that started after a long bus ride one week earlier.

The pain started as a right-sided posterior neck pain, which radiated to the right occipital scalp and then anteriorly toward the right frontal area. She described the pain as intermittent, sharp, shooting and severe, at times.

She had no constitutional symptoms, jaw claudication or proximal myalgias. Her neurological examination was normal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was obtained because of her acute-onset, severe headache, but was unremarkable. MRI of the cervical spine showed age-related degenerative changes.

Her laboratory evaluation was significant for a markedly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 73 mm/hr (reference range [RR]: 0–15 mm/hr) and C-reactive protein (CRP) of 87 mg/L (RR: <5–10 mg/L).

She underwent a unilateral right temporal artery biopsy (see Figures 1&2, above and opposite) and was started on 60 mg of prednisone daily for suspected GCA. Her headaches mildly improved, but her temporal artery biopsy result was did not demonstrate evidence of vasculitis. Given her negative biopsy results, GCA was considered unlikely, and the prednisone was tapered off over two weeks.

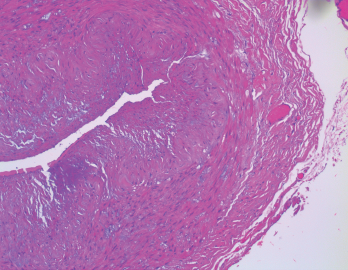

Figure 2. In the biopsy of the right temporal artery with elastin staining, the internal elastic lamina is preserved despite the appearance of artifactual interruptions in the internal elastic layer caused by specimen processing.

She was started on gabapentin for presumptive right-sided occipital neuralgia. Her headaches persisted but were less severe.

One day after she discontinued prednisone, she awoke with diplopia and right eye ptosis, prompting her to return to the emergency department. This is when we met the patient.

Her exam revealed a pupil-involving, partial, right third cranial nerve palsy. She had a partial ptosis, medial rectus palsy and non-reactive pupil. Her left superficial temporal artery was indurated. Her laboratory tests were again significant for a marked elevation in her inflammatory markers (ESR: 86 mm/hr; CRP:186 mg/L).

The differential diagnosis of a severe headache and third nerve palsy includes aneurysmal third nerve involvement, microvascular ischemic cranial neuropathy, inflammatory meningitis as in neurosarcoidosis, carcinomatous meningitis and GCA.

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the head and neck was performed, and MRI of the brain and orbits was also obtained. The head CTA showed no evidence of aneurysm. The neck CTA showed an irregularity of the external carotid arteries on both sides, raising concern for vasculopathy.

The patient underwent a lumbar puncture, and the analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was unrevealing. Her third nerve palsy, new headache, elevated ESR/CRP, and imaging findings made us most suspicious for GCA.

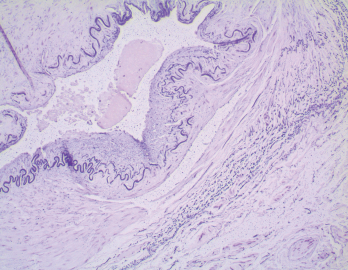

Figure 3. The biopsy of the left temporal artery with H&E staining shows multinucleated giant cells.

She was started on 1,000 mg of intravenous methylprednisolone daily. A left temporal artery biopsy was performed the next day (see Figures 3&4, opposite). Her symptoms began to improve within hours of starting the intravenous steroids, and all of her symptoms resolved within 48 hours.

The left temporal artery biopsy showed full-thickness inflammation of the vessel involving the intima, media and adventitia. The inflammatory cells included eosinophils, lymphocytes, scattered neutrophils and many multinucleated giant cells. The pathology was consistent with a diagnosis of GCA.

After receiving intravenous methylprednisolone for three days, she was started on 1 mg/kg of oral methylprednisolone. The dose was tapered gradually, according to GCA treatment protocols.

She had side effects of severe insomnia, facial swelling and moderate weight gain after starting steroid therapy. She refused to start tocilizumab initially because she was concerned about the potential side effects.

Her right-sided headaches recurred on two occasions when she was tapered to 12 mg per day of methylprednisolone and improved quickly when the dose was raised back to 16–20 mg per day.

At this point, our patient agreed to start tocilizumab therapy. It was administered as monthly intravenous infusions at a dose of 8 mg/kg. After she started tocilizumab, the methylprednisolone dose was able to be decreased rather rapidly.

Six months after her diagnosis, she was down to 4 mg per day of methylprednisolone. She remained asymptomatic with normal inflammatory markers.

Discussion

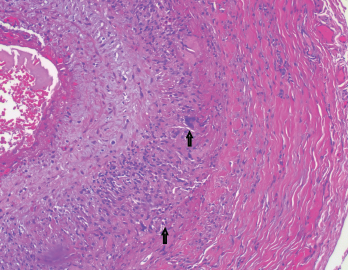

Figure 4. The biopsy of the left temporal artery with elastin staining shows disruption of the internal elastic lamina.

Giant cell arteritis is the most common form of systemic vasculitis in North America and can lead to serious complications if not diagnosed promptly and treated appropriately. The classic presentation is of new-onset temporal headaches (usually unilateral) along with jaw claudication and/or proximal myalgias and arthralgias in a patient over the age of 50.

The clinical suspicion is usually confirmed by markedly elevated inflammatory markers and a rapid response to high-dose steroids. Temporal artery biopsy is the gold standard to confirm the diagnosis, but clinical suspicion of GCA is enough to commence steroid treatment to avoid the dreaded complication of vision loss.

Occasionally, atypical presentations present challenges in diagnosis and management. Our case highlights some of these challenges, and we offer some clinical pearls. Consider:

The type of headache

The main feature is that the headache is new.

Many clinicians associate GCA with severe temporal headaches associated with scalp tenderness. In practice, the headache location is variable and can be frontal, temporal, parietal, occipital or generalized.1 The headache phenotype is also nonspecific. It can have features of a tension or migraine headache. On occasion, GCA can present without headaches, making the diagnosis even more difficult.

Uncommon presenting symptoms

Consider GCA in a patient who presents with oculomotor palsy.2-4

In this case, the patient presented to us with headache and diplopia due to a pupil-involving, partial third nerve palsy. Oculomotor nerve palsies have been uncommonly described in patients with GCA, and pupillary involvement is even rarer. Pupillary involvement usually signifies a compressive lesion of the third nerve because the pupillary fibers lie on the periphery of the nerve. Nerve ischemia related to GCA is thought to typically affect the center of the nerve more than the periphery.4

Examples of other uncommon presenting symptoms include posterior circulation strokes, upper respiratory tract symptoms, tongue pain and tongue necrosis, mesenteric ischemia and pericarditis.5,6

Temporal artery biopsy

Perform unilateral vs. bilateral temporal artery biopsies when GCA is suspected.

The new guideline for the management of GCA, from the ACR in concert with the Vasculitis Foundation, recommends initially pursuing a unilateral temporal artery biopsy over bilateral biopsies. The recommendation is to proceed with a contralateral biopsy if the initial unilateral biopsy is negative and additional evidence for GCA diagnosis is sought.7

A recent meta-analysis of 32 studies published during 1993–2017 estimated the sensitivity of the temporal artery biopsy at 77%. The sensitivity was even lower (68%) for studies published after 2012.8 We are concerned that in clinical practice the treating physician will often have to face the difficult decision of whether to perform the contralateral biopsy if the unilateral biopsy result is unrevealing.

In our patient, although the biopsy of the symptomatic side was normal, the biopsy of the asymptomatic side demonstrated the pathology of GCA. Although the superficial temporal artery on the symptomatic side was likely affected, GCA involvement of the arteries is known to be segmental rather than contiguous and biopsy of a portion of an artery can result in sampling error. The same vascular surgeon performed both biopsies, and the same technique was used.

Similar discordant findings in bilateral temporal artery biopsy results have been reported in previous studies.9,10 For this reason, it is still not uncommon in practice for physicians to request bilateral biopsies up front.

It is crucial to remember that an unrevealing temporal artery biopsy does not rule out GCA. If compelling evidence supports a diagnosis of GCA, then treatment should be continued.

Imaging

Vascular imaging can be useful to aid in the diagnosis of GCA.11

Many studies have shown imaging can be helpful in diagnosing GCA with relatively high sensitivity and specificity, but imaging is still not widely utilized in the evaluation and diagnosis of GCA. Color Doppler ultrasound of the temporal arteries is promising and is considered the first-line imaging modality for GCA diagnosis, but the operator-dependent nature limits its use at this point outside large academic centers.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan and MR angiography with contrast can demonstrate signs of vasculitis in the temporal arteries and aid in the diagnosis of GCA with high sensitivity and specificity, but factors including cost, availability, the need for contrast (in the case of MR) and radiation exposure (in the case of PET scan) limit their use.

In our patient, CTA of head and neck showed irregularities of the external carotid arteries that increased our suspicion for GCA.

Always consider performing bilateral temporal artery biopsies when GCA is suspected.

High-dose, long-term steroids

Consider tocilizumab as a steroid-sparing agent.8

Although corticosteroids are an extremely effective treatment for GCA, their use is frequently limited by multiple short- and long-term adverse effects. Our patient developed severe insomnia and facial swelling early on that markedly affected her quality of life. Additionally, as is the case in many patients, our patient’s symptoms resurfaced in the midst of two attempts to wean her steroid dosage. After tocilizumab was started, we were able to taper the steroids without recurrence of symptoms.

Tocilizumab should be a first-line agent, along with steroids, to limit steroid exposure, and it could be especially helpful in certain patients with comorbid conditions, such as diabetes, osteoporosis or congestive heart failure.

Ashraf Raslan, MD, completed his rheumatology fellowship at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J., and is a practicing rheumatologist with Valley Medical Group, Ridgewood, N.J.

Ashraf Raslan, MD, completed his rheumatology fellowship at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J., and is a practicing rheumatologist with Valley Medical Group, Ridgewood, N.J.

Dorian Infantino, MD, has been a fellow of the American College of Pathologists since 2017 and is an anatomic and clinical pathologist with The Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, N.J.

Dorian Infantino, MD, has been a fellow of the American College of Pathologists since 2017 and is an anatomic and clinical pathologist with The Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, N.J.

Roman Zuckerman, DO, is a rheumatologist at The Valley Health System, Ridgewood, N.J., with an interest in vasculitides.

Roman Zuckerman, DO, is a rheumatologist at The Valley Health System, Ridgewood, N.J., with an interest in vasculitides.

Daniel Berlin, MD, is a neurologist with subspecialty training in electromyography. He currently sees patients in Ridgewood, N.J.

Daniel Berlin, MD, is a neurologist with subspecialty training in electromyography. He currently sees patients in Ridgewood, N.J.

References

- Tanganelli P. Secondary headaches in the elderly. Neurol Sci. 2010 Jun;31(Suppl 1):S73–S76.

- Walters B, Lazic D, Ahmed A, Yiin G. Lesson of the month 4: Giant cell arteritis with normal inflammatory markers and isolated oculomotor palsy. Clin Med (Lond). 2020 Mar;20(2):224–226.

- Thurtell MJ, Longmuir RA. Third nerve palsy as the initial manifestation of giant cell arteritis. J Neuroophthalmology. 2014 Sep;34(3):24–245.

- Davies GE, Shakir RA. Giant cell arteritis presenting as oculomotor nerve palsy with pupillary dilatation. Postgrad Med J. 1994 Apr;70(822):298–299.

- Imran TF, Helfgott S; Respiratory and otolaryngologic manifestation of giant cell arteritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015 Mar-Apr;33(2 Suppl 89):S164–S170.

- Sujobert P, Fardet L, Marie I, et al. Mesenteric ischemia in giant cell arteritis: 6 cases and a systemic review. J Rheumatol. 2007 Aug;34(8):1727–1732.

- Maz M, Chung SA, Abril A, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology/Vasculitis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Giant Cell Arteritis and Takayasu Arteritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021 Aug;73(8):1071–1078.

- Rubenstein E, Maldini M, Gonzalez-Chiappe S, et al. Sensitivity of temporal artery biopsy in the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020 May 1;59(5):1011–1020.

- Breuer G, Nesher G, Nesher R. Rate of discordant findings in bilateral temporal artery biopsy to diagnose giant cell arteritis. J Rheumatol. 2009 Apr;36(4):794–796.

- Durling B, Toren A, Patel V, et al. Incidence of discordant temporal artery biopsy in the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2014 Apr;49(2):157–161.

- Serling-Boyd N, Stone JH. Recent advances in the diagnosis and management of giant cell arteritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2020 May;32(3):201–207.