NEW YORK (Reuters Health)—Patients with vitiligo commonly have other autoimmune diseases, according to a cross-sectional study.

“Vitiligo is a systemic disease with multiple comorbidities,” Dr. Iltefat Hamzavi from Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, Mich., told Reuters Health by email. “The number of patients with neurologic diseases and inflammatory disease was much higher than we anticipated.”

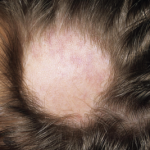

Vitiligo, with an estimated prevalence ranging from 0.5% to 1%, is characterized by selective loss of melanocytes and patchy depigmentation of the skin and mucous membranes. Autoimmunity is thought to play a role in its pathogenesis.

Based on a manual chart review involving nearly 1,100 patients with vitiligo, Dr. Hamzavi and colleagues found that 19.8% had at least one comorbid autoimmune disease, and 2.8% had more than one, they report in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, online Oct. 27.

The two most common comorbid autoimmune diseases were thyroid disease (12.3% of patients) and alopecia areata (3.8% of patients).

Other autoimmune diseases with significantly increased prevalence (compared with the general population) included discoid lupus, Guillain-Barre syndrome, linear morphea, myasthenia gravis, pernicious anemia, Sjogren syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Female patients with vitiligo had a higher prevalence of comorbid thyroid disease than did male patients with vitiligo (18.5% vs. 5.1%; p<0.001), but there were no other differences between the sexes.

Patients with at least one comorbid autoimmune disease tended to have more extensive vitiligo, compared with those who had no comorbid autoimmune disease.

“This builds on the theory pointing to an autoimmune pathogenesis for vitiligo,” Dr. Hamzavi says. “Most patients with vitiligo will not develop autoimmune disease, but a significant minority will develop hypothyroidism. Patients with vitiligo should be regularly screened yearly for thyroid disorders.”

“Also the rates of other autoimmune diseases like alopecia areata, inflammatory bowel disease, Guillain Barre, SLE (lupus), and others were observed at a much higher rate than one would expect,” Dr. Hamzavi says. “Patients should be asked if they have symptoms of these diseases when evaluated by their physicians.”

“We need better treatments for vitiligo which target the cause of the disease,” Dr. Hamzavi adds. “We hope that this work can be used by patients, physicians and researchers toward that end.”

“Prospective studies of vitiligo with a control group are needed to confirm the significance of our findings and may help uncover the sequence of development of these conditions,” the authors conclude.

Dr. Katia Boniface from Universite de Bordeaux in France, who was not involved in the new work, has studied the immune mechanisms of vitiligo. She told Reuters Health by email, “It is an interesting clinical study supporting previous findings demonstrating that an important proportion of vitiligo patients display at least one other comorbid autoimmune disease, in favor of the autoimmune theory to explain melanocyte disappearance in this disease.”