Myelofibrosis is a hematologic process characterized by bone marrow reticulin fibrosis and mainly associated with myelodysplastic disorders in which the level of fibrosis is variable. It can also present in the setting of an autoimmune disease, hence the term autoimmune myelofibrosis (AMF).

AMF is a rare condition that has been linked to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). For example, in one series of 27 patients with AMF, 18 had SLE.1 However, there are only two prior cases of AMF affecting Hispanic patients with SLE reported in the medical literature.2

Case report

Our patient is a 25-year-old Hispanic female with SLE characterized by myositis, nephrotic syndrome and cutaneous lesions. Laboratory abnormalities included a positive antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-Smith antibodies, double-stranded DNA antibodies, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, proteinuria, hypocomplementemia and elevated liver enzymes. The latter were thought to be consistent with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH).

In 2005, she was admitted with pancytopenia (total leukocyte count 3,000/mm3, differential: neutrophils 89%; lymphocytes 7%; monocytes 4%; hemoglobin 8.3 g/dL; hematocrit 24%; platelet count 10/mm3). She was initially treated with methylprednisolone at 1 mg/kg a day and mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg twice a day without improvement in her cell counts.

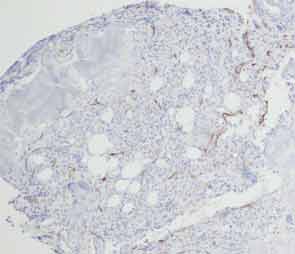

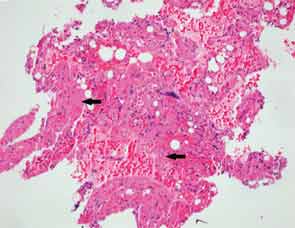

A bone marrow biopsy showed the presence of myelofibrosis with decreased hematopoietic cells on CD34 immunohistochemical stain and replacement of normal bone marrow with fibrotic tissue (see Figures 1, cover, and 2). The patient was pulsed with high-dose IV methylprednisolone and a five-day course of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Her cell counts improved with a leukocyte count of 7,500/mm3 (differential: neutrophils 81%; lymphocytes 8%; monocytes 11%); hemoglobin 8.6 g/dL; hematocrit 25%; and platelets 104,000/mm3.

An attempt was made to decrease her dose of corticosteroids by instituting a regimen of mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus. However, the patient developed new leukopenia episodes when the steroid dose was decreased. She was evaluated for a new episode of neutropenia, thought to be caused by her immunosuppressant medications because it improved after these drugs were stopped. She was later restarted on tacrolimus 2 mg BID, and azathioprine was added to treat the AIH (liver enzymes: AST 99; ALT 133; leukocyte count 4,000/mm3; hemoglobin 10.1 g/dL; hematocrit 29%; platelet count 136/mm3).

The patient moved to Mexico (2008–2012) and was managed only with prednisone 10 mg daily. When the patient was seen after a hiatus of four years, she was restarted on azathioprine 100 mg daily. This was increased to 150 mg when her liver enzymes increased following a decrease in her prednisone dose. Unfortunately, she developed pancreatitis that was attributed to the azathioprine, and it was discontinued. The prednisone dose was increased to 60 mg daily and slowly tapered to 15 mg per day. However, her liver enzymes rose again, and she was given a trial of mycophenolate mofetil 1 g BID. She presented with a new episode of pancytopenia, and this medication was discontinued.

In May 2013, the patient was admitted to the hospital due to fever. An infection workup was negative. The laboratory tests were consistent with Coombs-positive autoimmune hemolytic anemia. The serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 921 U/L: haptoglobin

Unfortunately, the patient was shortly readmitted with sepsis secondary to perineal cellulitis, pancytopenia and fevers. The decision was made to treat the patient with a course of IVIG 1 g/kg/infusion. Following the third dose, her cell counts started to improve (leukocyte count of 8,000/mm3; differential: neutrophils 87%; lymphocytes 7%; monocytes 2%; hemoglobin 10.4 g/dL; hematocrit 32%; platelet count 151/mm3). The patient was discharged home on a dose of prednisone 50 mg daily.

Discussion

AMF has been defined by the following criteria: Grade 3 or 4 reticulin fibrosis of the bone marrow, lymphocyte infiltration of the bone marrow, lack of osteosclerosis, absent or mild splenomegaly, presence of autoantibodies and the absence of a disorder known to be associated with myelofibrosis (e.g., lack of clustered or atypical megakaryocytes, myeloid or erythroid dysplasia, eosinophilia and basophilia).3 SLE seems to be the leading cause of AMF in the literature.1 It’s difficult to calculate the true incidence and prevalence of AMF. Mehta et al performed a database analysis and found that among the 1,753 patients diagnosed with a secondary myelofibrosis, 54 (3.1%) had SLE as their primary diagnosis.4 Wanitpongpun et al evaluated a cohort of 44 patients with SLE and cytopenias and found that 20 had bone marrow abnormalities, but only 5% had signs of myelofibrosis.5 The level of fibrosis can vary between patients. For example, Voulgarelis et al found mild to marginal signs of fibrosis (Bauermeister score 1+ and 2+) in 60% of patients (n=40) with cytopenias, while the remaining 40% presented with moderate to severe signs of fibrosis.6 The etiology for AMF is unknown. It’s believed that lymphocytes directly,7 or indirectly through immune complexes,8 stimulate megakaryocytes to secrete transforming growth factor β, vascular endothelial growth factor and fibroblast growth factor. These cytokines activate and stimulate fibroblasts to produce fibronectin, type IV collagen, chondroitin, dermatan and proteglycans. Glucocorticoids are the first-line treatment for AMF. A review of 17 patients with AMF and SLE by Kagenyama et al noted improvement in the 14 of 16 patients who received steroids.9 There is improvement in the appearance of the peripheral smear, and in the bone marrow, there may be a concomitant decrease or resolution of fibrosis.10 Due to lack of randomized controlled studies, the optimal dose of steroids is unknown.11,12 The use of IVIG 2 g/kg divided over five days has shown good results.13 Splenectomy has also been reported to improve cytopenias.14 Our patient repeatedly responded to IVIG and varying doses of steroids including methylprednisolone pulse (1 g IV for three days) and maintenance dose of prednisone 20 mg. To date, we have been unable to completely discontinue the drug.

Mell Gutarra-Arana, MD, and Tehniat Haider, MD, are rheumatology fellows at Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis.

Theodore Kieffer, MD, is an anatomic and clinical pathology resident at Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianopolis.

Steven Hugenberg, MD, is chief of the Division of Rheumatology at Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianopolis.

References

- Rizzi R, Pastore D, Liso A, et al. Autoimmune myelofibrosis: Report of three cases and review of the literature. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004 Mar;45(3):561–566.

- Paquette RL, Meshkinpour A, Rosen PJ. Autoimmune myelofibrosis. A steroid responsive cause of bone marrow fibrosis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994;73(3):145–152.

- Santos FP, Konoplev SN, Lu H, Verstovsek S. Primary autoimmune myelofibrosis in a 36-year-old patient presenting with isolated extreme anemia. Leuk Res. 2010 Jan;34(1):e35–e37.

- Mehta J, Wang H, Iqbal SU, Mesa R. Epidemiology of myeloproliferative neoplasms in the United States. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014 Mar;55(3):595–600.

- Wanitpongpun C, Teawtrakul N, Mahakkanukrauh A, et al. Bone marrow abnormalities in systemic lupus erythematosus with peripheral cytopenia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012 Nov–Dec;30(6):825–829.

- Voulgarelis M, Giannouli S, Tasidou A, et al. Bone marrow histological findings in systemic lupus erythematosus with hematologic abnormalities: A clinicopathological study. Am J Hematol. 2006 Aug;81(8):590–597.

- Bass RD, Pullarkat V, Feinstein DI, et al. Pathology of autoimmune myelofibrosis. A report of three cases and a review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001 Aug;116(2):211–216.

- Hasselbalch H, Nielsen H, Berild D, Kappelgaard E. Circulating immune complexes in myelofibrosis. Scand J Haematol. 1985 Feb;34(2):177–180.

- Kageyama Y. [A case of elderly-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) complicated with severe liver dysfunction and pancytopenia due to myelofibrosis.] (Article in Japanese.) Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 1999 Dec;36(12):881–886.

- Konstantopoulos K, Terpos E, Prinolakis H, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus presenting as myelofibrosis. Haematologia (Budap). 1998;29(2):153–156.

- Kaelin WG Jr, Spivak JL. Systemic lupus erythematosus and myelofibrosis. Am J Med. 1986 Nov;81(5):935–938.

- Kiss E, Gál I, Simkovics E, et al. Myelofibrosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000 Nov;39(5–6):661–665.

- Zandman-Goddard G, Levy Y, Shoenfeld Y. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy and systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2005 Dec;29(3):219–228.

- Harrison JS, Corcoran KE, Joshi D, et al. Peripheralmonocytes and CD4+ cells are potential sources for increased circulating levels of TGF-beta and substance P in autoimmune myelofibrosis. Am J Hematol. 2006 Jan;81(1):51–58.