On a highway traversed by cement trucks and Beetle-Bug auto-rickshaws we travel north from Bangalore, India, for a house call. It is 2007, and the city leaves us grudgingly. Between fields of loose chocolate soil and sprigs of beans poking skyward, the skeletons of homes and businesses rise; armies of workers lay brick from wooden scaffolds; hawkers sell car tires, shock absorbers, beds and tombstones.

On a highway traversed by cement trucks and Beetle-Bug auto-rickshaws we travel north from Bangalore, India, for a house call. It is 2007, and the city leaves us grudgingly. Between fields of loose chocolate soil and sprigs of beans poking skyward, the skeletons of homes and businesses rise; armies of workers lay brick from wooden scaffolds; hawkers sell car tires, shock absorbers, beds and tombstones.

Stanley Macaden, MD, an internist at Bangalore Baptist Hospital, inches our van forward in heavy traffic. In the back seat, two community health nurses chat quietly while Dr. Macaden reviews the details of our house call with me: “Thirty-one years old. Rheumatoid arthritis for 20 years. Non-ambulatory. It’s a difficult case. She has much pain and often cries throughout our visit. She’s cared for by her mother, who does a good job, but they are set in their ways. We’ll take a look.”

With each passing mile, the traffic thins and the rural nature of India declares itself. An egret stalks fish in a verdant pool of duckweed and water lilies. Hawks soar lazily overhead. Stands of palm trees shade thatch-roof homes. Wandering cattle, oblivious to traffic, stray into our lane and stop momentarily, chewing, flicking their tails. We turn off the paved road and bounce along a rolling dirt lane before pulling over at a low-set, tin-roofed hut facing a narrow alley. The dust settles as we gather our supplies. At the entry, cow dung has been dried into a hard, odorless welcome mat.

The Patient

Inside, I make out a rumpled sheet on a thin gray mat. It is rectangular, about three and a half feet long. Embers from the morning fire glow in the far corner of the hut. Light from the open entry sends a shaft of light to the edge of the sheet, and as my eyes adjust, I can make out a faint blue discoloration to the fabric. I lightly touch the smooth, velvety linen. The sheet rises and falls. Beneath my hand, there is a young woman.

Maria’s mother squats next to the hidden form and coos a greeting as she unwraps the edge of fabric where a tuft of hair protrudes. A woman’s head emerges. Her facial skin is like a newborn’s: plump and fat, unwrinkled, downy hair around the lip and chin like the fuzz on a peach. Mother’s and daughter’s eyes meet. Another day begins.

Dr. Macaden squats down for a closer look, and I sit awkwardly, shifting unwilling knees in search of a comfortable position. The two nurses speak softly to Maria and her mother in the region’s lilting Kannada tongue. “Our drive was pleasant. The fields look healthy. This is Dr. Macaden, whom you know. This is the American doctor. He is a specialist in arthritis and wants to help you.”

The mother considers this as she runs a comb through her daughter’s hair, humming softly. Then she reaches back into the shadows and hands a plastic bag to the nurses. One nurse empties the contents onto the mat, separates the pills into small piles, counts them and asks about effectiveness and side effects, while the other tallies the results in a notebook.

The older nurse asks, “Mother, do you give Maria this pill only once each week?” The mother nods solemnly. She explains that the mailman comes to the village once each week, and it is on this day she gives the special pill to Maria with a glass of water.

I recognize the methotrexate, diclofenac, cimetidine and a 10 mg tablet of prednisone and point to an unknown pill. Dr. Macaden whispers to me, “The pink pill is for depression.”

Then, “Mother, do you give Maria the pink pill? Does she cry less?”

“Yes, I give her the special pill. Can you make it stronger? She still cries, but not all day.”

“And how is her pain,” Dr. Macaden asks.

“The pain is very bad,” the mother says.

“Maria,” Dr. Macaden places his hand lightly on her forehead. “How is your pain? Does the medication help with pain?” In a faint, hoarse whisper, Maria answers, “No. The pain is always with me, even when I sleep. I dream about the pain.”

Dr. Macaden explains to me in English, “She is on morphine. It’s a low dose, but it’s not helping. She says the pain is no different. Perhaps you can take a look.”

My Examination

A nurse asks Maria if I can examine her hands. I move closer, and she groans as I cradle her hand in my palm. The fingers overlap and droop in partial flexion, drifting uselessly away from the thumb. She cannot extend her fingers or pinch between her thumb and index finger. It’s clear that she is unable to hold a glass or use a spoon. Her elbows are in a fully flexed state, the shoulders nearly immobile. Maria holds her arms crossed over her chest like a living sarcophagus. When I attempt to straighten her elbows or range her shoulders, there is an audible clunk, and she cries out and begins to sob.

We provide charity care at our hospital, but there are limits. For the cost of one year of Enbrel, we can provide immunizations to a thousand children.

Uncovering her lower legs, I understand why she cannot walk. The knees and hips are also contracted, her thighs nearly touching her abdomen, her knees flexed at 90º. If she were upright, she would appear in a perpetual squat. I rock her hip gently, and she cries out. There is roughly half a cup of fluid in each knee. Everywhere I lightly touch a joint, there is warmth and a hint of redness.

In such cases, something can always be done to help, to offer some measure of comfort, but I know my tools are limited. Hip, knee and shoulder replacement might restore her ability to walk and reduce pain, but finding an orthopedic surgeon willing to tackle the job—gratis, in an 80 lb. patient is a tall order. I make a mental note to ask Dr. Macaden on our way home if this is even a remote possibility.

“The methotrexate,” I ask, “what is the dose?”

“Fifteen mg weekly,” Dr. Macaden answers. “We wish we could increase the dose, but her liver enzymes are slightly elevated. We are giving her daily folic acid and will be drawing blood today.”

I quietly evaluate our options. According to Dr. Macaden, hydroxychloroquine was discontinued years before due to a lack of efficacy. In the face of elevated liver enzymes, leflunomide is contraindicated.

“Sulfasalazine?” I ask. “Has she had a trial of sulfasalazine?”

“To substitute for the methotrexate?”

“No, to add to it. It may be of some benefit,” I answer. Dr. Macaden jots down the dosage and silently nods. “And the prednisone, perhaps you can nudge that up as well,” I add.

Foremost in my mind is whether a trial of a biologic could be prescribed, but before I could ask, Dr. Macaden says, “Enbrel was suggested last year, but it’s not available for her. We provide charity care at our hospital, but there are limits. For the cost of one year of Enbrel, we can provide immunizations to a thousand children.” He was silent for a moment. “There are many Marias.”

I draw up four cortisone injections for Maria’s knees and shoulders, identifying them as the most symptomatic joints. Maria’s mother softly explains to her daughter that the needle will hurt, but the shots will help with pain. I have been told by my Indian co-workers that injections are held in high esteem by the local population. It is what separates traditional healers from physicians—and a sign that a doctor is doing all they can to improve their patient’s illness. I scrub the injection sites thoroughly, acutely aware that I am injecting the knees and shoulders of a woman who is non-ambulatory and spends her days underfoot in the loving care of her mother and siblings. The injections will help … for a few weeks, a month or two at most, but long-term, meaningful improvement will only come with a combination of joint replacement and the addition of a biologic.

It is a difficult truth, but at 31 years of age, Maria is slowly, inexorably dying.

Reflections

On the way back to the city, I reflect on Maria. Although it is 2007, I feel like I have been transported back to my first year in practice in 1985, to the many failures of treatment our patients suffered through. Older rheumatologists can still remember when we relied on gold, capable of placing a few patients in remission, but fraught with side effects and ineffective for the majority. Methotrexate was utilized, but often cautiously, and in relatively low doses.

At my weekly rheumatology conference at Maine Medical Center, Phil Thompson MD, 20 years my senior, recalled hospitalizing patients with rheumatoid arthritis with complications of the disease we rarely see today: vasculitis, pleuro-pericardial effusions, secondary amyloidosis and infections from high-dose corticosteroid treatment. Despite his best efforts, these patients frequently died.

I remember my grandfather, Rice Beavers, afflicted for the last seven years of his life by a combination of rheumatoid arthritis and Parkinson’s disease in rural West Virginia in the early 1970s. Once a vibrant blacksmith and farmer, year by year he was beaten down to a state of helplessness and dependency. A hired man lifted him from bed each day into his wheelchair, dressed him, bathed him and strapped a spoon to his hand so he could feed himself. Two years before he died, he was bedbound and no longer able to feed himself.

From time to time, I consult on old-time patients with rheumatoid arthritis in my practice in northeast Maine—patients whose disease has inexorably progressed without a trial of an aggressive disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug or biologic.

Just four months ago, I received a phone call about a family fleeing the war in their native Ukraine with their 5-year-old daughter, who had previously been diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. They arrived in Maine with nothing but the clothes they could carry. The girl was beginning to flare. I called Ed Fels, a pediatric rheumatologist, who cut through the red tape and promptly arranged for her to restart adalimumab. But what if they had landed in a refugee settlement? What if adalimumab were simply unavailable?

It is in these moments that I remember Maria, the burden of disease she carried and the loving care she received from her family and healthcare workers.

We should never take for granted the immense progress basic science, clinical trials and the availability of effective treatment has made in our patients’ lives. There were once many Marias, but there are far fewer today, and for that we should be thankful.

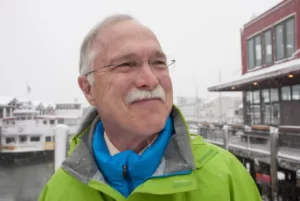

Dr. Radis

This essay was originally written in 2007, while Charles Radis, DO, was a visiting attending at Bangalore Baptist Hospital, India. Since then, Bangalore Baptist Hospital has grown considerably and now has a rheumatologist on staff. Dr. Radis continues to practice part time in Maine and is a clinical professor of medicine at the University of New England, College of Osteopathic Medicine. He can be reached at [email protected] or through his website at www.doctorchuckradis.com.