There are no symptoms pathognomonic for cartilage defects, and patients are frequently diagnosed with meniscal tears or patellofemoral syndrome initially.

Physical Findings

Similar to the patient’s presenting complaint, physical examination will not produce any findings specific for cartilage repair. Range of motion is usually preserved, although displaced osteochondral fragments can lead to intermittent locking. Large defects, especially in the patellofemoral compartment, can lead to reproducible catching or clicking with active and passive motion and patellar manipulation. Tenderness to palpation of the femoral condyles and joint spaces suggests the presence of synovitis. Given the importance of articular comorbidities, particular attention should be focused on the assessment of ligamentous stability, patellar maltracking, and alignment.

Diagnostic Imaging

Standard radiographs are utilized to screen for advanced osteoarthritic changes that would rule out cartilage repair as well as to assess the lower extremity for malalignment. Imaging includes weightbearing anteroposterior views in full extension; posterior–anterior (Rosenberg) views in mild flexion; lateral and patellofemoral views; and a full-length hip-to-ankle radiograph.

High-resolution (1.5 Tesla and greater) MRI is a reliable means to evaluate articular cartilage defects. The recent introduction of cartilage-specific imaging protocols has dramatically improved the quality of MRI scans and allows noninvasive monitoring after cartilage repair procedures (see Figure 1).16,17

Indications for Cartilage Repair

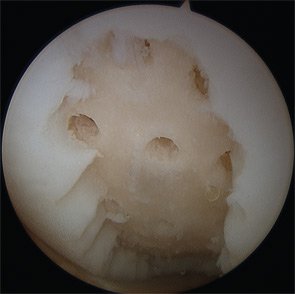

Many cartilage defects are asymptomatic; therefore, careful assessment of other potential pain generators is critical prior to consideration of surgical treatment. Nonoperative treatment with rehabilitation, activity modification, and antiinflammatory therapy should be considered for at least six months, especially for patellofemoral defects that typically respond well to a physical therapy regimen. Young patients with large defects are an exception to this recommendation, since lesion growth can occur even with symptomatic improvement from nonoperative treatment, potentially worsening the structural problem. For example, the majority of young patients experience almost complete resolution of knee pain following the removal of a loose osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) fragment; however, if the defect is left empty, 50% to 80% will develop radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis after eight to 10 years.18,19

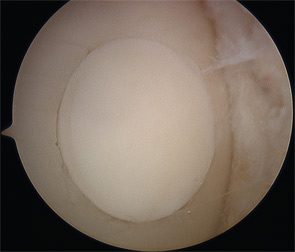

Surgical intervention is considered after establishing that the patient’s symptoms are consistent with a full-thickness (Outerbridge Grade 3 or 4) cartilage defect, and adequate nonoperative management has failed to provide acceptable pain relief. Extensive counseling about the long recovery period after cartilage repair is important to avoid unrealistic expectations and disappointment.