The use of osteochondral allografts is a logical extension of the OAT procedure. Similarly, cylinders of bone and cartilage are implanted to the damaged area. Due to the use of a donor source, larger grafts can be utilized than could be harvested from the patient’s own knee. Long-term studies have demonstrated survival of the transplanted chondrocytes, which appear to be immune privileged.38,39 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration and American Association of Tissue Banks (AATB) regulate the procurement, handling, and testing of donor tissue to minimize the risk of disease transmission, currently estimated at approximately 1 in 1.6 million.40 Osteochondral allograft transplantation is indicated for larger chondral and osteochondral lesions, particularly when the accompanying bone loss is greater than 6 mm, as well as a revision procedure after prior failed cartilage repair.34,35,41 Prolonged-fresh refrigerated tissue is the current standard, because freezing and freeze-drying devitalizes the tissue.40,42 Refrigerated tissue maintains up to 98% chondrocyte viability for one week, which decreases to 70% by one month.43,44 Size, side, and compartment matched grafts are preferred to facilitate restoration of the articular surface geometry. Cylindrical osteochondral plugs are most commonly used (see Figure 4), and in a majority of cases, press-fit fixation without the use of screws or pins is sufficient.35 Eventually, the bone is replaced through creeping substitution, while the articular cartilage remains allogeneic. Failure usually results from unsuccessful osseous integration and subsequent subchondral collapse.38 Rehabilitation includes touch-down weight bearing for six to 12 weeks depending on the location and size of the graft.

Articular Comorbidities Malalignment

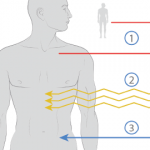

Malalignment frequently accompanies articular cartilage defects, and has been determined as both an independent risk factor for the development (odds ratio [OR] 2.06), as well as the progression (OR 4.09) of osteoarthritis.45,46 Therefore, it stands to reason that restoration of a neutral biomechanical environment is an important factor contributing to the success of any cartilage repair procedure. Patients with a femoral condyle cartilage defect whose mechanical axis is outside the neutral zone bordered by the tibial spines should have an osteotomy.47 High tibial osteotomy (HTO) for varus malalignment and distal femoral osteotomy (DFO) for valgus malalignment are the most common methods to correct malalignment. Overcorrection with a proximal tibial osteotomy, while beneficial for advanced degenerative joint disease, is not well tolerated by the younger patients that typically experience isolated articular cartilage defects. Therefore, correction to a neutral alignment with a mechanical axis falling centrally between the tibial spines is recommended. Overcorrection by shifting the axis more into the contralateral compartment is indicated only if there are arthritic changes in the joint.

Patellar Maltracking

Patellofemoral pain and/or instability are common causes of anterior knee pain, and most of these patients respond well to nonoperative measures. A limited number will be diagnosed with symptomatic cartilage defects that require surgical intervention, and both autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) and osteochondral allograft have demonstrated good outcomes; however, ACI has more positive outcomes for bipolar lesions.48,49 The goal of PF procedures is to optimize the environment for the cartilage implant, and commonly include the use of osteotomy to anteromedialize the tibial tubercle, thus reducing the contact forces across the patellofemoral joint.50 Results of PF cartilage restoration done without optimization of the PF environment are generally poor, yet using the same cartilage restoration technique with attention to PF stress has better outcomes.51,52

Meniscal Deficiency

Meniscal tears are the most common surgically treated pathology of the knee joint. Recently, there has been an increased interest in the preservation of meniscal tissue through meniscal repair, rather than meniscectomy, though some tears are found to be irreparable and substantial amounts of tissue are removed. Biomechanical studies have shown that segmental loss of meniscal tissue with disruption of the circumferential hoop bundles at any location results in biomechanical loss of that entire hoop.53 For example, both segmental loss to the capsule or a posterior horn-root tear have the same biomechanical consequence as a subtotal meniscectomy. Based on in vitro studies, most cartilage restoration algorithms treat the meniscus remnant as dysfunctional if less than a 5-mm continuous intact rim is present. The effect of meniscal tissue loss is evident more rapidly in the lateral compartment, but over time the medial compartment articular cartilage begins to break down in a large percentage of patients. Meniscal allograft transplantation decreases the stresses in a compartment with meniscal loss, and studies have reported potential chondroprotective effects with slowing, but not complete cessation of chondral degeneration.54-57 The deleterious natural history of meniscectomy and the positive effects of meniscal transplantation support the addition of meniscal transplantation to articular cartilage repair whenever substantial meniscal loss has occurred. Two prospective case series have demonstrated the positive effects of performing the two techniques concomitantly.58,59

Case Example

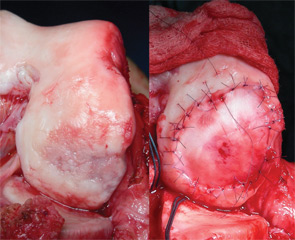

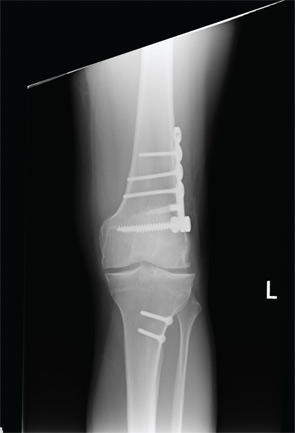

A healthy 24-year-old male presented to the office with a six-month history of persistent left lateral knee pain without recent trauma. Approximately six years previously, he had undergone arthroscopic resection of a lateral meniscal tear sustained while playing basketball. He had recovered uneventfully from surgery and return to unrestricted activities. He recently noticed increased pain and swelling, first only with impact activities, now persistently even with activities of daily living. His physical examination demonstrated a moderate effusion, mild valgus alignment of the left lower extremity, full strength, and stable ligaments. Imaging studies confirmed mild valgus alignment, minimal lateral osteophytes, and joint space narrowing (see Figure 5). An arthroscopy was performed that demonstrated subtotal lateral meniscectomy and a large chondral defect of the lateral femoral condyle. He underwent autologous chondrocyte implantation to a 10.5-cm2 defect (see Figure 6, above) in combination with lateral meniscal allograft transplantation and distal femoral osteotomy to neutralize his alignment (see Figure 7, p. 32). Postoperatively, he was kept touch-down weight bearing for eight weeks and used a CPM machine for six weeks, six hours per day. He is now two years out from surgery and is functioning well without pain or swelling with activities of daily living.