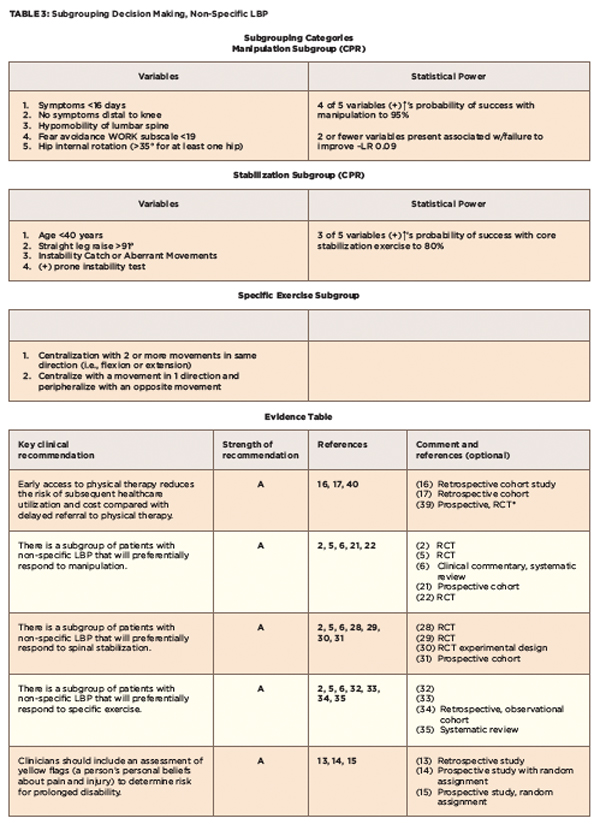

TBC Category 2: Stabilization Subgroup

Spinal instability is considered one of the important causes of low back pain, but is poorly defined and not well understood. Core stabilization exercises have become extremely popular for those with LBP, but are not the solution for all categories of LBP. This subgroup has to be identified primarily through physical examination findings.

Typically, this patient reports a “catching” sensation in the lumbar spine with change of trunk position (e.g., sit to stand, sit to lying). The examiner may also find aberrant movements during flexion/extension. For example, the patient cannot return to an erect position from flexion without use of hands on thighs (thigh walking).

It is recognized that functional instability (see Table 4) can exist in the absence of radiological evidence of spinal instability (e.g., spondylolisthesis, movement on flexion-extension films).24,25 The validity of radiographic evidence of excessive motion between vertebrae has been questioned on the basis of studies showing wide inter-individual and intra-individual variations in spinal motion characteristics in asymptomatic subjects, therefore making it difficult to establish thresholds identifying a spine as being unstable.6,26

Two muscle-stability systems have been identified: The global system (rectus abdominis, internal/external obliques, erector spinae) continues to gather most of the attention. However, it is the local system (transversus abdominis and multifidus) that functions as a low-load strategy that is needed for coordination and timing of movements.27 These muscles are postural control muscles needed for normal activities, such as sitting and standing. Evidence suggests that we need to focus on activating these muscles, because they may show loss of automatic triggering following an episode of LBP.28-30

Hicks et al identified four factors that were predictive of improvement with spinal stabilization exercises (see Tables 3, and 4).31 A preliminary clinical prediction rule was defined as positive when at least three of these factors were present; the predictive accuracy of the stabilization CPR increases the probability of success with stabilization to 80%.31

TBC Category 3: Specific Exercise Classification

This group is expected to respond preferentially to repeated end-range movements in a specific direction (flexion, extension or lateral shift). The existence of subgroups that comprise this group has been popularized by McKenzie.32 The hallmark examination criteria used in identifying patients for specific exercise is the “centralization phenomenon” (see Table 4).33,34 This involves the movement of pain from a more distal to a more proximal location. The movement producing centralization of radicular symptoms determines the directional preference (see Table 4).35,36 It is possible to have a directional preference without experiencing centralization of symptoms when a more comfortable position is experienced. The basic premise advocated for treating patients in a specific exercise classification is to use repeated end-range movements in the direction that caused centralization or diminished pain.