Image Credit: JPC-PROD/shutterstock.com

Low back pain (LBP) is one of the most common reasons for physician appointments. However, treatment results remain suboptimal, resulting in high rates of chronic pain, narcotic usage, surgery, depression and disability—all at great cost to individuals and the nation. One reason for this is the current practice of grouping all low back pain patients without a specific etiologic diagnosis into the single nebulous category of “non-specific LBP,” for which the evidence base does not support any specific treatment. This methodological flaw has perpetuated the notion that no intervention is superior to the passage of time.5 Recent evidence reflects the need for categorizing non-specific LBP into distinct subgroups and, thus, direct treatment that will likely produce favorable results.

The purpose of this clinical commentary is to introduce and describe an LBP classification system that focuses on non-specific LBP that points to specific treatment pathways and to discuss the impact of early access to physical therapy on this patient population.

Introduction

According to recent studies, just about everyone reading this article will experience at least one episode of low back pain during their lifetime. Perhaps even more disturbing is that although many do indeed “recover on their own,” an estimated 60–85% of those individuals will have a recurrence.1 LBP is the fifth most common reason for all physician visits in the U.S.3 It’s also the most common problem seen in physical therapy clinics.4

Chou defines non-specific LBP as, “LBP that cannot reliably be attributed to a specific disease or spinal abnormality”; 85% of LBP patients fall into this category.3 Fritz and colleagues concluded, “nonspecific LBP is not a homogenous entity, but instead consists of subtypes, or classifications, that can be identified based on specific signs and symptoms.”5,6

Treatment-Based Classification System

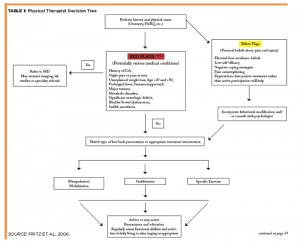

A promising classification system that has gained popularity is the Treatment-Based Classification System (TBC), which is based on the original work of Delitto and colleagues in 1995.6-8 This approach uses information gathered from the physical examination and from patient self-reports of pain (10-point pain scale and pain diagram) and disability (modified Oswestry questionnaire, see Figure 1). This information allows patient subgrouping, which then guides patient treatment.6-9 This system combines and modifies different schools of thought into a more practical, evidence-based system.

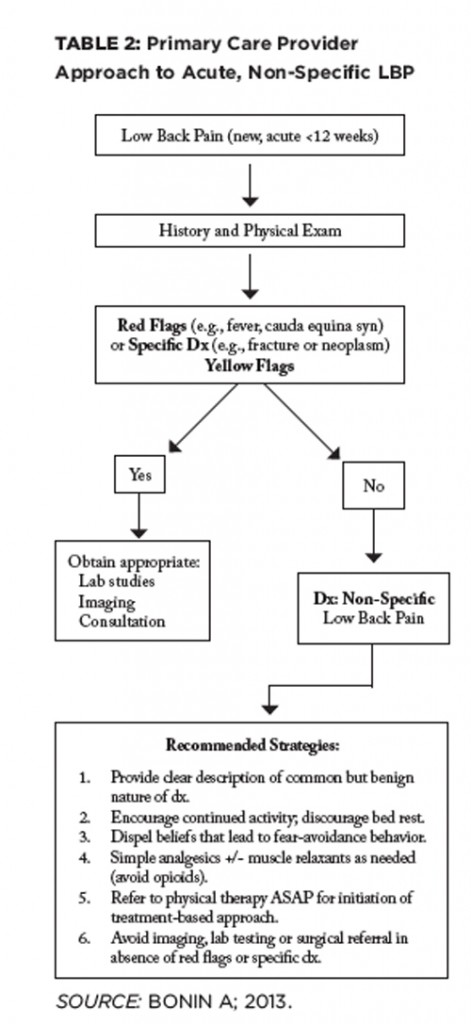

Using this system, patients are screened for both red and yellow flags. Red flags are associated with serious medical conditions that can mask as musculoskeletal pain (see Table 1).10-12 Yellow flags are believed to represent psychological barriers that may delay recovery.

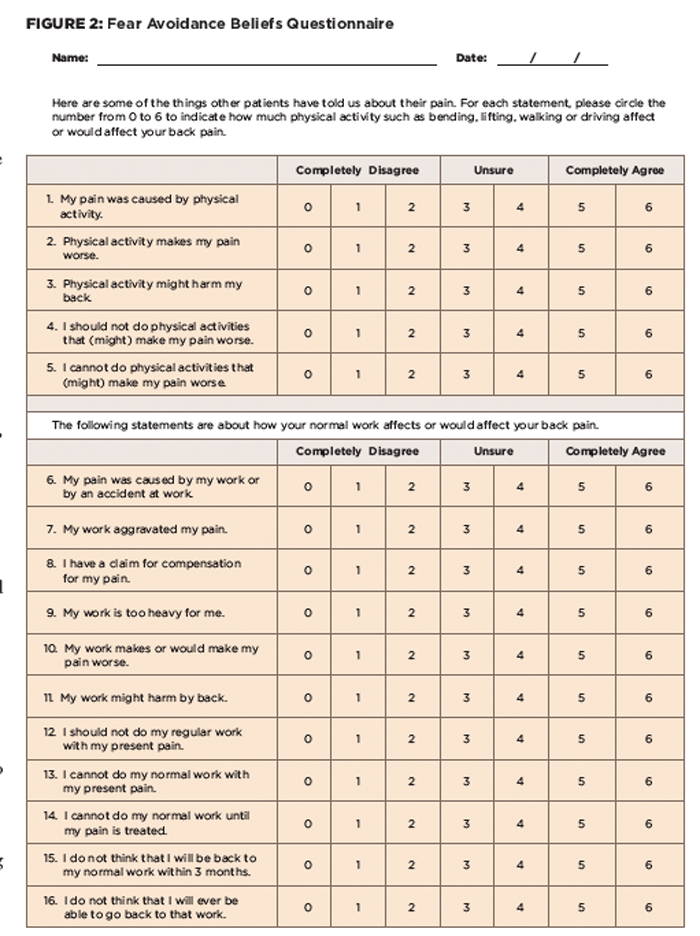

According to Fritz and colleagues, “fear-avoidance beliefs [see Figure 2] are present in patients with acute LBP, and may be an important factor in explaining the transition from acute to chronic conditions.”13-15 Fear-avoidance beliefs are established early in the course of a pain experience and serve no protective purpose.15 Many believe that fear-avoidance beliefs, specifically about work, are the psychosocial factors that could best be used to predict return to work in patients with acute work-related LBP.13-15

There is strong evidence that once a worker has been out of work for four to 12 weeks, they have a 10–40% risk (depending on the setting) of remaining off work at least one year. After one to two years’ absence, it is unlikely they will return to any form of work, irrespective of further treatment.15

(click for larger image)

Figure 2: Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire

This screening is typically done during initial physical therapy evaluation, but can also be done by the primary care provider (see Table 2).

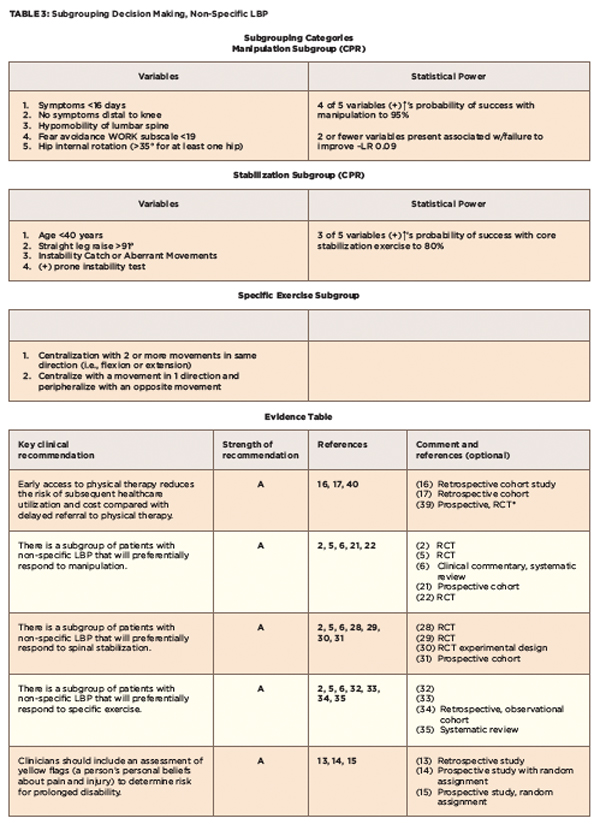

Although patients with LBP are commonly referred to physical therapy, the referral is often delayed. A number of studies have shown that early access to physical therapy (within 30 days) by patients with LBP actually improved patient outcomes. Early access was associated with decreased utilization of advanced imaging, decreased additional physician visits, and fewer surgeries, injections and opioid medications.16-20

After information is gathered from self-reported measures, the history and a thorough physical examination, patients are allocated into one of four subgroups: manipulation, stabilization, specific exercise (flexion, extension and lateral-shift patterns) and traction. Each subgroup is named for the primary treatment that the patients would receive once assigned.

TBC Category 1: Manual Therapy Subgroup

This subgroup is believed to respond favorably to manipulation and/or mobilization of the lumbar spine or sacroiliac joint. Evidence suggests that patients who fall into this subgroup generally have a shorter duration of symptoms (<16 days), at least one level of hypomobility (segmental stiffness) of the lumbar spine and symptoms that don’t extend beyond the knee.21

A prospective, cohort study by Flynn et al was carried out with the objective of developing a clinical prediction rule (CPR) to identify patients with non-specific LBP who would improve with spinal manipulation. The CPR includes five variables (see Table 3); when four of these five variables were present, patients were very likely to improve (positive likelihood ratio, 24), increasing the probability of success with manipulation from 45–95%, and the presence of two or fewer variables was almost always associated with a failure to improve (negative likelihood ratio, 0.09). This CPR has been validated by a randomized controlled trial.22

There is strong evidence that once a worker has been out of work for four to 12 weeks, they have a 10–40% risk (depending on the setting) of remaining off work at least one year. After one to two years’ absence, it is unlikely they will return to any form of work, irrespective of further treatment.

Many commentators continue to believe that there is a lack of evidence supporting the efficacy of manual treatment (spinal manipulation/mobilization) on LBP.23 However, most studies have not used homogenous samples, and thus, patients who may indeed benefit by spinal manipulation/mobilization are grouped with others who likely would not benefit. Researchers are now challenging this myth with subgrouping methods to maximize treatment outcomes.

TBC Category 2: Stabilization Subgroup

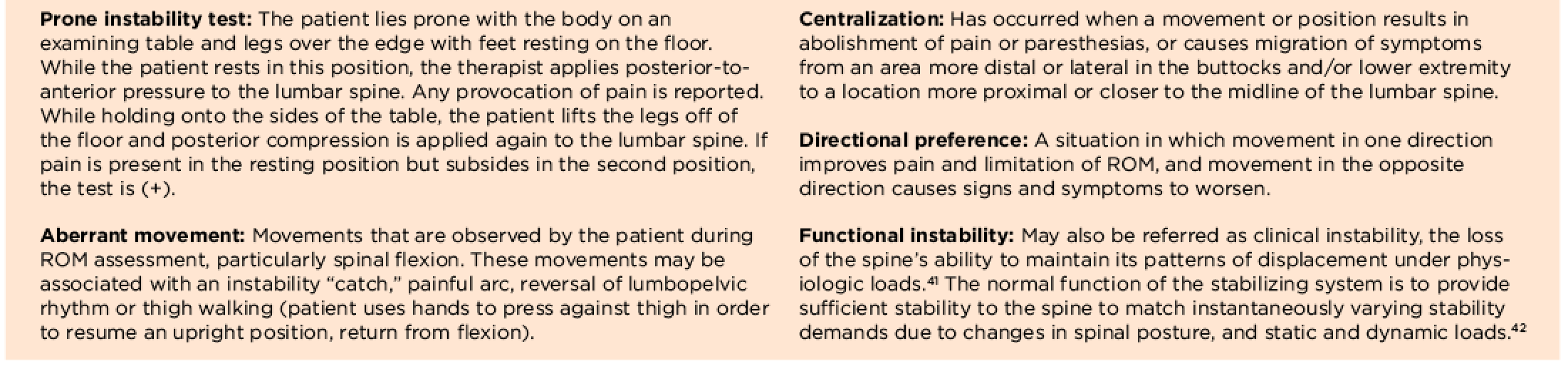

Spinal instability is considered one of the important causes of low back pain, but is poorly defined and not well understood. Core stabilization exercises have become extremely popular for those with LBP, but are not the solution for all categories of LBP. This subgroup has to be identified primarily through physical examination findings.

Typically, this patient reports a “catching” sensation in the lumbar spine with change of trunk position (e.g., sit to stand, sit to lying). The examiner may also find aberrant movements during flexion/extension. For example, the patient cannot return to an erect position from flexion without use of hands on thighs (thigh walking).

It is recognized that functional instability (see Table 4) can exist in the absence of radiological evidence of spinal instability (e.g., spondylolisthesis, movement on flexion-extension films).24,25 The validity of radiographic evidence of excessive motion between vertebrae has been questioned on the basis of studies showing wide inter-individual and intra-individual variations in spinal motion characteristics in asymptomatic subjects, therefore making it difficult to establish thresholds identifying a spine as being unstable.6,26

Two muscle-stability systems have been identified: The global system (rectus abdominis, internal/external obliques, erector spinae) continues to gather most of the attention. However, it is the local system (transversus abdominis and multifidus) that functions as a low-load strategy that is needed for coordination and timing of movements.27 These muscles are postural control muscles needed for normal activities, such as sitting and standing. Evidence suggests that we need to focus on activating these muscles, because they may show loss of automatic triggering following an episode of LBP.28-30

Hicks et al identified four factors that were predictive of improvement with spinal stabilization exercises (see Tables 3, and 4).31 A preliminary clinical prediction rule was defined as positive when at least three of these factors were present; the predictive accuracy of the stabilization CPR increases the probability of success with stabilization to 80%.31

TBC Category 3: Specific Exercise Classification

This group is expected to respond preferentially to repeated end-range movements in a specific direction (flexion, extension or lateral shift). The existence of subgroups that comprise this group has been popularized by McKenzie.32 The hallmark examination criteria used in identifying patients for specific exercise is the “centralization phenomenon” (see Table 4).33,34 This involves the movement of pain from a more distal to a more proximal location. The movement producing centralization of radicular symptoms determines the directional preference (see Table 4).35,36 It is possible to have a directional preference without experiencing centralization of symptoms when a more comfortable position is experienced. The basic premise advocated for treating patients in a specific exercise classification is to use repeated end-range movements in the direction that caused centralization or diminished pain.

The directions that patients may show a preference for are extension, flexion and lateral shift. Extension is the most common direction used; these responders tend to be younger in age and present with acute symptoms.6,35,36 The flexion-specific subgroup appears to be less common and most likely occurs in patients who are older and, often, with a medical diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis.6,36 The third movement direction classification is a lateral shift, which is considerably less common than flexion or extension categories and may represent more complex anatomic or functional situations.35,36

TBC Category 4: Traction Classification

Patients matched to this group are expected to have radicular symptoms, signs of nerve root compression and the absence of centralization with movement testing. The use of mechanical traction in the management of patients with acute or chronic LBP has generally not been endorsed by evidence-based practice.37,38 However, Fritz et al have provided some support for this approach in a randomized controlled trial that identified a subgroup of patients who are likely to respond to traction. Results of this study suggest this subgroup is characterized by the presence of leg symptoms and signs of nerve root compression, but also either peripheralization with extension movements or a positive crossed straight leg raise test.39

Additional research is needed to further define this subgroup of traction responders, as well as studies to define parameters that will maximize any treatment effect (e.g., traction force, duration and patient position).

Final Comments

The majority of patients presenting with LBP cannot be diagnosed with a specific etiology, thus falling into the category of non-specific low back pain. When considering the rising cost of managing LBP and the attendant levels of disability, we can no longer afford to drive treatment decisions based on ineffective traditional approaches.

The treatment-based classification described above is a viable option that may assist practitioners in categorizing patients into better defined subgroups with recommended treatments likely to improve outcomes. Subgrouping patients with non-specific LBP, as well as early access to physical therapy, appears to be a more effective way to manage this most challenging condition.

Emma W. White, PT, DPT, OCS, is an assistant professor at Winston-Salem State University-Department of Physical Therapy, N.C. Prior to this academic appointment, she owned and managed an orthopedic outpatient physical therapy practice, Thomasville Physical Therapy (October 1991–April 2008). Dr. White has more than 30 years of clinical practice experience. She received her physical therapy degree from the Medical College of Virginia in 1978 and a doctorate degree in physical therapy from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2008.

Emma W. White, PT, DPT, OCS, is an assistant professor at Winston-Salem State University-Department of Physical Therapy, N.C. Prior to this academic appointment, she owned and managed an orthopedic outpatient physical therapy practice, Thomasville Physical Therapy (October 1991–April 2008). Dr. White has more than 30 years of clinical practice experience. She received her physical therapy degree from the Medical College of Virginia in 1978 and a doctorate degree in physical therapy from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2008.

Andy Bonin is a medical director for Blue Cross & Blue Shield of North Carolina’s Department of Appeals, and an assistant consulting professor at Duke University School of Medicine, teaching in the Family Medicine Residency Program. He has more than 35 years of clinical practice experience, since graduating from Duke Medical School in 1975. He is board certified in Family Medicine and has a Certificate of Added Qualification in Sports Medicine. He is a regular provider of free medical care in the Open Door Clinic of Wake Co. Urban Ministries and the TROSA Clinic in Durham. He is also a Certified Professional Coder.

Andy Bonin is a medical director for Blue Cross & Blue Shield of North Carolina’s Department of Appeals, and an assistant consulting professor at Duke University School of Medicine, teaching in the Family Medicine Residency Program. He has more than 35 years of clinical practice experience, since graduating from Duke Medical School in 1975. He is board certified in Family Medicine and has a Certificate of Added Qualification in Sports Medicine. He is a regular provider of free medical care in the Open Door Clinic of Wake Co. Urban Ministries and the TROSA Clinic in Durham. He is also a Certified Professional Coder.

References

- Luo X, Pietronbon R, Sun SX, et al. Estimates and patterns of direct health care expenditures among individuals with back pain in the United States. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004 Jan 1;29(1):79–86.

- Brennan GP, Fritz JM, Hunter SJ, et al. Identifying subgroups of patients with acute/subacute “nonspecific” low back pain: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006 Mar 15;31(6):623–631.

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: A Joint Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Oct 2;147(7):478–491.

- Jette AM, Delitto A. Physical therapy episodes of care for patients with low back pain. Phys Ther. 1994 Feb;74(2):101–110.

- Fritz JM, Delitto A. Erhard DC. Comparison of classification based physical therapy with therapy based on clinical practice guidelines for patients with acute low back pain: A randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003 Jul 1;28(13):1363–1372.

- Fritz JM, Cleland JA, Childs JD. Subgrouping patients with low back pain: Evolution of a classification approach to physical therapy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007 Jun;37(6):290–302.

- Fritz JM, Georges S. The use of a classification approach to identify subgroups of patients with acute low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000; 25(1):106–114.

- Delitto A, Erhand RE, Bowling RW. A treatment‐based classification approach to low back syndrome: Identifying and staging patients for conservative treatment. Phys Ther. 1995 Jun;75:470–489.

- Brennan GP, Fritz JM, Hunter SJ, et al. Identifying subgroups of patients with acute/subacute ‘nonspecific’ low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006 Mar 15;31(6):623–631.

- Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM. A systematic review identifies five ‘red flags’ to screen for vertebral fracture in patients with low back pain. J Clin Epidemiol. Feb;61(2):110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.04.013.

- Leerar PJ, Boissonnault W, Domholdt E, et al. Documentation of red flags of physical therapists for patients with low back pain. J Man Manip Ther. 2007;15(1):42–49.

- New Zealand Acute LBP Guide. New Zealand Guidelines Group.

- Cleland JA, Fritz JM, Brennan GP. Predictive validity of initial fear avoidance beliefs in patients with low back pain receiving physical therapy: Is the FABQ a useful screening tool for identifying patients at risk for a poor recovery? Eur Spine J. 2008 Jan;17(1):70–79.

- Fritz JM, George SZ. Identifying psychological variables in patients with acute work-related low back pain: The importance of fear-avoidance beliefs. Phys Ther. 2002 Oct;82(10):973–983.

- Fritz JM, George SZ, Delitto A. The role of fear-avoidance beliefs in acute low back pain: Relationships with current and future disability and work status. Pain. 2001 Oct;94(1):7–15.

- Gelhorn AC, Chan L, Martin B, et al. Management patterns in acute low back pain: The role of physical therapy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012 Apr 20;37(9):775–782.

- Fritz JM, Childs JD, Wainner RS, et al. Primary care referral of patients with low back pain to physical therapy: Impact on future health care utilization and costs. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012 Dec 1;37(25):2114–2121.

- Nordemann L, Nilsoon B, Moller M, et al. Early access to physical therapy treatment for subacute low back pain in primary healthcare: A prospective randomized clinical trial. Clin J Pain. 2006 Jul–Aug;22(6):505–511.

- Gatchel RJ, Polatin PB, Noe C, et al. Treatment and cost-effectiveness of early intervention for acute low back pain patients: One-year prospective study. J Occup Rehabil. 2003 Mar;13(1):1–9.

- Pinnington MA, Miller J, Stanley I. An evaluation of prompt access to physiotherapy in the management of low back pain in primary care. Fam Pract. 2004 Aug;21(4):372–380.

- Flynn T, Fritz JM, Whitman J, et al. A clinical prediction rule for classifying patients with low back pain who demonstrates short-term improvement with spinal manipulation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002 Dec 15;27(24):2835–2843.

- Childs JD, Fritz JM, Flynn TW, et al. A clinical prediction rule to identify patients with low back pain most likely to benefit from spinal manipulation: A validation study. Ann Intern Med. 2004 Dec 21;141(12):920–928.

- Casazza BA. Diagnosis and treatment of acute low back pain. Am Fam Physician. 2012 Feb 15;85(4):343–350.

- Alqarni AM, Schneiders AG, Hendrick PA. Clinical tests to diagnose lumbar segmental instability: A systematic review. J Orthop & Sports Phys Ther. 2011 Mar;41(3):130–140.

- Cook C, Brismee JM, Sizer PS Jr. Subjective and objective descriptors of clinical lumbar instability: A Delphi study. Man Ther. 2006 Feb;11(1):11–21.

- Hayes MA, Howard TC, Gruel CR, et al. Roentgenographic evaluation of lumbar spine flexion‐extension in asymptomatic individuals. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1989 Mar;14(3):327–331.

- Bergmark A. Stability of the lumbar spine. A study in mechanical engineering. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1989;230:1–54.

- Hides JA, Richardson CA, Jull GA. Multifidus muscle recovery is not automatic after resolution of acute, first-episode low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996 Dec 1;21(23):2763–2769.

- Hides JA, Jull GA, Richardson CA. Long-term effects of specific stabilizing exercises for first‐episode low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001 Jun 1;26(11):E243–E248.

- Hodges PW, Richardson CA. Delayed postural contraction of transversus abdominis in low back pain associated with movement of the lower limb. J Spinal Disord. 1998 Feb;11(1):46–56.

- Hicks GE, Frit JM, Delitto A, et al. Preliminary development of a clinical prediction rule for determining which patients with low back pain will respond to a stabilization exercise program. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005 Sep;86(9):1753–1762.

- McKenzie RA. The Lumbar Spine: Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy. Waikanae, New Zealand: Spinal Publications Ltd, 1989.

- Fritz JM, Delitto A, Vignovic M, et al. Interrater reliability of judgments of the centralization phenomenon and status change during movement testing in patients with low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000 Jan;81(1):57–61.

- Werneke MW, Hart DC, Resnik L, et al. Centralization: Prevalence and effect on treatment outcomes using a standardized operational definition and operational method. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008 Mar;38(3):116–125.

- Aina A, May S, Clare H. The centralization phenomenon of spinal symptoms—A systematic review. Man Ther. 2004 Aug;9(3):134–143.

- Long A, Donelson R, Fung T. Does it matter which exercise? A randomized control trial of exercise for low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004 Dec 1;29(23):2593–2602.

- Clarke J, van Tulder M, Blomberg S, et al. Traction for low back pain with or without sciatica: An updates systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane collaboration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006 Jun 15;31(14):1591–1599.

- Werners R, Pynsent PB, Bulstrode CJ. Randomized trial comparing interferential therapy with motorized lumbar traction and massage in the management of low back pain in a primary care setting. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999 Aug 1;24(15):1579–1584.

- Fritz JM, Lindsay W, Matheson JW, et al. Is there a subgroup of patients with low back pain likely to benefit from mechanical traction? Results of a randomized clinical trial and subgrouping analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007 Dec 15;32(26):E793–E800.

- Nordeman TH, Nilsson B. Möller M et al. Early access to physical therapy treatment for subacute low back pain in primary care. Clin J Pain. 2006 Jul–Aug;22(6):505–511.

- Panajabi MM. Clinical spinal instability and low back pain. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2003 Aug;13(4):371–379.

- Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part I. Function, dysfunction, adaptation, and enhancement. J Spinal Disord. 1992 Dec;5(4):383–389.