She turned the page. “After that, well, we tried different combinations of oral antibiotics and supplements. The theory, well, you may already know this, but the Lyme spirochete, it’s a type of bacteria, evades the immune system. That’s when he recommended the intravenous antibiotic—let me make sure I say this right—ceftriaxone.”

My head was spinning. An embedded tick promptly treated with the appropriate dose of doxycycline, two negative Lyme tests, and a boatload of antibiotics later, and we’re still focused on Lyme disease?

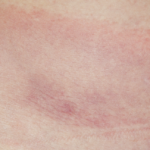

She resumed: “During the first four months of antibiotic treatment, I thought I was turning the corner, but then almost overnight the swelling in my knee doubled. The tick was fighting back. My short-term memory was shot. My mood swings were horrific. And the fatigue—I could barely will myself out of bed each morning. My veins were blown. I was losing the battle. That’s when Dr. F. recommended that I have a port placed.” She reached up and ran her finger over the upper right chest where an egg-sized implant was palpable beneath the skin.

Ports are often used in cancer patients when monthly chemotherapy is required, but this was the first time I’d seen one in a patient with presumed Lyme disease.

“Once the port was in, he doubled the dose of the IV ceftriaxone. It was a last-ditch effort, but it wasn’t enough. I lost my job and applied for disability—that would be four months ago.”

“I’m sorry it came to that,” I replied. I scanned the Lyme Disease Symptom Checklist hanging limply from my hand. In a matter of 20 minutes I had acquired more than half of the symptoms. I maintained an even tone. “You’ve been through a lot.” I reached into the cabinet above the sink and unfolded a cloth gown. “Let me step out for a minute while you change. You can keep your underclothes on, but I want to do a complete examination. I’ll be back in a few minutes.”

About Lyme

Back in my office, I slumped into my swivel chair and drifted back to a simpler time. Years ago, as a visiting internal medicine resident at Yale New Haven Hospital, I rotated through the department of Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology. Yale, and more specifically Allen Steere, MD, was considered ground zero in the emerging Lyme epidemic. In 1975, two local women from the nearby town of Lyme, Conn., Polly Murray and Judith Mensch, contacted the Connecticut State Health Department. Both of their children had been diagnosed with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), and they knew of other children and adults in the small community with similar symptoms. Because JRA is an uncommon immune system disease affecting about one in 1,000 children, and the initial reports suggested an unexplained cluster, Dr. Steere at the Yale Department of Rheumatology met with them to investigate further.