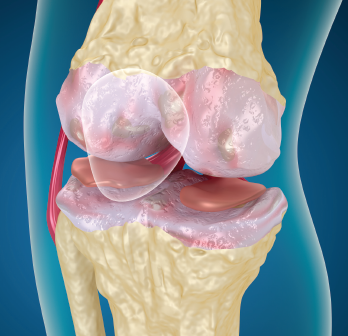

Osteoarthritis of the knee

Alex Mit / shutterstock.com

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) accounts for more than 80% of OA disease burden and has doubled in prevalence in the mid-20th century in the U.S. when compared with people who lived during early industrial era (1800s to early 1900s).1 Currently, the diagnostic and treatment armamentaria are limited. Disease progression is measured by joint space narrowing on plain X-ray. Physical therapy and pain medication are treatment mainstays, and joint replacement may follow years of pain and disability. But what if clinicians could predict disease progression and initiate targeted treatments much earlier in the course of the disease?

Three years ago, an international and multidisciplinary group concluded its first-phase work to identify reliable biomarkers for assessing disease progression and treatment response in knee osteoarthritis. PROGRESS OA, an effort of the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) Biomarkers Consortium, has just advanced to Phase 2. The goal, according to lead investigators, is to expand the diagnostic toolbox beyond the current gold standard of plain X-rays. During Phase 2 of the project, the research team will validate the highest performing imaging and biochemical markers identified during the first phase, hopefully creating a more enabling pathway for clinical trials in new drug development.

The FNIH Approach

In sheer numbers, OA accounts for a larger disease burden than rheumatoid arthritis (RA). But OA has not lent itself to elucidating pathways affecting disease that have led to advances in RA treatment, says Joseph Menetski, PhD, FNIH associate vice president of research partnerships.

For drug development to progress, regulatory agencies require reliable and valid study endpoints. That’s been difficult in OA, he says, because it takes years to assess damage with plain X-rays and there tends to be heterogeneity of symptoms. The challenge is to come up with reliable indicators of disease progression. What distinguishes the FNIH Biomarkers Consortium approach, Dr. Menetski says, is that the project includes stakeholders who will be conducting trials.

“Right from the beginning, we have input from people who will use the markers in drug development,” he says. “Our projects are identified, designed and developed by the people who actually need these tools.”

A Pathway to Trials

Accessing the data collected from the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) sample set, funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), the FNIH Biomarkers Consortium team has been working on two fronts: biochemical markers and imaging markers. Virginia Kraus, MD, PhD, professor, Departments of Medicine, Pathology and Orthopedic Surgery, Duke University School of Medicine, as well as a faculty member of the Duke Molecular Physiology Institute, oversees the biochemical marker aspects of the project. The team was in “the enviable position,” she reports, to access biospecimens collected over a seven-year period.

“We were able to pick individuals from the OAI sample set who would be most appropriate for testing the hypothesis that we could use both imaging and biochemical markers to identify people at highest risk for pain and X-ray progression,” Dr. Kraus says.

David Hunter, MBBS (Hons), MSc (Clin Epi), M SpMed, PhD, FRACP (Rheum), Florance and Cope Chair of Rheumatology, chair of the Institute of Bone and Joint Research, and professor of medicine at the University of Sydney, Australia, has directed the push to refine disease progression using MRI. “It’s important to conceptualize the fact that osteoarthritis is not just a disease of one tissue,” he says. “Osteoarthritis affects the whole joint organ, and any tissue within the joint can be affected, and that obviously includes the synovium, but also cartilage, meniscus, bone, ligaments, capsule and muscle. And we’re trying to use whole joint methods to assess the structural changes, particularly on MRI.”

The group is using semi-quantitative methods to assess all of the joint tissue structures. From one nested case-control study, authors found that MRI-detected pathologies, such as bone marrow lesions and meniscal and cartilage damage, were more severe in the case study group, suggesting that early changes are associated with risk of both radiographic worsening and progression of symptoms.2 “We want to advocate for the use of MRI and biochemical markers as research tools for clinical trials,” he says, because it takes a long time to demonstrate change on plain radiographs.

For some time, researchers have been aware of the markers that indicate cartilage degradation or synthesis, as well as bone turnover, but the challenge is to validate these markers and turn them into decision-making tools, says Dr. Menetski. Conducting such validation studies in phases makes sense, because this allows researchers to narrow their focus and partners to fund the most promising and practical techniques. The idea, he continues, is that qualified markers will spur activity within the pharmaceutical and biotech sectors to find treatments to arrest the progress of damage in knee OA.