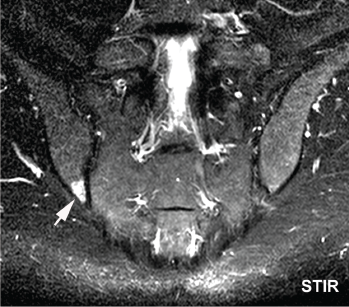

Bone marrow edema in the inferior posterior ilium, the single most affected SIJ region in athletes, is shown.

Researchers in Demark studied joints of young adult athletes to better understand the difference in bone marrow edema common in healthy people vs. what is experienced by patients with spondyloarthritis, a serious inflammatory condition of the spine and sacroiliac joints.

Early recognition of spondylo-arthritis can be tricky because it can be confused with symptoms and imaging results also seen in people with mechanical back pain and in healthy young adults, according to principal investigators Ulrich Weber, MD, King Christian 10th Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases in Graasten, Denmark, and Søren Schmidt-Olsen, MD, North Denmark Regional Hospital, Hjørring, Denmark. The study, published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, analyzed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans from healthy athletes to look for normal ranges of bone marrow edema, which is characterized by cellular infiltrates and excess fluid in the bone.1

Once considered the single hallmark of sacroiliitis, bone marrow edema was found to be common in these young healthy athletes who did not have the disease, notes Dr. Weber. Therefore, physicians should use caution when interpreting MRI results to avoid mistaking possible signs of mechanical strain for spondyloarthritis, a much rarer occurrence in the general population.

Dr. Weber

“The problem is that mechanical back pain occurs as a lifetime prevalence in more than two-thirds of all people,” says Dr. Weber. “Chronic back pain is a very common disorder in industrialized countries and a leading reason for disability.”

Early axial spondyloarthritis affects young adults and is a painful inflammatory disease of the joints and spine that causes chronic low back pain. Because the sacroiliac joints are so deep in the body, the condition can be difficult to discern solely by clinical examination alone, so doctors often use MRI scans to look for sacroiliitis, inflammation of the sacroiliac joint that connects the spine to the pelvis and is the presenting feature in most patients, explains Dr. Weber.

The authors note a data-driven threshold definition of sacroiliitis is needed to reliably distinguish the lesion spectrum common to patients with early axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) from the bone marrow edema “background noise” of MRI features that can be seen in people who are healthy or have mechanical back pain. No normal reference range for MRI scans of bone marrow edema lesions in healthy young adults exists, says Dr. Weber.

“We are struggling to find what could be the correct range where we think this could still be a normal background noise or a normal reference range, not to overdiagnose spondyloarthritis,” says Dr. Weber. “We think the present proposal of two lesions is too low.”

Researchers reviewed data from MRI scans of sacroiliac joints of 20 recreational runners (12 women, eight men) and a group of 22 professional male hockey players from the Danish Premier League. All were healthy athletes ranging in age from 18 to 40 years old.

The study explored the frequency and anatomic distribution of sacroiliac joint lesions on MRI to determine the intersection between normal variation and disease. Researchers selected recreational and elite athlete groups to investigate extremes of axial skeletal strain—low intensity in the runners and maximum intensity in the professional ice hockey players, says Dr. Weber.

“We wanted to compare those two extremes and look at how many of these obviously healthy persons would be (given) a diagnosis of sacroiliitis with the current MRI definition. … So how many false positives would we create in persons with this high axial strain?” he asks.

The scans were conducted on the runners before and after a 6.2 km run and on the hockey players at the end of their sport season. Independent blinded readers analyzed the MRI data and recorded subjects who met Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) definition of active sacroiliitis. Mixed in with the reviewed data to serve as masking were seven MRI scans (with two paired images) of spondyloarthritis patients who were undergoing anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) treatment.

Descriptive analysis included the mean frequency of sacroiliac joint quadrants exhibiting bone marrow edema and structural lesions and their distribution in eight anatomic sacroiliac joint regions that involved the upper and lower ilium and sacrum, subdivided into anterior and posterior slices.

Results

Dr. Deodhar

The results indicated that bone marrow edema was common among both cohorts of healthy athletes, showing up in the MRI scans of an average of three to four joint quadrants per subject, meeting the ASAS definition of active sacroiliitis in 30–41% of study participants, Dr. Weber says. The posterior lower ilium was the single most affected sacroiliac joint region.

Joint erosion was virtually absent in the scans of study participants, yet one in three of these healthy athletes met the most widely applied classification criteria for sacroiliitis based solely on bone marrow edema, says Dr. Weber. This supports the authors’ argument that the current threshold recommended by ASAS of at least two lesions is not enough and the bar to reach diagnosis of spondyloarthritis needs to be set higher.

“If you just focus on bone marrow edema and the range (of lesions) is between two and four, then the specificity is low and, you do not see erosion, then you have to be cautious,” says Dr. Weber. “This could be mechanical strain.”

First published in a 2009 article in the Annals of Rheumatic Diseases, the ASAS classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis define a positive MRI to diagnose sacroiliitis as one bone marrow edema lesion in two consecutive MRI slices or two or more bone marrow edema lesions on a single slice.2 The 97% specificity of the imaging arm of the ASAS axial spondyloarthritis classification criteria mistakenly led some rheumatologists to believe the sacroiliac joint changes on MRI, as defined by the criteria, could be used for diagnostic purposes in clinical practice, notes rheumatologist Atul Deodhar, MD, professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Ore.

The well-designed study by Dr. Weber and colleagues adds to the growing literature that shows low-grade bone marrow edema, fulfilling the ASAS definition, is seen in 25% of healthy individuals, plus in patients with nonspecific mechanical back pain, says Dr. Deodhar.

“We can draw two conclusions from this study,” says Dr. Deodhar. “First, classification criteria should not be used for making a diagnosis, and second, the definition of positive MRI of the SI joints for discrimination of early axSpA needs to be modified by a data-driven approach.”

Dr. Weber advises rheumatologists to be cautious with the definition of active sacroiliitis when considering MRI results and to consider that isolated low-grade bone marrow edema may be insufficient to diagnose early axial spondyloarthritis. He also notes the disease is much more likely present if an MRI displays concomitant erosion and other structural lesions.

Catherine Kolonko is a medical writer based in Oregon.

References

- Weber U, Jurik AG, Zejden A, et al. Frequency and anatomic distribution of magnetic resonance imaging features in the sacroiliac joints of young athletes. Exploring ‘background noise toward a data‐driven definition of sacroiliitis in early spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 May;70(5):736–745.

- Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): Validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 Jun;68(6):777–783.