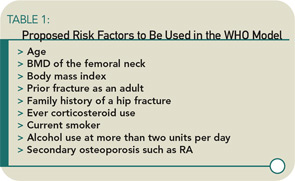

These and other issues have motivated a group of epidemiologists and clinicians who treat patients for osteoporosis to develop a new set of WHO recommendations for preventing osteoporotic fractures. The final document is not yet ready for dissemination. However, these new recommendations combine clinical risk factors that increase osteoporotic fracture risk (see Table 1) and a bone mineral density measurement—if available—to provide a 10-year risk of a hip fracture. The risk threshold used to recommend treatment may differ by country but, for the United States, hip fracture prevention treatment will be recommended if the 10-year risk is about 3%.1

Therapies: Anti-Resorptive Agents

Medications for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis currently include anti-resorptive agents (bisphosphonates, selective estrogen receptor modulators, calcitonin, and estrogen) and one anabolic agent (rhPTH 1-34 or teriparatide). (See Table 2) Physicians generally initiate therapy for patients with osteoporosis with a bisphosphonate; if the patient suffers fractures or is intolerant to the oral or intravenous bisphosphonates, rhPTH 1-34 is prescribed. Because osteoporosis is a chronic disease, physicians usually initiate treatment for patients who are around age 60 and will continue to monitor the patients bone status for another 20 to 25 years. Like patients with any other chronic disease who take a medication for a long time, osteoporosis patients ask their physicians if they need to continue the medication. Generally this happens after five or more years of weekly therapy with a bisphosphonate. This is a difficult question to answer because the clinical trials performed for FDA approval only last for three years, and information on fracture reduction after that period is not available for most of the osteoporosis agents now in use.

An extension study, Fracture Intervention Trial Long-Term Extension (FLEX), was recently published. This study addressed the duration of therapy and evaluated patients enrolled in the Fracture Intervention Study (FIT) who had been on alendronate for three years. These patients had a T score of the total hip or femoral neck of greater than -3.0 (higher than the mean at entry into the FIT trial). Nearly 1,000 women were randomized to placebo, 5 mg of alendronate a day, or 10 mg of alendronate a day for three years. Study endpoints included bone mineral density, biochemical markers of bone turnover, and incident vertebral and nonvertebral fractures.

Although study subjects were off medication for between one and two years, those randomized to the placebo lost about 2% of hip bone mass but had no decline in lumbar spine bone mass. They also had increasing CTX-1 (a marker of osteoclast activity) but no increase in morphometric vertebral fractures or nonvertebral fractures compared with the alendronate-treated subjects.2 These findings suggest that, in patients who have been treated with a bisphosphonates for more than three years, it is probably safe to discontinue the medication if they have responded well, have a T score of the total hip or femoral neck of greater than -2.5, have not experienced a low-impact fracture while on the medication, and have low risk of an osteoporotic fracture.