CHICAGO—Medications have frequently been implicated as a cause of musculoskeletal complaints, including persistent arthralgias, arthritis and myalgias.1 The list of offending agents is diverse, and the degree of symptoms is variable. In the world of transplant recipients, this list is exhaustive and includes immunosuppressive agents (cyclosporine, tacrolimus); myeloid growth factors, such as G-CSF; antibiotics (quinolones); and antifungal drugs (voriconazole).

Additional etiologies for musculoskeletal complaints may include hyperuricemia and gouty arthritis, osteoporosis, aseptic necrosis of the femoral head and septic arthritis.

Calcineurin inhibitor pain syndrome (CIPS) is a rare syndrome, characterized by symmetric lower extremity arthralgias and long bone pain, seen among patients currently on treatment with calcineurin inhibitors.

Below, we discuss the case of a patient who presented with bilateral symmetric knee pain while on cyclosporine. Our case highlights the importance of keeping CIPS on the differential diagnosis when a transplant recipient presents with arthralgias and bone pain. It also elucidates the challenges of treating this entity.

Case Report

A 53-year-old man who had received a liver transplant for a diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhosis was referred to the rheumatology clinic for unremitting knee and lower extremity pain, fatigue and myalgias.

Approximately one month after his transplant, he complained of polyarthralgia, predominantly affecting the large joints (shoulders, knees, back and ankles), for which he had been treated with prednisone. Consequently, most of his arthralgias resolved, except for persistent knee pain.

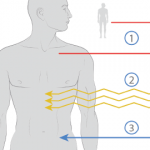

He was then evaluated at his primary care physician’s office, where a physical examination revealed bilateral crepitus in his knees. Knee X-rays showed evidence of bilateral, medial joint space narrowing (see Figures 1 and 2). An initial diagnosis of osteoarthritis was made, and he was referred to physical therapy for quadriceps strengthening.

Within six months, however, the patient’s pain had significantly worsened. He couldn’t walk without assistance and, consequently, needed crutches. At this time, about a year after his transplant, he was referred to the rheumatology clinic.

In the clinic, the patient described intense, constant pain, primarily in both knees, but also affecting his legs. This was constant, disabling and present throughout the day, without a morning predilection. His past medical history was significant for hypothyroidism, hypertension and gastroesophageal reflux disease. He was on several medications, including cyclosporine for immunosuppression and acetaminophen, which he used as an analgesic.

The musculoskeletal exam was notable for bilateral quadriceps atrophy, crepitus in the knees and small, bilateral knee effusions. The rest of his physical examination proved unremarkable.

The initial laboratory workup revealed mild anemia (hemoglobin 11.4 g/dL), an elevated sedimentation rate (64 mm/hr) and an elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level (261 U/L). Because his other markers of liver function were normal, a bone-specific alkaline phosphatase was checked, which returned elevated (30 µg/L). The remainder of his labs were unremarkable.

The most effective treatment of CIPS is modification of the immunosuppressive regimen.

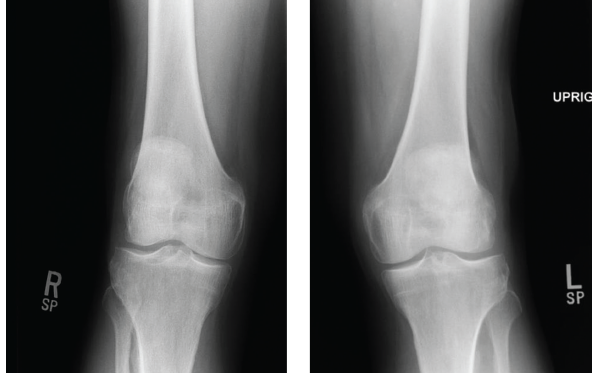

Further workup of this elevated bone-specific alkaline phosphatase included a bone scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of both knees (see Figure 3). The bone scan showed increased bilateral symmetric uptake in his knees and ankles (see Figure 4). An MRI of his knees revealed evidence of small effusions and mild bone marrow edema over the tibias, bilaterally.

Septic arthritis, myositis, osteomyelitis and inflammatory arthritis were considered; however, they were believed to be unlikely given the lack of typical clinical features. The normal neurological and vascular examination, absence of vasomotor instability, and trophic skin changes made complex regional pain syndrome less likely.

Figures 1 & 2: X-rays of the Right & Left Knees

Knee X-rays showed evidence of bilateral, medial joint space narrowing.

Because of the temporal relationship between the transplant and the onset of his complaints, iatrogenic causes were then investigated. The onset of his complaints correlated with when he was placed on cyclosporine. Additionally, the constellation of elevated, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, the abnormal bone scan and the MRI findings were all consistent with CIPS.

Subsequently, we attempted a trial of cyclosporine cessation and leg elevation. However, the patient did not tolerate alternate agents of immunosuppression for transplant, including mycophenolate mofetil, sirolimus and everolimus, due to a variety of side effects. The transplant team then restarted cyclosporine at a lower dose with close trough monitoring, and we added nifedipine and pregabalin to his regimen for pain control for CIPS.

Several months later, his symptoms impr-oved and he was able to walk comfortably.

Discussion

Figure 3: MRI of the Knee

The MRI revealed evidence of small effusions and mild bone marrow edema over the tibias, bilaterally.

Calcineurin inhibitor pain syndrome (CIPS) is an uncommon, debilitating side effect of calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) use. The most commonly implicated drugs are cyclosporine and tacrolimus.2 It has not yet been described in the literature with pimecrolimus. It may affect up to 20% of patients exposed to calcineurin inhibitors.3

CIPS was first described in the early 1990s as post-renal transplant distal limb bone pain, but was recognized as a distinct post-transplant pain syndrome in a 2001 paper by Grotz, et al.2,4,5 Typically, a temporal association exists between the initiation of calcineurin inhibitors and the onset of symptoms.

Because of the increased frequency of use of calcineurin inhibitors for post-transplant immunosuppression, CIPS has most frequently been chronicled in patients who undergo kidney, heart, lung, liver, pancreas or bone marrow transplantation. It has also been described in patients on CNIs for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis, Still’s disease, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.6-9

Patients usually present with symmetric, bilateral pain in the lower extremities, usually involving the knees, feet and the ankles. Physical examination is usually normal. An elevated bone-specific alkaline phosphatase may provide a useful laboratory clue.10 The typical radiological signs of CIPS include normal X-rays (or evidence of mild patchy osteoporosis), increased radiotracer uptake in the affected bones and joints on bone scintigraphy and patchy bone marrow edema visible on MRI.2,11

In some, but not all, studies, the severity of pain correlates with elevated CNI trough levels.2,10,12,13 However, most patients report symptomatic improvement with reduction in CNI levels.11

Figure 4: Bone Scan

The bone scan showed increased bilateral symmetric uptake in the patient’s knees and ankles.

The exact pathogenesis of CIPS is not clearly defined. However, CNIs cause increased vascular changes that disrupt bone perfusion and permeability. This leads to intraosseous vasoconstriction and bone marrow edema, which causes pain. It is also postulated that CNI use results in facilitation of pro-nociceptive processes by interrupting glial function and by inhibition of nuclear factor-activated T cells.14

Calcineurin regulates two-pore-domain potassium channels (K2Ps), which influence neuronal excitability and maintain resting membrane potentials, serving an important role in nociceptive regulation. The inhibition of calcineurin removes the regulation of these K2Ps, leading to enhanced neuronal excitability.14

The most effective treatment of CIPS is modification of the immunosuppressive regimen, either with the use of a non-calcineurin agent or with close monitoring of CNI levels and adjustment of the dose (as was done in this patient).2 Extremity elevation is also advised.2

Therapy adjuncts include calcium channel blockers, such as nifedipine; GABA analogs, such as pregabalin; and bisphosphonates, such as IV pamidronate.3,15 Controversy exists regarding the usefulness of adjunctive therapies, although improvement in patient-reported symptoms have been observed in several case reports and series. CIPS is usually completely reversible over a period of months, without long-term sequelae.

With a steady increase in the number of recipients of organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplants and, hence, more prevalent CNI use, this otherwise uncommon diagnosis is important to recognize. If identified early, cessation of CNIs in favor of an alternate immunosuppressive agent (or modification of the dose of CNI) is recommended, and musculoskeletal symptoms often quickly abate.

Priyanka Iyer, MD, MPH, is a second-year fellow in adult rheumatology at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to extend special thanks to Brittany Bettendorf, MD, who was an integral part of the treatment team and helped establish a unifying diagnosis.

References

- Adwan MH. An update on drug-induced arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2016 Aug;36(8):1089–1097.

- Grotz WH, Breitenfeldt MK, Braune SW, et al. Calcineurin-inhibitor induced pain syndrome (CIPS): A severe disabling complication after organ transplantation. Transpl Int. 2001;14(1):16–23.

- Elder GJ. From marrow oedema to osteonecrosis: Common paths in the development of post-transplant bone pain. Nephrology (Carlton). 2006 Dec;11(6):560–567.

- Lucas VP, Ponge TD, Plougastel-Lucas ML, et al. Musculoskeletal pain in renal-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 1991 Nov 14;325(20):1449–1450.

- Stevens JM, Hilson AJ, Sweny P. Post-renal transplant distal limb bone pain. An under-recognized complication of transplantation distinct from avascular necrosis of bone? Transplantation. 1995 Aug 15;60(3):305–307.

- Lawson CA, Fraser A, Veale DJ, Emery P. Cyclosporin treatment in psoriatic arthritis: A cause of severe leg pain. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003 May;62(5):489.

- Maeshima K, Ishii K, Horita M, et al. [Calcineurin-inhibitor induced pain syndrome (CIPS) in an adult-onset Still’s disease patient]. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 2008 Nov 10;97(11):2782–2784.

- Isaacs KL. Severe bone pain as an adverse effect of cyclosporin therapy for Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1998 May;4(2):95–97.

- Rahman AH, O’Brien C, Patchett SE. Leg bone pain syndrome in a patient with ulcerative colitis treated with cyclosporin. Ir J Med Sci. 2007 Jul–Sep;176(2):129–131.

- Tillmann FP, Jager M, Blondin D, et al. Post-transplant distal limb syndrome: Clinical diagnosis and long-term outcome in 37 renal transplant recipients. Transpl Int. 2008 Jun;21(6):547–553.

- Collini A, De Bartolomeis C, Barni R, et al. Calcineurin-inhibitor induced pain syndrome after organ transplantation. Kidney Int. 2006 Oct;70(7):1367–1370.

- Villaverde V, Cantalejo M, Balsa A, Mola EM. Leg bone pain syndrome in a kidney transplant patient treated with tacrolimus (FK506). Ann Rheum Dis. 1999 Oct;58(10):653–654.

- Bouteiller G, Lloveras JJ, Condouret J, et al. [Painful polyarticular syndrome probably induced by cyclosporin in three patients with a kidney transplant and one with a heart transplant]. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic. 1989 Nov;56(11):753–755.

- Smith HS. Calcineurin as a nociceptor modulator. Pain Physician. 2009 Jul–Aug;12(4):E309–E318.

- Gauthier VJ, Barbosa LM. Bone pain in transplant recipients responsive to calcium channel blockers. Ann Intern Med. 1994 Dec 1;121(11):863–865.