A typical patient with a rheumatic disease needs a multifaceted treatment approach to address comorbidities, minimize disability, promote quality of life and improve survival. To achieve these outcomes, rheumatology research has evolved from examining a single treatment to studying the best treatment approaches. Examples of these strategy trials include how to best combine pharmaceutical therapies, identifying which treatments are best used after traditional disease-modifying agents lose efficacy, studying the utility of non-pharmaceutical approaches for rheumatic diseases and identifying the optimal treatment target for disease management.1-10

The next generation of strategy trials will incorporate patient preferences, evaluate shared decision making and include societal/payer preferences for value-based decisions on specific interventions.11-15

Despite advances in research strategies, significant gaps in rheumatology care exist within our communities, particularly related to such patient-reported outcomes as pain.

Community-based rheumatology care has several challenges, including lack of resources to support treatment, lack of integrated, team-based models of care, long wait times to access a rheumatologist and a paucity of pain management strategies for most inflammatory rheumatic diseases.16

Given the expected increases in the prevalence of rheumatic diseases and associated costs to the patient and society, we propose a rheumatologist-led, team-based integrated model of care. This community-based approach can address gaps in care and mitigate future escalation of these costs.17-19

Benefits

Integrated care is an approach aimed at reducing inequalities of healthcare while improving quality of care and patient outcomes.

Icruci / shutterstock.com

Integrated care is an approach aimed at reducing inequalities of healthcare while improving quality of care and patient outcomes.20-22 Personalized, holistic approaches to chronic conditions (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, HIV/AIDS and chronic heart failure) in community settings have:

- Improved physical and psychological health;

- Empowered patients to self-manage their conditions;

- Increased adherence to treatment decisions; and

- Increased patient survival after a potentially life-threatening event.23-26

In January 2017, Steve Livshin, MD, my colleague and business partner—who also manages the pain clinic in close proximity to our center—and I set out to develop and lead a community-based integrated model of care in North York, Ontario, Canada, to determine: 1) its viability, 2) the ability of this model to reduce care gaps in early diagnosis and management, and 3) the impact of shared decision making on patient-reported outcomes.

The patient is an important element of this model, and shared decision making is at its center. How a patient and provider arrive at treatment choices and prioritize shared targets is of utmost importance. In this model, the patient and the provider team each have an equal voice in an informed dialogue about how to approach patient care and address patient needs. This approach necessitates holistic care, coupled with a patient empowered to participate in their own treatment decisions with their rheumatologist through education and decision support tools.

It also forces a deeper examination of how to treat musculoskeletal pain, which is a dominant symptom among our patients. This is particularly important, because disease-modifying therapies often provide only part of the solution.

The First Knot: Select the Site

Prior to opening the Center of Integrated Care, members of my team and I engaged with various stakeholders to solicit their views and experiences: These stakeholders included primary care physicians, community rheumatologists, researchers (in particular, members of the Outcomes Measures in Rheumatology special interest group of shared decision making), hospital representatives and patient support groups, such as the Arthritis Society, Osteoporosis Society and the Canadian Rare Disease Organization.

I made plans to transition my practice from a downtown teaching hospital to a non-medical building complex close to a pain center to ensure my patients could have timely access to pain treatments beyond my scope of practice. The complex allowed for street level access to my clinic for those with disabilities, as well as ample free parking.

My new catchment area serves 1.9 million people, many of whom have a high level of chronic disease. Despite this, this population is served by relatively few specialists. This area includes an indigenous community; 47% of its residents are minorities, and 12.5% of the people are older than 65.27

The dichotomy of the demographic profile in this area has grown: on one side are families supported by single providers, which have the lowest incomes; on the other side are some of the richest neighborhoods in the greater Toronto area.

During the center’s development, I took a drive with a local real estate agent to learn about the living patterns of potential patients: where they might work, where they might live, where they would shop for groceries, what restaurants they might frequent and what recreational facilities were available to them (e.g., ice rinks and baseball facilities). If this model were to be fully integrated, it would be necessary to reduce the gaps in rheumatic disease care often caused by socioeconomic factors and other barriers to care.

High-quality integrated care is a model in which a holistic consideration passes through an evidence-based filter & is narrowed to practical options presented to the empowered patient for shared decision making.

The Second Knot: Establish Holistic Care

Our patients are more than just patients, and medicine includes everything from the food we eat to the love we receive, the availability and suitability of shelter, the strength of our relationships, our emotional health and our sense of self. Our approach to care must be holistic and take the entire person and patient experience into consideration.

I was unaware of what holistic truly meant until I read further on the subject. I can tell you there is nothing touchy-feely about this strategy: It is not a throwback to the hippie era, nor is it a way to generate revenue by incorporating wellness fads into your practice. These fads have destroyed the essence of what holistic care means. Being holistic does not mean exploring only non-pharmaceutical interventions.

When I speak of being holistic with regard to treating rheumatic diseases, it is a commitment to systematically address the physical (disease-specific), socioeconomic and local healthcare realities to achieve disease-specific and patient-centered care goals. For this approach to succeed, the following are essential:

- A deep understanding of the patient’s mental and socioeconomic state of being when they are being assessed;

- Consideration of their health state (e.g., flares) between assessments;

- An outline of their probability for a specific disease trajectory (prognosis and likelihood for disease progression, as appropriate); and

- A grasp of the practical aspects (e.g., support structures; level of physical, mental and financial independence; limiting beliefs; level of support from payers, healthcare providers and/or others involved in the care plan) required to create a suitable plan of action to achieve the shared outcomes sought.

Holistic care couples health promotion and prevention of future events with disease management.

High-quality integrated care is a model in which a holistic consideration passes through an evidence-based filter and is narrowed to practical options presented to the empowered patient for shared decision making. The paradigm to follow includes a consideration of the patient’s values and preferences.28

The Third Knot: The Team to Execute Holistic Care

Patients come to the new practice from all over the area, many drawn by the concept of integrated care for rheumatic disease and pain management.

I was able to assemble a team that includes educators (for pharmaceutic therapies, osteoporosis/supplement management and exercise), nurses, a chiropractor, an educator from the Arthritis Society, a dietician, patient advocate/peer support and a group of like-minded physicians, including primary care physicians with a focus in musculoskeletal disorders.

The determination of how to provide care in a team context is as important as the specific care to provide. Our team shared ideas through on-site educational programs and shared thoughts at the bedside of the patient in challenging cases where there was chronic, widespread, musculoskeletal pain.

1 Year Later: A Care Revolution

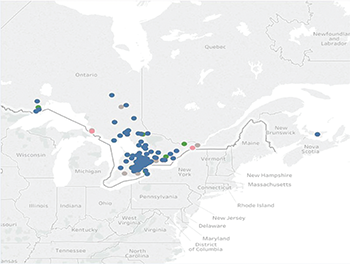

In a 12-month period, 971 patients have been seen at our site with more than one follow-up visit. Of those, 47% have inflammatory arthritis or osteoarthritis, 17% have connective tissue disease, and 36% have fibromyalgia. Surprisingly, many of our patients came from communities outside of North York (see map, above), including Thunder Bay, North Bay and Prince Edward Island.

Notably, some patients looking specifically for integrated care for rheumatic disorders and pain management found us through word of mouth. This suggests this model could lend itself to other communities. In the next phase of our model, we will be providing telemedicine services to reach these communities more effectively.

After one year, we found:

- An increase in patient empowerment (e.g., patients knew when to come into the clinic for a flare, when to get vaccinations, when to stop therapies to prevent new or worsening infections, when to access other specialists and how to self-manage, including pain management strategies);

- An increase in collaborative care; and

- An increase in early diagnosis of rheumatic diseases, in part by creating an accelerated pathway to complete the necessary diagnostic evaluation. We were able to achieve this by having a laboratory on site that could test for rare diseases (e.g., Pompe disease) and piloting innovative bedside techniques for earlier diagnosis, such as handheld ultrasound devices for synovitis.

These advances may appear simple, but they definitely are not simplistic. We pushed the boundaries of our understanding of rheumatic diseases every day, and this allowed for a revolution in care. It allowed patients to return to functional capacity in their communities sooner by reducing the time it took them to access care and the need for frequent clinical visits, and by providing them with self-management skills and options.

Patients are often frustrated when attempting to describe pain. For example, a patient from another country or another culture may have an exasperating experience when attempting to describe symptoms to a new care provider. When we make that patient an equal member of a transdisciplinary team, however, that patient can be an integral part of shared decision making. Educate that patient about the underlying symptomology of their condition, and they become empowered to select their care and desired outcomes. The patient can make choices that can incrementally help them over time and can be followed by the team for ongoing assessment of the success of the strategic approach.

When a patient is educated about the source of pain and functional limitations, they can be their own best advocate for the best way to navigate a complicated care system. This allows for an earlier and more accurate diagnosis, and for a more targeted continuation of care.

In an integrated model, coordination can occur, and the patient can more easily determine who is an appropriate care provider for a particular aspect of their disease. This results in decreased costs, stress, time and personal resources, while creating efficient delivery of care.

Now that I have transitioned from an academic practice model to an integrated care model, when I turn out the lights as I leave the center to go home, I know that I have not set limits on my patients’ potential for improvement. With their input, we have unraveled a Gordian knot, which I believe will lead them to a better destiny and a more enriched life.

Shikha Mittoo, MD, MHS, FRCPC, is the medical director and co-founder of Involved Medicine, medical advisor for InfuseRX, a staff rheumatologist at University Health Network and an adjunct assistant professor at the University of Toronto, Canada. Dr. Mittoo is a rheumatologist with an interest in inflammatory arthritis and lung disease.

Shikha Mittoo, MD, MHS, FRCPC, is the medical director and co-founder of Involved Medicine, medical advisor for InfuseRX, a staff rheumatologist at University Health Network and an adjunct assistant professor at the University of Toronto, Canada. Dr. Mittoo is a rheumatologist with an interest in inflammatory arthritis and lung disease.

References

- Brinkman GH, Norvang V, Noril ES, et al. Treat to target strategy in early rheumatoid arthritis versus routine care—A comparative clinical practice study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018 Jul 25. pii: S0049-0172(18)30184-7.

- Vermeet M, Kuper HH, Bernelot Moens HJ, et al. Adherence to treat-to-target strategy in early rheumatoid arthritis: Results of the DREAM remission induction cohort. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012 Nov 23;14(6):R254.

- Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): A randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Nov;52(11):3381–3390.

- Primdahl J, Sørensen J, Horn HC, et al. Shared care or nursing consultations as an alternative to rheumatologist follow-up for rheumatoid arthritis outpatients with low disease activity—patient outcomes from a 2-year, randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Feb; 73(2):357–364.

- Chung YL, Alexanderson H, Pipitone N, et al. Creatine supplements in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies who are clinically weak after conventional pharmacologic treatment: Six-month, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 May 15;57(4):694–702.

- Fogarty FA, Booth RJ, Gamble GD, et al. The effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction on disease activity in people with rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Feb;74(2):472–474.

- Szczurko O, Cooley K, Millis EJ, et al. Naturopathic treatment of rotator cuff tendinitis among Canadian postal workers: A randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Aug 15;61(8):1037–1045.

- Häuser W, Bernardy K, Arnold B, et al. Efficacy of multicomponent treatment in fibromyalgia syndrome: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Feb 15;61(2):216–224.

- O’Dell JR, Mikuls TR, Taylor TH, et al. Therapies for active rheumatoid arthritis after methotrexate failure. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jul 25;369(4):307–318.

- Sephton SE, Salmon P, Weissbecker I, et al. Mindfulness meditation alleviates depressive symptoms in women with fibromyalgia: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Feb 15;57(1):77–85.

- Fayad F, Ziade NR, Merheb G, et al. Patient preferences for rheumatoid arthritis treatments: Results from the national cross-sectional LERACS study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018 Aug 31;12:1619–1625. eCollection 2018.

- Toupin-April K, Barton J, Fraenkel L, et al. Toward the development of a core set of outcome domains to assess shared decision-making interventions in rheumatology: Results from an OMERACT Delphi Survey and Consensus Meeting. J Rheumatol. 2017 Oct;44(10):1544–1550.

- Park W, Hrycaj P, Jeka S, et al. A randomised, double-blind, multicentre, parallel-group, prospective study comparing the pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of CT-P13 and innovator infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: The PLANETAS study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Oct;72(10):1605–1612.

- Jørgensen KK, Olsen IC, Goll GL, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (NOR-SWITCH): A 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017 Jun 10;389(10086);2304–2316.

- Hazlewood GS, Bombardier C, Tomlinson G, et al. Treatment preferences of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: A discrete-choice experiment. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016 Nov;55(11)1959–1968.

- Widdifield J, Paterson JM, Bernatsky S, et al. Access to rheumatologists among patients with newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis in a Canadian universal public healthcare system. BMJ Open. 2014 Jan 31;4(1):e003888.

- Widdifield J, Paterson JM, Bernatsky S, et al. The rising burden of rheumatoid arthritis surpasses rheumatology supply in Ontario. Can J Public Health. 2013 Oct 31;104(7):e450–e455.

- Arthritis Alliance of Canada.

- Health fact sheets: Chronic conditions, 2015. Arthritis. Symbol of Statistics Canada.

- Curran M. Integrated care is a fundamental design feature that will strengthen healthcare around the world. International Foundation for Integrated Care. 2017 May 25.

- Service delivery and safety: WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services. Interim report. World Health Organization. 2015.

- Service delivery and safety: Framework on integrated people-centred health services. World Health Organization. 2016 May.

- MacInnes J, Williams L. A review of integrated heart failure care. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2018 Jun;1–8.

- Koolen EH, van der Wees PJ, Westert GP, et al. The COPDnet integrated care model. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018 Jul 19;13:2225–2235.

- Sterling S, Chi F, Weisner C, et al. Association of behavioral health factors and social determinants of health with high and persistently high healthcare costs. Prev Med Rep. 2018 Jun 27;11:154–159.

- Baxter S, Johnson M, Chambers D, et al. Understanding new models of integrated care in developed countries: A systematic review. NIHR Journals Library. 2018 Aug.

- Central LHIN (Local Health Integration Network).

- Guyatt GH, Haynes RB, Jaeschke RZ, et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature. JAMA. 2000;284(10):1290–1296.