Since it was first reported in 1916, a correlation between inflammatory myopathies and cancer has been noted in several studies. Population studies have confirmed this relationship, and the phrase cancer-associated myopathy has entered the vernacular. Over the past decade, research efforts have shifted toward revealing associations between autoantibodies and clinical phenotypes. One subset of auto-antigens targeting p155/140 have been implicated in oncogenesis and may play a role in screening cancer patients for inflammatory myositis.

The Patient

At our rheumatology clinic, an 81-year-old woman with a past medical history of an undifferentiated neuroendocrine carcinoid tumor involving the ovaries and bowel presented for evaluation of a skin rash concerning for dermatomyositis.

The patient’s malignancy had initially manifested as a bowel obstruction, with metastasis to the mesenteric lymph nodes. Eighteen months prior to the visit, she underwent a bilateral oophorectomy. She subsequently began to develop a pruritic rash over her chest, which eventually covered her back, arms, stomach and legs (see Figures 1, 2 and 3, right and opposite).

The rash initially improved with the application of topical triamcinolone cream. Subsequently, she began to experience myalgias in her shoulders, legs and proximal arms. This pain was accompanied by the appearance of periorbital edema. She was eventually sent to a dermatologist for further evaluation.

Clinically, the dermatologist noted a heliotrope eruption, Gottron’s papules, a shawl sign and a V sign. A skin biopsy was consistent with dermatomyositis. She began treatment with prednisone and methotrexate, and was referred to our office for further management.

Although it’s generally accepted dermatomyositis patients should be screened for cancer, no consensus exists as to what screening should entail.

The patient’s laboratory tests did not demonstrate an antinuclear antibody, anti-double stranded DNA antibody or rheumatoid factor. Muscle enzymes, including creatine kinase and aldolase, were within normal limits, although mild proximal muscle weakness existed on examination. Noteably, her chromogranin A was elevated at 70 nmol/L (upper limit of normal [ULN]: 15 nmol/L), and her 24-hour urine 5-HIAA was 9.2 mg/24h (ULN 5.99 mg/24h).

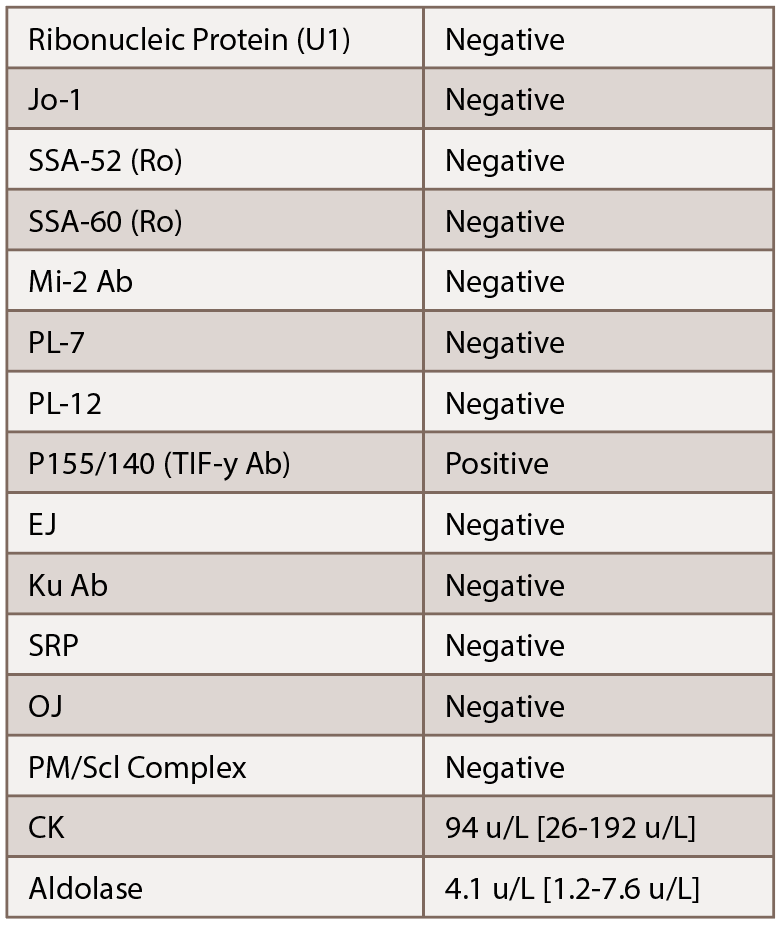

Due to the persistent rash, the patient’s methotrexate dose was increased from 15 to 20 mg weekly. She was also instructed to remain on prednisone. Initial labs, including a myositis antibody panel, demonstrated the following:

Given the elevated p155/140 antibody, we were concerned about a cancer-associated dermatomyositis. Additionally, given her lack of significant muscle involvement with normal enzymes, we suspected an amyopathic variant. With her history of an undifferentiated neuroendocrine tumor, recommendations were made for her to follow up with her oncologist for further evaluation. Subsequent lab tests demonstrated her chromogranin A increased to 82 nmol/L.

Despite immunosuppression, the patient’s rash persisted. Hydroxychloroquine was added as a steroid-sparing agent for her skin manifestations, and eventually, mycophenolate mofetil was added as well. The patient’s oncologist placed her on octreotide therapy to treat her carcinoid tumor. With the addition of octreotide, her rash resolved. However, her symptoms returned when the therapy was stopped.

The rash recurred mainly on the patient’s upper chest. It was initially intermittent, but gradually became persistent and was associated with flushing and pruritis. Her heliotrope eruptions and Gottron’s papules ultimately resolved. At follow-up visits, it was determined her recurrent rash was due to carcinoid rather than her dermatomyosits.