Most Sunday mornings, I make myself an exceptional cup of pour-over coffee and sit down on my deck with the latest issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. I check out the image of the week. I read the case report with pen in hand, racing to diagnose the patient before the authors spill the beans. And for extra credit, I glance at the original articles, hopeful for breaking news in the world of rheumatology.

Most Sunday mornings, I make myself an exceptional cup of pour-over coffee and sit down on my deck with the latest issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. I check out the image of the week. I read the case report with pen in hand, racing to diagnose the patient before the authors spill the beans. And for extra credit, I glance at the original articles, hopeful for breaking news in the world of rheumatology.

It doesn’t happen often. But every now and then, I come across an article that makes me spit out my fancy coffee. I don’t mind making another cup when that occurs.

In the Feb. 22 issue of the journal, Müller et al. published a case series with follow-up describing 15 patients with severe autoimmune rheumatic diseases (ARDs) treated with a single infusion of CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells. The therapy appeared to be “feasible, safe and efficacious in all patients.”1

To be specific, all patients achieved a significant decrease in disease activity scores and/or remission, and immunosuppressive therapy was completely stopped in all patients after a median follow-up of 15 months.

I repeat. Immunosuppressive therapy was completely stopped in all patients after a median follow-up of 15 months.

Do I have your attention? Excellent. I thought so.

In this article, we touch on high points of this trial and chat with expert oncologist Matthew J. Frigault, MD, clinical director, Cellular Therapy Service, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), and assistant professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, for his take on the ins and outs, and future of CAR-T cell therapy (cell therapy).

Background

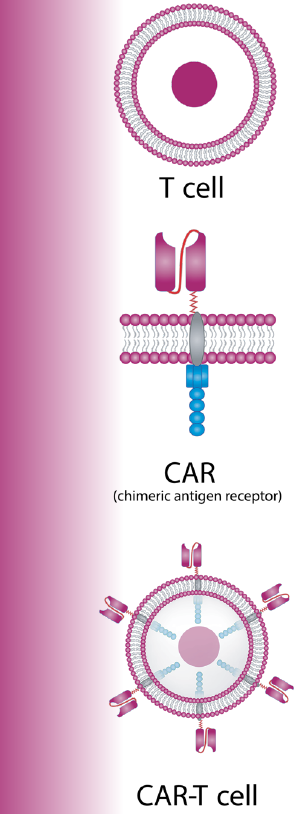

CAR-T cells, a type of cell therapy, have become a powerful option in the oncologist’s toolbox. A patient’s own T cells are collected from the body and re-engineered in the lab to produce new surface proteins called CARs. Then, they’re infused back into the patient, where the CARs bind to the target cells—in this case B cells that express CD19—and kill them.2

Six CAR-T cell therapies (e.g., tisgenlecleucel) have been approved by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration for the treatment of certain relapsed or refractory hematologic neoplasms. The question is: If targeting malignant B cells has improved the treatment of cancers, would targeting autoreactive B cells show similar results in ARDs? One can dream.

Currently, targeting autoreactive B cells in ARDs is limited to monoclonal antibodies that deplete or inhibit their activation (e.g., rituximab, belimumab). Such therapies have certainly made a difference, but they haven’t resulted in long-lasting drug-free remission. CAR-T cells, on the other hand, have the potential to deplete B cells deeper by targeting CD19, a surface molecule expressed by many B cells and plasmablasts. Results from Müller et al.’s case series speak to this potential.