Most Sunday mornings, I make myself an exceptional cup of pour-over coffee and sit down on my deck with the latest issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. I check out the image of the week. I read the case report with pen in hand, racing to diagnose the patient before the authors spill the beans. And for extra credit, I glance at the original articles, hopeful for breaking news in the world of rheumatology.

Most Sunday mornings, I make myself an exceptional cup of pour-over coffee and sit down on my deck with the latest issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. I check out the image of the week. I read the case report with pen in hand, racing to diagnose the patient before the authors spill the beans. And for extra credit, I glance at the original articles, hopeful for breaking news in the world of rheumatology.

It doesn’t happen often. But every now and then, I come across an article that makes me spit out my fancy coffee. I don’t mind making another cup when that occurs.

In the Feb. 22 issue of the journal, Müller et al. published a case series with follow-up describing 15 patients with severe autoimmune rheumatic diseases (ARDs) treated with a single infusion of CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells. The therapy appeared to be “feasible, safe and efficacious in all patients.”1

To be specific, all patients achieved a significant decrease in disease activity scores and/or remission, and immunosuppressive therapy was completely stopped in all patients after a median follow-up of 15 months.

I repeat. Immunosuppressive therapy was completely stopped in all patients after a median follow-up of 15 months.

Do I have your attention? Excellent. I thought so.

In this article, we touch on high points of this trial and chat with expert oncologist Matthew J. Frigault, MD, clinical director, Cellular Therapy Service, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), and assistant professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, for his take on the ins and outs, and future of CAR-T cell therapy (cell therapy).

Background

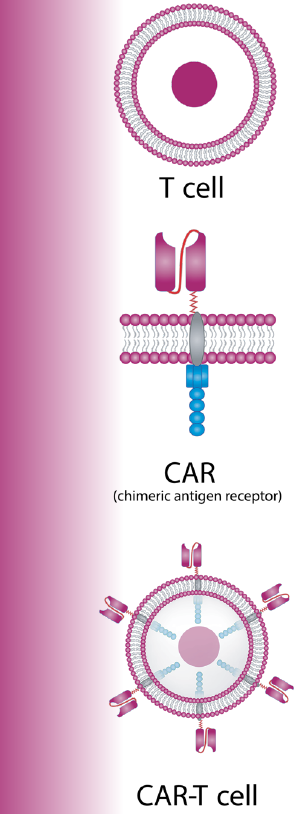

CAR-T cells, a type of cell therapy, have become a powerful option in the oncologist’s toolbox. A patient’s own T cells are collected from the body and re-engineered in the lab to produce new surface proteins called CARs. Then, they’re infused back into the patient, where the CARs bind to the target cells—in this case B cells that express CD19—and kill them.2

Six CAR-T cell therapies (e.g., tisgenlecleucel) have been approved by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration for the treatment of certain relapsed or refractory hematologic neoplasms. The question is: If targeting malignant B cells has improved the treatment of cancers, would targeting autoreactive B cells show similar results in ARDs? One can dream.

Currently, targeting autoreactive B cells in ARDs is limited to monoclonal antibodies that deplete or inhibit their activation (e.g., rituximab, belimumab). Such therapies have certainly made a difference, but they haven’t resulted in long-lasting drug-free remission. CAR-T cells, on the other hand, have the potential to deplete B cells deeper by targeting CD19, a surface molecule expressed by many B cells and plasmablasts. Results from Müller et al.’s case series speak to this potential.

A Trial Worth Reading

Müller et al. evaluated 15 patients with severe, refractory systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE, n=8), idiopathic inflammatory myositis (IIM, n=3) and diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis (SSc, n=4).1 All patients had previously had an inadequate response to at least two prior immunosuppressants (median, 5; range, 2–14 prior treatments). All SLE patients had active skin and renal disease (biopsy-confirmed Class III/IV lupus nephritis). All IIM patients had active lung and muscle disease. All SSc patients had active lung and skin disease. Six patients were men and nine were women. Patient ages ranged from 20–60 years. Disease duration ranged from one to 20 years.

Each patient received a single infusion of CD19 CAR-T cells after preconditioning with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide. Every single patient achieved a significant decrease in disease activity scores and/or remission, and all patients successfully stopped glucocorticoids and all other immunosuppressive medications as of the final follow-up visit (median 15 months; interquartile range 7–19 months).

More specifically, all eight SLE patients met Lupus Low Disease Activity State (LLDAS) criteria and had Definition of Remission in SLE (DORIS) remission after six months. SLE Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) scores were zero, and British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG) status at follow-up showed resolution of SLE in all major disease categories after six months. Up to 29 months out, SLE disease activity remained absent in all patients. Anti-dsDNA antibodies disappeared and remained negative, complement factor C3 levels normalized, and proteinuria resolved during the entire observation period.

All three IIM patients had an ACREULAR Total Improvement Score major clinical response, normalization of creatine kinase (CK) levels and muscular function after three months, and improvement of extramuscular disease activity.

All four patients with SSc saw decreases in the European Scleroderma Trials and Research Group (EUSTAR) activity index (median change –4.2 points, interquartile range –4.7 to –2.3), as well as a decrease in modified Rodnan skin scores (median change –9, interquartile range –17 to –7).

Adverse effects of CAR-T cell therapy were minimal and tolerable. No patients died. No moderate- or high-grade cytokine release syndrome or immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) occurred. There were no prolonged bone marrow toxic effects. Mild infections occurred, with only one patient requiring hospital admission (for a diagnosis of pneumonia, which resolved with antibiotics). New-onset hypogammaglobulinemia was uncommon.

Interview with an Expert

Dr. Frigault

Dr. Frigault was kind enough to sit down and let me pick his brain about the ins and outs, as well as the future, of cell therapy in rheumatic disease.

How did you become involved with cell therapy?

Dr. Frigault (MF): I started working with cell therapy back in medical school. I fell in love with the concept of a Frankenstein immune system that could do good. I continued this work throughout residency, fellowship and my postdoctoral training. I was ultimately hired to grow a cell therapy program here at MGH as all this was starting to emerge. The program has grown bigger every year. We’ve added all different types of patients.

How are you working with rheumatologists?

MF: Oncology took a lot from rheumatology (e.g., checkpoint inhibitors), and now it’s going in the reverse direction. Cell therapy is complicated from a regulatory and infrastructure standpoint. So when I saw the use of cell therapy in ARDs coming, I made a pitch to start doing cell therapy studies in collaboration with non-oncology primary investigators. Oncology is in a really good position to run multiple, highly complex studies with lots of patients. We are used to doing that. So if we can bring efficiencies to rheumatologists interested in running cell therapy trials too, I’m on board. I want to get them excited and invested, and I want to provide the support safety net they need to do this work. I’ve tried to make it like pushing an easy button.

Are you running any cell therapy trials in patients with autoimmune disease right now?

MF: Yes. We are currently running cell therapy trials for SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, myasthenia gravis and pan-autoimmune conditions.

What kind of patients are good candidates for cell therapy? Are there any frank contraindications?

MF: The only real contraindication is renal failure (CrCl <30 mL/min), and even that is somewhat relative. This is due to the need to use fludarabine for lymphodepletion, and it’s renally cleared with the potential risk of neurotoxicity. Relative contraindications include active infections and chronic long-term steroid use (due to negative effects on the immune system). We try to get the steroid dose down as low as possible for a period of time because there’s some thought that they might impact overall efficacy from a cancer standpoint. Otherwise, patient optimization is key.

Can you walk us through the patient’s experience from start to finish? What’s involved in the process?

MF: The patient has a consult to fully understand the risks and benefits. There’s a teaching session with a nurse. A social worker speaks with the patient and their family to identify areas of need. Then, we file the paperwork for insurance approval. Once approved, some CAR-T cell therapies require the patient to stay within the area for a set amount of time. Accordingly, some insurance companies have also started to offer housing support for patients meeting certain criteria.

Procedure-wise, we collect the patient’s T cells via apheresis, which takes about six hours. Then we wait 14–28 days for the product to transform them into CAR-T cells. During this time, the patient [receives] three days of chemotherapy for preconditioning [lymphodepletion] and two days of rest, and then the CAR-T cells are reinfused. We’re even doing this as an outpatient procedure for some, which is allowing us to treat more patients.

Why is lymphodepletion with chemotherapy necessary?

MF: Lymphodepletion is needed to allow for CAR-T cell expansion. The point is to create immunologic space. We just built the patient a Ferrari. But if they’re in rush hour, it doesn’t matter if they’re driving a Pinto or a Ferrari—they aren’t going anywhere. Lymphodepletion opens up the highway so the brand-new Ferrari can take off and go.

What about complications?

MF: The number one cause of non-relapse mortality in most patients is infection. That’s because oncology and rheumatology patients don’t have normal functional immune systems to begin with. Early infections are largely bacterial, with later infections driven by viral pathogens. So in the first 30 days, we’re trying to mitigate risk, maintain appropriate blood counts and monitor for cytokine release syndrome and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome.

Do rheumatology patients behave differently than oncology patients after receiving CAR-T cells?

MF: Interestingly, in patients with ARDs, we don’t see the same degree of prolonged B cell aplasia. Their B cells have the potential to reconstitute, but as a much more naive B cell population that doesn’t have as much autoreactivity.

How far off do you think we are from CAR-T cell therapy being available to patients with ARDs?

MF: Three to four years.

What are the limitations of implementing CAR-T cell therapy on a larger scale for patients with ARDs?

MF: It’s cumbersome to manufacture the individual products, and capacity to make enough would be a challenge. Cost is also an issue, with the product being about $500,000, and if you add the hospital stay about $1 million.

Do you think there could be a day when CAR-T cell therapy becomes standard of care as curative therapy for ARDs?

MF: As we make cell therapy safer and better understand what we’re doing, it could be. It really comes down to risks and benefits. We started cell therapy trials in end-stage oncology patients with relapsed/refractory disease. Now, we are using it in second-line patients, and current trials are looking at it as first-line therapy. I think there are certain high-risk patients with ARDs where it could make sense as first-line. We are working on therapies to prevent side effects and complications. If we can develop the right strategy and decrease the likelihood of toxicity, it could open the door for more patients.

What needs to happen next?

MF: We need more excitement from rheumatologists. I’d love for rheumatology to really dive into cell therapy and collaborate with us. I understand that there’s some degree of hesitancy since it’s an unknown, but this is an area rife with opportunity for those early in their careers, and it’s a huge area of need that needs to be addressed. I see an opportunity for partnerships.

Conclusion

In summary, CD19 CAR-T cell therapy holds promise for patients with severe ARDs, and more controlled clinical studies are needed. Sustained disease and drug-free remission may be closer than we think.

Samantha C. Shapiro, MD, is the executive editor of Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. As a clinician educator, she practices telerheumatology and writes for both medical and lay audiences.

Samantha C. Shapiro, MD, is the executive editor of Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. As a clinician educator, she practices telerheumatology and writes for both medical and lay audiences.

References

- Müller F, Taubmann J, Bucci L, et al. CD19 CAR T-cell therapy in autoimmune disease – A case series with follow-up. N Engl J Med. 2024 Feb;390(8):687–700.

- June CH, Sadelain M. Chimeric antigen receptor therapy. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 5;379(1):64–73.

- How CAR T-cell therapy works. Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Accessed 2024 June 5. https://www.dana-farber.org/cancer-care/treatment/cellular-therapies/car-t-cell-therapy/how-car-t-cell-therapy-works.