Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) was first described in the British Medical Journal in 1897 by Scottish otolaryngologist Peter McBride.1 GPA is a relatively rare, systemic necrotizing vasculitis that can make diagnosis challenging. The incidence has been estimated anywhere between two and 12 cases per million.2 GPA mainly affects adults between the ages of 45 and 60. Most commonly, the upper and lower airways (90%), the kidneys (80% in the first two years of disease) and the skin are involved, but patients can have a multitude of other symptoms.3

In this case presentation, we aim to increase awareness, as well as discuss developments in our understanding of the role of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) and their importance in the clinical monitoring and treatment of GPA.

Case Presentation

A 44-year-old Caucasian male with a five-year history of severe headaches, cough, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, tinnitus, hearing loss, changes in his voice and sinus congestion was evaluated and treated multiple times with intranasal oxymazoline, various antibiotic regimens and systemic steroids. Due to only partial relief and recurrent upper respiratory symptoms, an ear, nose and throat (ENT) consultation was obtained.

The initial ENT evaluation revealed narrowing of the nasal vestibules, boggy and enlarged nasal turbinates with a normal orocavity and oropharynx. During the waxing and waning course of his symptoms, he also reported multiple episodes of epistaxis and purulent nasal secretions that, at times, he described as “tissue coming out from his nose.” When he was receiving treatment with antibiotics and steroids, his symptoms would briefly improve. Then, shortly after discontinuing treatment, his symptoms would recur.

The patient was referred to an allergy/immunology specialist, who started him on subcutaneous immunotherapy. The patient reported minimal, if any, improvement. He continued to experience debilitating symptoms.

He was then referred to an infectious disease specialist. Upon evaluation, no signs of active or remote infectious process were discovered as a source of his symptoms. Prior to the rheumatology evaluation, the patient noted a few emergency department visits in the previous 12 months for intense, throbbing headaches, epistaxis and an extensive rash over his chest, worsening of his hearing and voice changes during the day. He required myringotomy and aspiration of his right ear. After many visits to the ENT office, the patient was referred to rheumatology for further evaluation.

A comprehensive review of systems revealed that at least for the previous 12 months, the patient had experienced fevers, chills, night sweats, extreme fatigue, lack of appetite, unintentional weight loss of 15 lbs., dyspnea on exertion, arthralgias, myalgias, heartburn, hiccups and frequent eructation. Occasionally, he would note swelling of his knees and ankles. The past two months, he had flu-like symptoms accompanied by severe headaches. He had two episodes of extensive purpuric rashes on his torso. He continued to complain about tinnitus, hoarseness and changes in his voice, especially toward the end of the day.

Several studies have shown that rituximab may be superior to cyclophosphamide in achieving clinical remission at six & 12 months after initiating induction therapy. Rituximab has also been shown to be superior to cyclophosphamide to achieve immunosuppression in patients with PR3-positive ANCA-vasculitis.

The patient made the remark that “only prednisone helps me.” He denied wrist or foot drop, dry mouth or eyes, malar rash, oral and nose ulcerations, alopecia or hair thinning, abdominal pain, blood in the urine or in the stool, and frothy urine.

Based on his presentation, an autoimmune and vasculitis work-up was initiated. Markers of inflammation were elevated (ESR 40.8 mm/hr, upper limited of normal (ULN)< 10mm/hr, CRP 43, ULN <10mg/L), the ANA and subset serology (including dsDNA, SSA/SSB, RNP, Sm) were negative. Complement levels were normal. Urinalysis was normal with no signs of proteinuria, hematuria or casts. ANCA antibodies came back positive (titer 1:230, Ref < 1.20 AI), with a positive PR3 antibody (titer 5.3, ULN <1.0 AI) and negative MPO-ANCA. Serology for hepatitis B and C and tuberculosis was negative.

A review of the prior emergency department evaluation for his severe headaches revealed a computed tomography (CT) scan of his head that was positive for severe maxillary sinusitis, no acute intracranial hemorrhages/ischemia. A CT of his sinuses confirmed the involvement of the maxillary sinuses bilaterally, but no air fluid levels were noted. The frontal and ethmoidal sinuses were clear, and the ostiomeatal units were unremarkable.

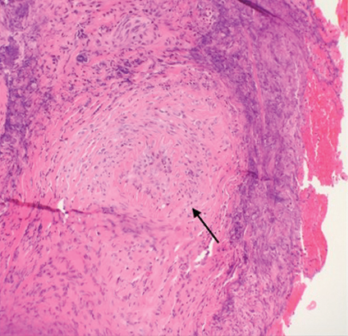

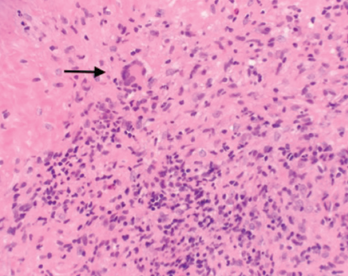

After rheumatology evaluation, treatment with high-dose oral steroids (prednisone 1 mg/kg daily) was initiated and patient was referred back to ENT for sinus biopsy. The pathology report was consistent with granulomatous vasculitis and necrosis involving sinonasal mucosa, revealing extensively inflamed and ulcerated sinonasal tissue with dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and granulation tissue formation. Occasional profiles of medium-size arterioles show infiltration by lymphocytes and occasional giant cells (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. A nasal biopsy shows intimal infiltration of the small blood vessels (black arrow).

To evaluate disease extension, a CT of the chest was obtained. No hilar or mediastinal adenopathy, lung nodules or pleurisy were noted. An audiogram was also performed and was negative for hearing loss.

Based on these data, the disease was considered limited to upper airways. In addition to glucocorticoids, we initiated therapy with oral methotrexate. Clinically, the patient improved quickly. Constitutional symptoms completely resolved, as did the nasal congestion. His ear pain decreased, and his voice improved, along with his appetite and fatigue. Methotrexate was gradually increased over the course of the next three months from 10 mg to 20 mg weekly. The dose of prednisone was gradually tapered over the course of eight months. The patient was also prophylactically treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (3x/week), weekly alendronate, daily calcium and vitamin D supplementation.

Three months after GPA diagnosis, his labs noted new-onset microscopic hematuria. A nephrology evaluation was obtained. A kidney biopsy was obtained, and fortunately it was negative for vasculitis changes. Shortly after, the patient was noted to have microscopic kidney stones.

Over the course of the next year, the patient has experienced complete resolution of virtually all of his symptoms, has been successfully tapered off of prednisone without any recurrence of symptoms and is tolerating methotrexate without any major adverse reactions. He continues to follow up with rheumatology regularly.

Discussion

Figure 2. A nasal biopsy shows giant multinuclear cells (black arrow).

GPA is a complex, multisystem disease that is often difficult to diagnose, especially at the initial presentation. Early diagnosis is critical to halt the disease process and progression. Patients with GPA diagnosed early in the disease process, especially in the ambulatory setting, have had favorable outcomes compared with patients enrolled in randomized controlled trials who are usually referred to tertiary centers and present with advanced disease.4 This can certainly be attributed to the delay in diagnosis and or misinterpretation of initial presenting symptoms.

Without increased awareness and proper training to recognize this disease, physicians often omit a vasculitis diagnosis from their differentials. Reported symptoms include, but are not limited to, fatigue, fever, weight loss, arthralgias, rhinosinusitis, cough, voice changes, hearing loss, dyspnea and skin rashes.

Although our patient had a strikingly similar presentation, he was officially diagnosed with GPA eight years after the onset of symptoms. During the five years between the worsening of his symptoms and the diagnosis of GPA, we have been able to track multiple medical visits. Our patient had visited his primary care physician, ENT and infectious disease specialists, as well as made multiple emergency department visits due to recurrent, debilitating symptoms.

A delay in diagnosis can often be fatal. Therefore, establishing a diagnosis early in the disease process is crucial. In 1990, the ACR established criteria to help distinguish GPA from other forms of vasculitis.5 The following criteria were proposed and studied: nasal or oral inflammation (painful or painless oral ulcers, or purulent or bloody nasal discharge), abnormal chest radiograph showing nodules, fixed infiltrates or cavities, abnormal urinary sediment (microscopic hematuria with or without red cell casts) and granulomatous inflammation on biopsy of an artery or perivascular area. The presence of two or more of these four criteria yielded a sensitivity and specificity of 88% and 92% respectively.5 Based on ACR criteria, our patient was diagnosed with GPA.

Once the diagnosis has been suspected clinically, several laboratory markers have been recognized to differentiate GPA from other forms of vasculitis. In 1985, ANCA were linked to GPA.6 Immunofluorescence patterns described in ANCA vasculitis were either diffuse within the cytoplasm (C-ANCA) or perinuclear (P-ANCA).7 Two relevant target antigens, proteinase 3 (PR3) and myeloperoxidase (MPO) located in the azurophilic granules of neutrophils and the peroxidase-positive lysosomes of monocytes were found in ANCA vasculitis. Antibodies that target PR3 and MPO antigens are called PR3-ANCA and MPO-ANCA, respectively.

Patients with a clinical picture suggestive of GPA are three times more likely to have a C-ANCA, rather than a P-ANCA. Stone et al. determined that the sensitivity of ANCA is only 60%; however, the specificity can be quoted up to 99% (if both ELISA and immunofluorescence testing are done). Further, in GPA, 80–90% of patients are PR3 positive, compared with only 10–20% MPO positive. The presence of positive-PR3 antibodies was later determined to have prognostic value in treating patients with GPA.8 In disease limited mostly to upper respiratory airways, ANCA may be negative in up to 40% of cases. That will make diagnosis even more challenging.

GPA can also affect the kidneys in up to 80% of cases, especially during the first two years of the disease.3 Detecting renal involvement early is difficult, but essential. New avenues were opened by a study of Ohlsson et al. that assessed the use of urinary biomarkers, such as cytokines (IL-6, IL-8) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1). This study demonstrated that MCP-1 levels in urine were significantly higher in ANCA-vasculitis patients (in the stable phase of the disease) compared with healthy controls. Further, patients with higher urinary levels of MCP-1 and IL-6 tend to relapse more within three months and have poor prognoses.9 In 2012, a study by Lieberthal et al. determined that increased urinary MCP-1 concentrations were able to discriminate between active renal disease and remission. It was noted that a 1.3-fold increase in MCP-1 had 94% sensitivity and 89% specificity for active renal disease.10 Thus, in addition to conventional markers of disease activity, such as CRP, ANCA and vasculitis activity scores, urinary MCP-1 can be a promising prognostic marker.

We would also like to emphasize the role of biopsy to establish a clear diagnosis. Most often, skin and renal biopsies are obtained in patients to diagnose ANCA vasculitis. Nasal biopsy is rarely performed due to fear of nonspecific results, but these may be valuable to rule out other non-inflammatory causes, infections and malignancy. Typical findings are chronic inflammation and capillaritis, but granulomatous features are diagnostic for GPA, especially in patients with limited disease and negative ANCA. Borner et al. showed that the sensitivity of sinonasal mucosal biopsy in localized disease was about 53% compared with C-ANCA antibodies of 47%.11

As previously mentioned, our patient had nasal biopsy-proven disease that showed both granulomatous changes and neutrophilic infiltration of the intima of the small blood vessels.

Once the diagnosis has been confirmed and disease activity analyzed, treatment is initiated. The use of cyclophosphamide and rituximab, in addition to glucocorticoids, changed the fate of these diseases from fatal to chronic conditions. The treatment is a two-phase approach: induction and maintenance. The induction phase includes a combination of high-dose glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants (either cyclophosphamide or rituximab). However, in the recent years, rituximab was shown not to be inferior to cyclophosphamide and has been favored because it seems to have favorable outcomes in disease remission.12

Several studies have shown that rituximab may be superior to cyclophosphamide under some circumstances. Rituximab has also been shown to be superior to cyclophosphamide to achieve immunosuppression in patients with PR3-positive ANCA-vasculitis.13 Analysis from the RAVE and RITUXVAS trials have suggested that rituximab may be more effective than cyclophosphamide in refractory disease.12

Once remission is achieved, the patient can be transitioned to maintenance therapy with azathioprine or methotrexate. A recent study showed that patients treated with a low dose of rituximab had a lower relapse rate at 28 months compared with patients treated with azathioprine.14 Glucocorticoids have been shown to decrease disease relapse at six months and, currently, several studies are underway to establish formal glucocorticoid guidelines.15 After remission has been achieved, patients need to be monitored closely to assess for relapsing disease.

Just recently, Rhee et al. showed that persistent hematuria (but not proteinuria), after induction therapy, was associated with a four times higher risk of disease relapse.16 In ANCA vasculitis, the risks of relapsing disease continue to remain a major concern in the disease process. The risk factors for relapsing disease include the diagnosis of GPA, previous relapse and positive PR3-antibodies.12 In a small study, a CTLA4-Ig inhibitor drug (abatacept) that affects T cell activation, was proposed for treatment of non-severe relapsing GPA disease. Of the 20 patients included in the study, 90% had disease improvement, and 80% achieved remission. Many of these patients were able to rapidly discontinue prednisone.17

In patients with severe disease, such as rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis and/or alveolar hemorrhage, plasma exchange has been proposed in combination with other remission induction agents.18

Conclusion

Increasing awareness and the ability to early recognize, diagnose and treat GPA will save a patient’s life. In the past 20 years, major advances in treatment have been made that dramatically improved long-term survival and quality of life for these patients.

Diana Girnita, MD, PhD, is an attending rheumatologist and faculty for the internal medicine residency program at Trihealth Good Samaritan Hospital in Cincinnati.

Diana Girnita, MD, PhD, is an attending rheumatologist and faculty for the internal medicine residency program at Trihealth Good Samaritan Hospital in Cincinnati.

Vishnuteja Devalla, MD, is an internal medicine resident at Trihealth Good Samaritan Hospital in Cincinnati, with an interest in rheumatology.

Vishnuteja Devalla, MD, is an internal medicine resident at Trihealth Good Samaritan Hospital in Cincinnati, with an interest in rheumatology.

References

- Friedmann I. McBride and the midfacial granuloma syndrome. (The second ‘McBride Lecture,’ Edinburgh, 1980). J Laryngol Otol. 1982 Jan;96(1):1–23.

- Mohammad AJ, Jacobsson LTH, Westman KWA, et al. Incidence and survival rates in Wegener’s granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis, Churg-Strauss syndrome and polyarteritis nodosa. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009 Dec;48(12):1560-1565.

- Mansi IA, Opran A, Rosner F. ANCA-associated small-vessel vasculitis. Am Fam Physician. 2002 Apr 15;65(8):1615–1620.

- Pagnoux C, Carette S, Khalidi NA, et al. Comparability of patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis enrolled in clinical trials or in observational cohorts. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015 Mar–Apr;33(2 Suppl 89):S77–S83.

- Fries JF, Hunder GG, Bloch DA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of vasculitis. Summary. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(8):1135–1136.

- van der Woude FJ, Rasmussen N, Lobatto S, et al. Autoantibodies against neutrophils and monocytes: Tool for diagnosis and marker of disease activity in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Lancet. 1985 Feb 23;1(8426):425–429.

- Niles JL, Pan GL, Collins AB, et al. Antigen-specific radioimmunoassays for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in the diagnosis of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1991 Jul;2(1):27–36.

- Stone JH, Talor M, Stebbing J, et al. Test characteristics of immunofluorescence and ELISA tests in 856 consecutive patients with possible ANCA-associated conditions. Arthritis Care Res. 2000 Dec;13(6):424–434.

- Ohlsson S, Bakoush O, Tencer J, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 is a prognostic marker in ANCA-associated small vessel vasculitis. Mediators Inflamm. 2009;2009:584916.

- Lieberthal JG, Cuthbertson D, Carette S, et al. Urinary biomarkers in relapsing antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. J Rheumatol. 2013;40(5):674–683.

- Borner U, Landis BN, Banz Y, et al. Diagnostic value of biopsies in identifying cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-negative localized Wegener’s granulomatosis presenting primarily with sinonasal disease. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012 Nov–Dec;26(6):475–480.

- Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul;363(3):221–232.

- Unizony S, Villarreal M, Miloslavsky EM, et al. Clinical outcomes of treatment of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis based on ANCA type. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Jun;75(6):1166–1169.

- Guillevin L, Pagnoux C, Karras A, et al. Rituximab versus azathioprine for maintenance in ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2014 Nov 6;371(19):1771–1780.

- Krischer J. The assessment of prednisone in remission trial (TAPIR)—Patient centric approach. ClinicalTrials.gov.

- Rhee RL, Davis JC, Ding L, et al. The utility of urinalysis in determining the risk of renal relapse in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018 Feb 7;13(2):251–257.

- Langford CA, Monach PA, Specks U, et al. An open-label trial of abatacept (CTLA4-IG) in non-severe relapsing granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s). Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Jul;73(7):1376–1379.

- Jayne DRW, Gaskin G, Rasmussen N, et al. Randomized trial of plasma exchange or high-dosage methylprednisolone as adjunctive therapy for severe renal vasculitis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007 Jul;18(7):2180–2188.