Discussion

PPD is the most common and most well-known component of hair dyes.1 It was first described by August Hofmann in 1863, and it was formulated at the end of the 19th century for use in hair dyes.2,3 It is favored in hair products due to its long-lasting character and the natural-appearing color imparted to the hair. PPD requires a secondary ingredient, such as a developer or oxidizer, to produce a black color. When exposed to the epidermis or dermis, PPD is oxidized to an allergenic hapten.

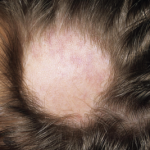

The ingredients in hair dyes are generally thought to have low to moderate acute toxicity, such as allergic contact dermatitis. Contact allergy to PPD can manifest as acute, subacute or chronic dermatitis. Studies involving dermatitis patients show the median prevalence of positive PPD patch test to be 6.2% in North America, 4% in Europe and 4.3% in Asia.4,5 Higher concentrations of PPD are present in darker shades of hair dye products.6 The frequency of induction of contact allergy to PPD by black henna tattooing is estimated to be 2.5% per application. Epicutaneous patch testing is the gold standard test to confirm hair dye contact allergy.

Environmental factors, including microbial agents, vaccines, diet, drug exposure, heavy metals and ultraviolet radiation, are believed to be involved in the pathogenesis of inflammatory arthritis in patients with a genetic susceptibility.7,8 Cigarette smoking is an example of a non-infectious environmental agent associated with the development of rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune thyroiditis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC).9,10 Silica exposure has been linked to scleroderma, RA, vasculitis and SLE.11 Certain solvents, such as trichloroethylene, mineral spirits and petroleum-based products, have been linked to scleroderma and other connective tissue diseases. Hair dyes have previously been suggested as a possible environmental trigger in the development of autoimmune inflammatory syndromes, including SLE, PBC and RA, but few studies address these compounds specifically.12-15

The development of autoimmune disease following exposure to environmental triggers is postulated to occur through various immunologic mechanisms, such as the alteration of autoantigen structure, altered expression of antigens, stimulatory effects on the immune system, T cell dysregulation, apoptosis-mediated autoimmunity, molecular mimicry and immunological cross-reactivity. These ultimately result in increased production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 10 (IL-10) and TGF-β, and immune complex formation.16,17

Rubin et al. studied the immune responses in mice repeatedly exposed to PPDs.18 The study revealed increased cellular infiltration after multiple exposures, with the inflammatory response peaking after four weeks. Flow cytometry demonstrated increased proliferation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the mice.18 A second series of analyses was conducted with hair dyes (as opposed to PPD alone), which produced similar results, with the exception of a higher increase in regulatory T cells (Tregs) than was seen in PPD use alone.18 Thus, hair dye use can induce a proinflammatory immune response, as well as possibly influence the autoantibody profile.

An early case study by Freni-Titulaer et al. indicates a positive association between the use of hair dyes and autoimmune inflammatory syndromes.19 However, a larger study carried out by Petri and Allbritton involving 218 SLE patients from the Hopkins Lupus Cohort found no significant relationship between hair dye use and the development of SLE.20 This study asked the participants to fill out a questionnaire on hair product use.

More recently, Cooper et al. found permanent hair dye use was associated with a small increase in the risk of developing SLE, especially with dark-colored dyes.21 The study examined the association between smoking and hair treatments (e.g., dyes, permanents) and the risk of developing SLE. Two hundred and sixty-five patients were recruited from rheumatology practices, and data were collected by 60-minute, in-person interviews analyzing the experiences that occurred before diagnosis. The study showed a small risk for developing SLE with use of permanent hair dyes (odds ratio [OR] 1.5; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.0–2.2) and with longer duration of use (OR 1.7; 95% CI 1.0–2.7; for six or more years) compared with non-dye users. The study did not show any association with smoking history and risk of developing SLE.

According to a study conducted in Sweden (1980–95), using hair dyes for more than 20 years damaged the immune system, increasing the likelihood of RA developing (exposed cases/referents 17/10; OR 1.9; 95% CI 0.8–4.5).14

In summary, we describe a patient who developed an inflammatory arthritis with concomitant use of hair dye. The timing and history of hair dye exposure was fundamental for the diagnosis. In patients where an association between use of hair dye and inflammatory disease is made, treatment goals include improving symptoms and increasing functional activity. Withdrawal of the causative hair dye was the mainstay treatment for our patient and is essential for all patients where this is suspected. In addition, physical therapy and NSAIDs can be used for the inflammatory joint pain. Anti-rheumatic therapy may be considered if the joint inflammation does not resolve when the offending agent is eliminated. Treatment with a potent topical corticosteroid or short course of oral corticosteroids may be required if there is concomitant skin involvement.

We recommend that manufacturers of hair dye products consider keeping the PPD concentration to the lowest possible amount to achieve the desired results. Restriction to PPD-free hair dyes and vegetable-based hair dye may be the safest solution for those exhibiting PPD sensitization. Hair stylists should be advised to use gloves while applying hair dyes to prevent contact with hands. Reading the ingredient list is imperative, especially if a hypersensitivity or immunologic reaction is suspected.